WASHINGTON — From ancient Greece to the American Confederacy, famous and powerful figures have been immortalized through plaster masks sculpted during a person’s life or immediately after their death.

In some cases, these haunting images served as the foundations for grand monuments. In others, the masks were maintained by families or museums as a kind of souvenir when an important person died.

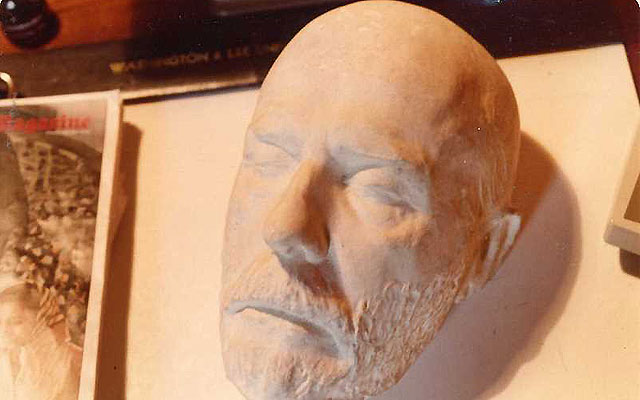

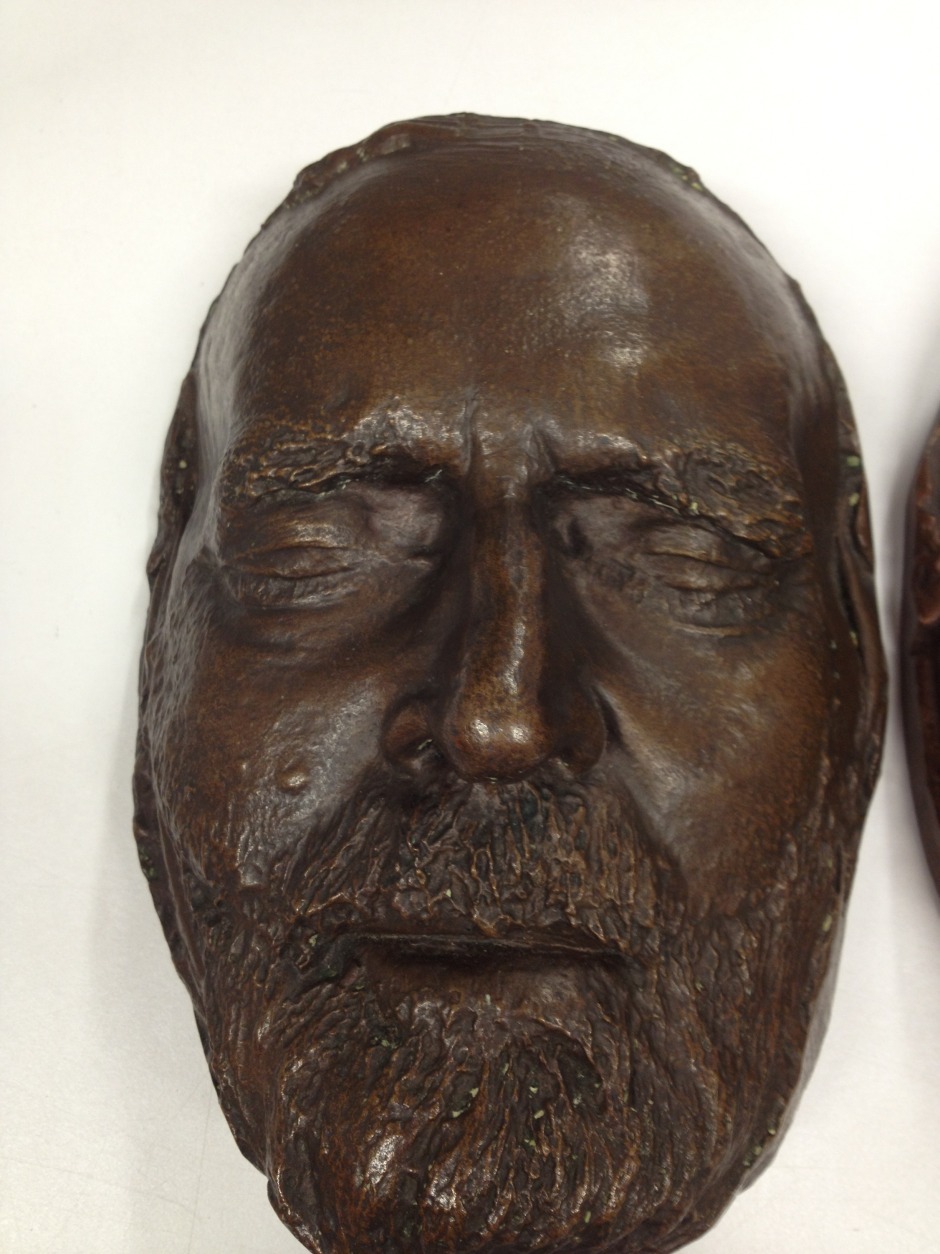

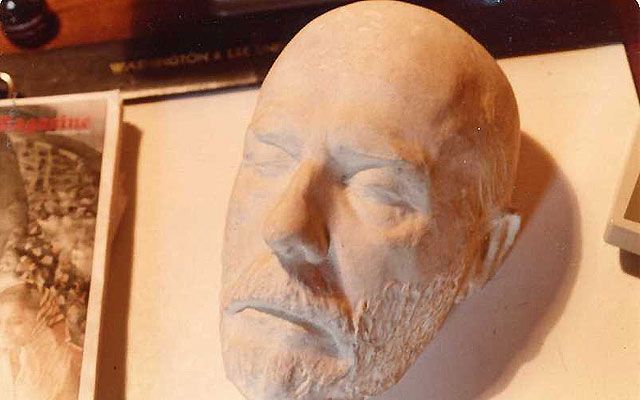

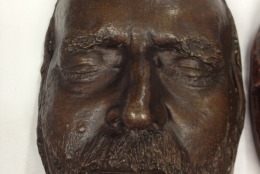

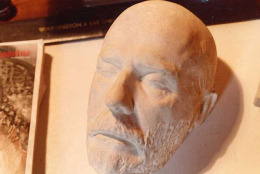

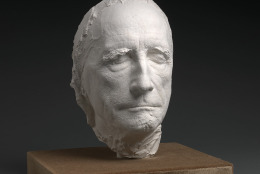

At the National Portrait Gallery, in Northwest D.C., the death masks of generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee sit side by side at the “One Life: Grant and Lee” exhibit, on display through May 31, 2015. The two generals, fierce rivals in life, now rival each other in death, thanks to the stark difference in their masks.

Lee appears serene and relaxed — before dying, he was in a coma for several weeks following a stroke. Grant, on the other hand, is clenching his face in apparent pain. The former president died from throat and mouth cancer.

“In the mid-19th century, particularly in Anglo-America, there is a fascination and even comfort with death,” says David Ward, senior historian at the National Portrait Gallery and curator of the “One Life” exhibit. “The whole process was a lot more public than it is now.”

Death and life masks were routinely taken as a way to honor prominent members of society. The practice dates back to ancient Greece and Egypt, when these masks were commissioned by powerful families and used as relics and remembrances or in rituals.

In the United States, masks became a popular way to better preserve the likeness of an important person. Molds were more accurate than paintings in the days before photography, Ward says.

