BY TOM COYNE

ASSOCIATED PRESS

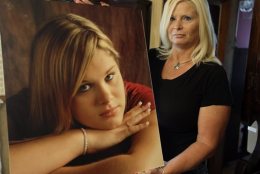

When her 19-year-old daughter died of injuries sustained in a Mother’s Day car crash five years ago, Lisa Moore sought comfort from the teenager’s cellphone.

She would call daughter Alexis’ phone number to listen to her greeting. Sometimes she’d leave a message, telling her daughter how much she loved her.

“Just because I got to hear her voice, I’m thinking `I heard her.’ It was like we had a conversation. That sounds crazy. It was like we had a conversation and I was OK,” the Terre Haute, Ind., resident said.

Moore and her husband, Tom, have spent $1,700 over the past five years to keep their daughter’s cellphone service so they could preserve her voice. But now they’re grieving again because the voice that provided solace has been silenced as part of a Sprint upgrade.

“I just relived this all over again because this part of me was just ripped out again. It’s gone. Just like I’ll never ever see her again, I’ll never ever hear her voice on the telephone again,” said Lisa Moore, who discovered the deletion when she called the number after dreaming her daughter was alive in a hospital.

Technology has given families like the Moores a way to hear their loved ones’ voices long after they’ve passed, providing them some solace during the grieving process. But like they and so many others have suddenly learned, the voices aren’t saved forever. Many people have discovered the voices unwittingly erased as part of a routine service upgrade to voice mail services.

Often, the shock comes suddenly: One day they dial in, and the voice is inexplicably gone.

A Sprint upgrade cost Angela Rivera a treasured voice mail greeting from her husband, Maj. Eduardo Caraveo, one of 13 people killed during the Fort Hood shootings in Texas in 2009. She said she had paid to keep the phone so she could continue to hear her husband’s voice and so her son, John Paul, who was 2 at the time of the shooting, could someday know his father’s voice.

“Now he will never hear his dad’s voice,” she said.

Jennifer Colandrea of Beacon, N.Y., complained to the Federal Communication Commission after she lost more than a half dozen voice mails from her dead mother while inquiring about a change to her Verizon plan. Those included a message congratulating her daughter on giving birth to a baby girl and some funny messages she had saved for more than four years for sentimental reasons.

“She did not like being videotaped. She did not like being photographed,” Colandrea said of her mother. “I have very little to hold onto.

“My daughter will never hear her voice now.”

Transferring voice mails from cellphones to computers can be done but is often a complicated process that requires special software or more advanced computer skills. People often assume the voice mail lives on the phone when in fact it lives in the carrier’s server. Verizon Wireless spokesman Paul Macchia said the company has a deal with CBW Productions that allows customers to save greetings or voice mails to CD, cassette, or MP3.

Many of those who’ve lost access to loved ones’ greetings never tried to transfer the messages because they were assured they would continue to exist so long as the accounts were current. Others have fallen victim to carrier policies that delete messages after 30 days unless they’re saved again.

That’s what happened to Rob Lohry of Marysville, Wash., who saved a message from his mother, Patricia, in the summer of 2010. She died of cancer four months after leaving a message asking him to pay a weekend visit to her in Portland, Ore.

“I saved it. I’m not sure why I did, because I typically don’t save messages,” Lohry said.

The message was the only recording Lohry had of his mother’s voice because the family never had a video camera when he was growing up. He called the line regularly for a year because he found it reassuring to hear her voice. But he called less often as time passed, not realizing that T-Mobile USA would erase it if he failed to re-save the message every 30 days.

“I always thought, `At least I know it’s there,'” he said. “Now I have nothing. I have pictures. But it’s something where the age we live in we should be able to save a quick five-second message in a voice mail.”

Dr. Holly Prigerson, director of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s Center for Psychosocial Epidemiology and Outcomes Research and a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School who has studied grief, said voice recordings can help people deal with their losses.

“The main issue of grief and bereavement is this thing that you love you lost a connection to,” she said. “You can’t have that connection with someone you love. You pine and crave it,” she said.

Losing the voice recording can cause feelings of grief to resurface, she said.

“It’s like ripping open that psychological wound again emotionally by feeling that the loss is fresh and still hurts,” Prigerson said.

But technology is devoid of human emotion.

In the Moores’ case, Sprint spokeswoman Roni Singleton said the company began notifying customers in October 2012 that it would be moving voice mail users to a different platform. People would hear a recorded message when they accessed their voice mail telling them of the move. Sprint sent another message after the change took effect.

No one in the Moore family got the message because Alexis’ damaged phone was stored in a safe.

Singleton said the company tried to make sure all of its employees understand the details of its services and policies, “but mistakes sometimes happen. We regret if any customers have been misinformed about the upgrade,” she said.

Lisa Moore finds it hard to believe Sprint can’t recover the message.

“I can’t believe in this day and age there’s nothing they can do for me,” she said.

—

Copyright 2013 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.