Hoai-Tran Bui, special to wtop.com

WASHINGTON – Lila Asher’s Chevy Chase, Md. house is filled with paintings, sculptures and prints that the 91-year-old artist created over nearly seven decades of work.

Asher’s art career traces back to the early 1940s, when she volunteered in The United Service Organizations’ Hospital Sketching Program. There, she drew portraits of immobile G.I.s.

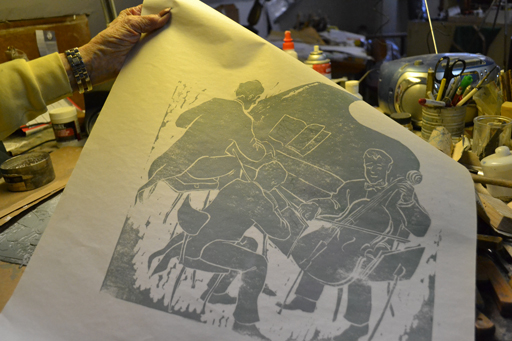

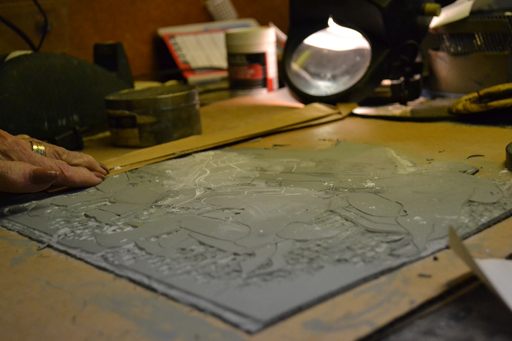

The Philadelphia native relocated to D.C. in 1946, where she established a studio for painting, sculpture and prints, and explored a career as both an artist and art professor at Howard University. Asher officially retired in 1991, but has continued to produce paintings and art prints from her studio at home.

This year, Asher has been chosen as one of the featured artists in Art Cart: Saving the Legacy, which preserves the works of aging artists and connects them with younger art students.

The project was started by Columbia University students in New York and is expanding to national levels this year. D.C. is one of the first cities to welcome the program.

How long have you been painting and doing art prints?

Oh I got my first oil paints on my seventh birthday. My parents knew I was interested in drawing. Then I went to a children’s class at what later became the University of the Arts. I grew up in Philadelphia. Then I studied painting with Frank Linton, who was a pupil of Thomas Eakins, and then went to college at the University of the Arts.

I know you mostly do art prints now, but what other styles do you do?

I do portraits. I also do some stained glass.

In terms of portraits, I saw in your bio that you did charcoal sketches of members of the U.S. armed forces. Can you tell me about that?

I was officially a one-woman USO camp show. I would travel by myself six days at a time at one hospital, then would travel Sunday to the next hospital. (I did) military hospitals mostly — in Philadelphia, it was a Navy hospital.

And this was during World War II?

Yes. And literally, I sat from bed to bed. I sat on a bed with a young man and did a sketch.

How was that experience?

Well it was a wonderful experience and very interesting too, because the young men — some of them knew nothing about art. I had one guy say to me after I had finished, “Is that a freehand drawing?” And I had another guy say to me, “I don’t take nothing for nothing,” and handed me 50 cents. And so I was quite embarrassed, but I thought quickly.

I said, “Well if you want to give me something, I’ll collect your shoulder patches and have an insignia from all the different areas.” And so that began a collection of shoulder patches, which I made into a little quilt.

And do you still have that quilt today?

Yes — it’s in my book. I wrote a book called “Men I Have Met in Bed.”

When did you start doing charcoal portraits of the soldiers?

Actually, I started when I was in college. The Stagedoor Canteen was only two blocks from college, and they called the college to see if there was a student who would be willing to come and sketch. The dean called me in to ask me to go. I was very flattered, so I went a few nights a week when I was still in college.

There also were some older artists in the area who I met and who organized a couple of artists at the time to go to local hospitals. We went to Atlantic City, where they had taken over a number of the fine hotels as hospitals. And also we went to Valleyford, where they had another hospital.

Finally the USO realized that this was important. Not only did the guys enjoy having their pictures sketched, but they had somebody to talk to for 30 minutes at a time. The guys were pretty lonely in the hospitals, so it was quite beneficial. We went only to those who were really bedridden, who couldn’t go to the song-and- dance things that were given in the auditorium.

And so the USO finally organized it very well. They had a center in New York, and I worked six days. I had a little form with name, rank and serial number. And also, the name and address to where the patient wanted the picture sent. At the end of the six days, I had this little card attached to each one and I would give it to the special services officer at the hospital.

He would package the whole thing and send it back to New York. And then New York would send each (picture) in a tube to the recipient that the patient mentioned.

You said these men were bedridden. Did they have any injuries that were particularly disturbing to see?

Oh yes. And of course, there were hospitals where there were bones broken — they were covered in splints and plaster casts in all sorts of directions. And when I first came in, it was difficult. But it was almost comical to see the strange directions of arms or legs.

Are these the kind of experiences that inspire your art?

Years ago I had a show. One reviewer said, “It’s obvious that Mrs. Asher is mostly interested in human relations.” And I thought, “Why does he say that?” And I went around and looked at my prints, and it very obvious. I do mostly people and people involved in human relations — also some biblical subjects and some mythological subjects. Those are very nice because everyone knows what they’re about.

Do you approach art differently now that you’ve retired?

I don’t think I approach it any differently, it’s just that I can do it when I feel like it. And some days I work very hard, and some days I have other commitments, and so it’s kind of uneven, but I do it all the time one way or another.

Do you do most of your work now at home?

There’s a studio on the third floor where I do most of my work. It keeps me young. The studio is why I bought the house. I needed a place big enough for the children and also big enough for a studio. And when I first moved here I thought it was a wonderful, big place. As the years went by, it got smaller and smaller. So now I’ve got some of the work downstairs in the basement.

How long ago did you move here?

It was over 50 years ago in 1955.

And you’ve been doing art all this time. What is it about art that keeps you doing it for so long?

It’s what I do. I sort of don’t know anything else. It’s what I want to do and what I’ve been doing. I taught at Howard University for over 43 years. And it’s just sort of my life. I wouldn’t know how to go on without it.

Follow @WTOPLiving on Twitter.