“There was an element of posterity,” he says. “You have to remember — this is still a period of intense spiritualism. There is a sense of the spirit world, of leaving the body behind.”

Yet the practice started to shift away from masks, and not only because of the advent of cameras.

Protestantism “privatized” the mourning process, Ward says. Suddenly, it became unseemly to take the likeness of a person mere minutes after they died. But time was key to creating a truly accurate death mask. Artists could not wait too long after a person died because decomposition and decay would alter their facial features. It was paramount to capture their likeness and even create a lifelike sculpture for future use.

Lee’s mask was used as the basis for his memorial at Washington and Lee University. He commissioned the death mask during his life while he was president of the college. It is now part of a larger, full-body sculpture now on display in the school’s chapel.

But while death masks were common practice, Ward says Lee’s memorial stands out among the general’s contemporaries.

“Lee, much more so than Grant, is a mystical figure because he embodies the South. He’s seen as the perfect Southerner,” Ward says. “He’s not really implicated in slavery.”

His tomb recalls a more ancient practice of memorializing the dead.

“It looks like a crusader’s tomb, or the tomb of a French king,” Ward says. “It was incredibly detailed in a way no one was doing, and that’s because Lee was essentially a god to the South.”

But Grant’s legacy is much more murky, Ward says. His administration was rumored to be corrupt, and his Reconstruction efforts following the Civil War were largely unsuccessful. Even his death mask shows a kind of anguish absent from Lee’s.

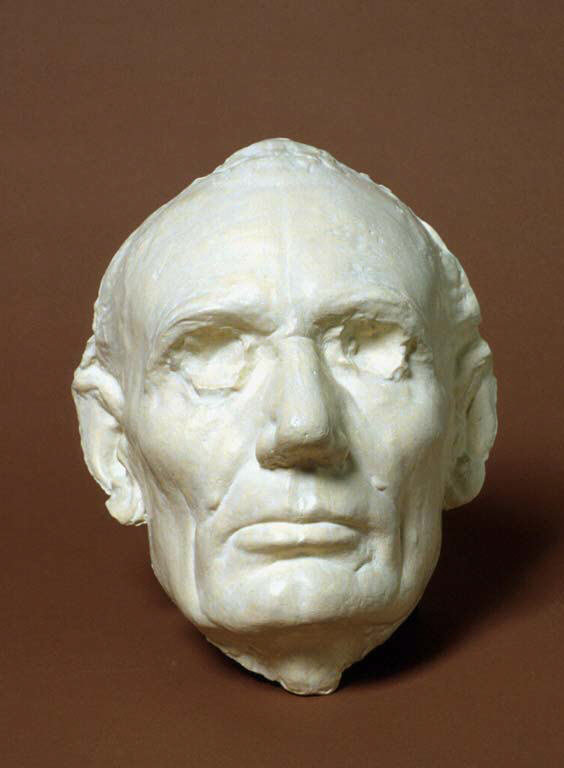

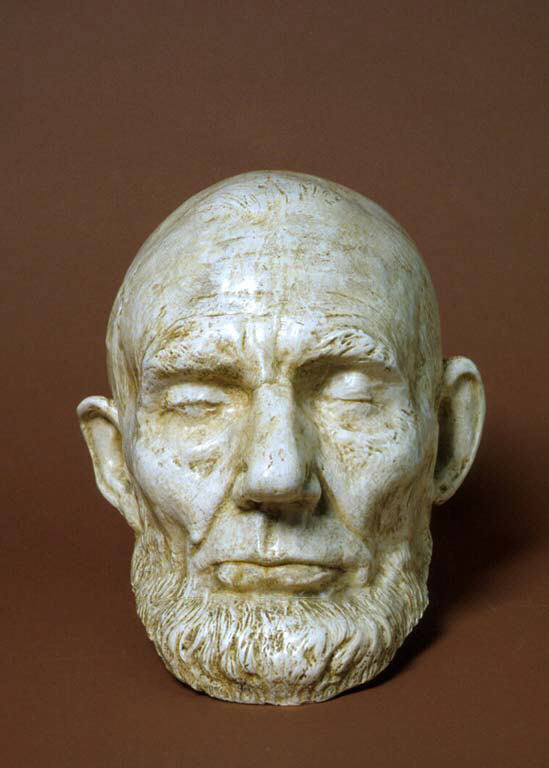

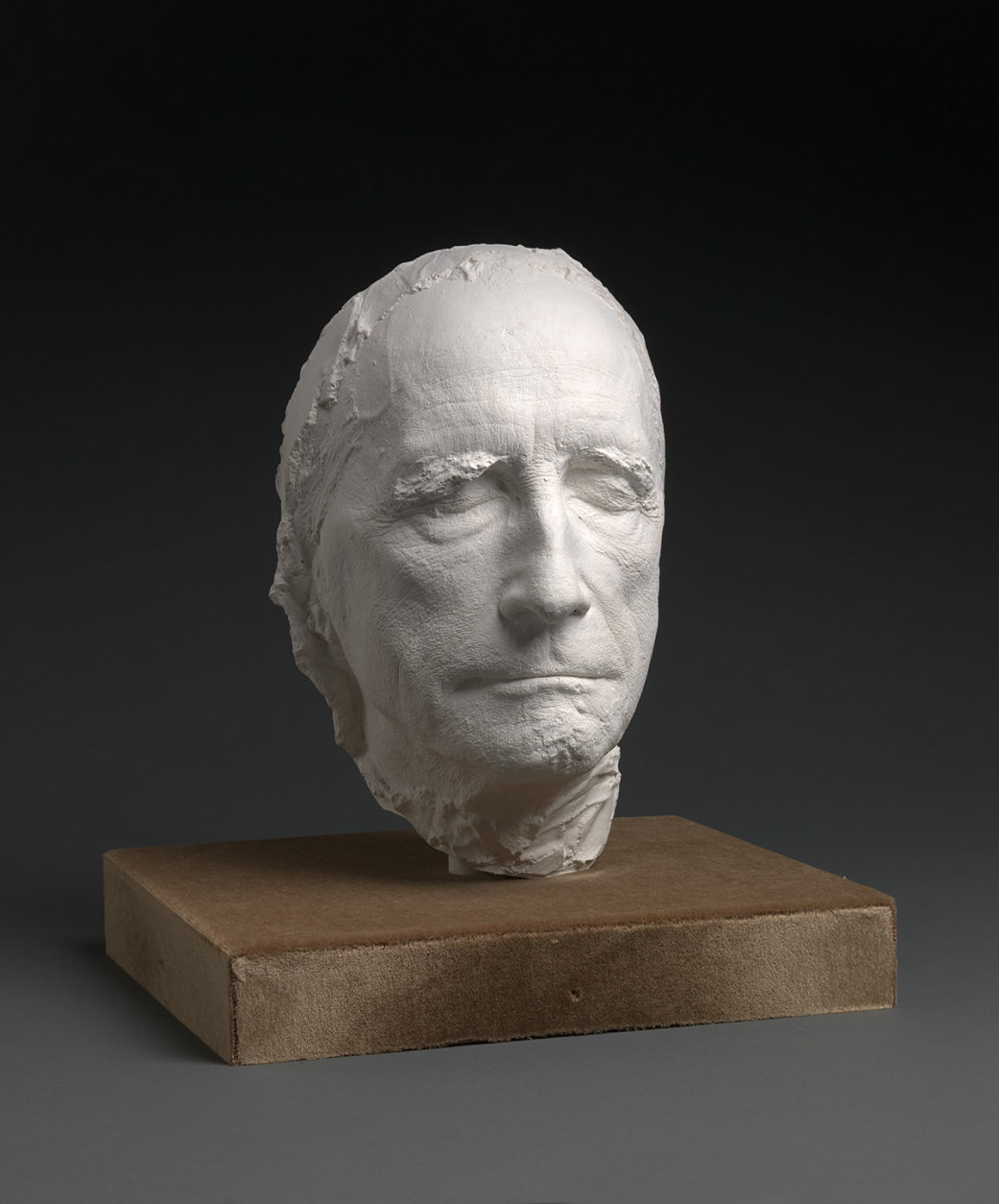

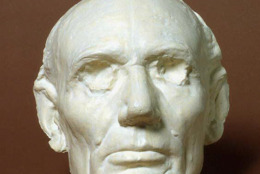

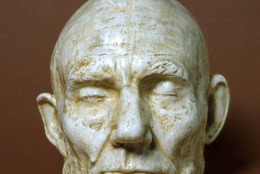

Upstairs at the Abraham Lincoln exhibit, two of the former president’s life masks sit side by side. One was cast in 1860 by Leonard Wells Volk. A second mold was taken just five years later by Clark Mills. The difference is unsettling. Lincoln is weathered and wrinkled in the latter, while his face is mostly smooth in the former. The toll of his presidency is present.

“There was an intense interest in phrenology and the way the character comes through a person’s features,” says Dorothy Moss, curator of painting and sculpture at the National Portrait Gallery.

The process of mask-making was painstaking. Subjects had to sit uncomfortably for several hours with a heavy plaster over their face. Straws were inserted into the nostrils to allow for breathing; smiling and moving were discouraged.

Thomas Jefferson endured a near-death experience during his sitting, Ward says. The artist John Henri Isaac Browere, who captured the likeness of several prominent Americans in the 19th century, was distracted and left the plaster on too long. The elderly Jefferson, ever the gentleman, was too polite to tell Browere that he was having difficulty breathing. Jefferson’s daughters later accused Browere of trying to kill the president, Ward says.

“It was not particularly funny,” he adds.

President Washington, on the other hand, famously tried to make light of his sitting by cracking a smile when his wife walked in the room. That mask, like hundreds of others, didn’t survive through history.

But the practice did.

French-American painter and sculptor Marcel Duchamp created his own life mask, which is archived in the National Portrait Gallery.

And contemporary artist Karin Sander uses modern technology to cast her molds. Instead of using heavy plaster, she scans the human body and creates life-sized, three- dimensional images of her subjects.

“There’s something that the three-dimensionality captures that a photograph can never capture,” Moss says.

Follow @WTOP and WTOP Entertainment on Twitter and WTOP on Facebook.