Heather Brady, wtop.com

WASHINGTON – Ten years ago, Washington Ballet artistic director Septime Webre married his fascination with Prokofiev’s Cinderella, a musical score with sweeping, sumptuous waltzes and comedic interludes, with the skilled work of his dance company.

Webre performed in a production of “Cinderella” when he was a student, so it isn’t surprising that he breathed life into a Washington Ballet version of the archetypal story. Webre started showing the ballet every five years, and will bring it back to the stage at the Kennedy Center March 21-24 in the company’s third performance.

The ballet offers a chance for company dancers in the original 2003 production to tackle principal roles while also providing opportunities for younger students in the company to appear in “Cinderella” for the first time.

WTOP Living caught up with Webre ahead of the show’s debut to talk about the story behind the ballet and what he loves about it.

What keeps “Cinderella” timely and relevant?

It’s one of the grand fairy tales that is really a story about good and evil, redemption and love. These compelling themes exist in Greek myths and fairy tales from all around the world, and they continue to be compelling to us because they tell us something about our humanity. That’s one of the reasons why Cinderella keeps returning to the repertoire.

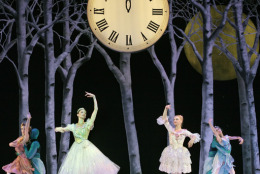

The other reason is the music and the dancing is just a heck of a lot of fun. You know, it’s just great music, and the dancing is challenging to the artists. The (ballet) is set in France in the 18th century and the ballroom of act II is in the Hall of Mirrors at the palace of Versailles. There are huge tier mirrors that tilt forward to the audience as the dancers whirl about in a sea of taffeta. There’s this strong French element, although the fairies who appear and help Cinderella prepare for the ball are based on early 20th century fairies drawn in an art nouveau kind of style.

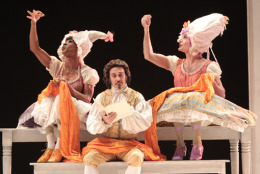

I read that sometimes the stepsisters are played by men. Is that the case in The Washington Ballet’s version?

They are played by men. It’s in the kind of British musical tradition (of the) late 19th, early 20th century musical, (which) had men in travesty roles. So these stepsisters are truly ugly.

When the fairies of the seasons — spring, summer, fall and winter — help the fairy godmother prepare Cinderella for the ball perform their solos, is that a moment for dancers to shine in terms of technical proficiency?

These are fiendishly difficult solos for women and also a very grand dance for the fairy godmother — a dance with four dragonflies who are played by adult men who lift her in the air. Her feet almost never touch the ground. So these are virtuosic displays that are visual fireworks in a way and speak to the power of magic and the joyful expression of being hopeful that one might meet someone.

When you choreograph for a large number of dancers, there is potential for on-stage traffic jams. Is that difficult to coordinate?

In both the garden scene and the waltzes at the ball, there are moments that resemble Grand Central Station at 5:15 p.m. With our studio company and some children’s roles, there are between 60 and 75 dancers in the production. In the studio I’m definitely like a traffic cop, you know, bullhorn in one hand and a whistle in the other.

When you were originally choreographing The Washington Ballet version, did you draw inspiration from other performances of “Cinderella” set to the same score?

(Frederick Ashton) made a clear, classic version for the Royal Ballet in the 1940s. It had a lot of British musical humor. I didn’t use any of his steps at all, but I was certainly influenced to some degree by that. For the courtiers in Act II, for example, for the fairies who accompany the fairy godmother and this coterie of magical garden creatures that come with the fairy godmother to help Cinderella transform for the ball, I was influenced by really wonderful speedy Balanchine technique, sort of the steps and spirit that you find in a Balanchine ballet, and also British musical humor, which is bawdy and fun.

When dancers are in the Hall of Mirrors, do the mirrors make things more difficult for the dancers?

Yeah, the mirrors can be a little discombobulating for the dancers. Traditionally in a rehearsal hall in the studio, the mirrors are at the front of the room, so the mirrors are in the studio where the audience is on stage. The mirror is your front, essentially. But in the case of this set design, the mirrors are at the back, facing the audience. When your body is so used to facing the mirror, and suddenly you’re on stage and the lights are brightly in your face and the audience is so dark, I think some dancers get a little confused for a moment. It takes a little extra concentration to remember that the mirrors are actually behind you and not in front of you.

In terms of the ballet itself, what parts make you really happy as an artistic director?

I think the waltz melody that Prokofiev wrote for Act II is among the greatest waltzes ever written and certainly my favorite written in the 20th century. The score is from the early 1940s, and it’s beautiful. It harkens back to the waltzes of the 19th century, particularly some of the waltzes that Tchaikovsky wrote for Swan Lake, but it’s got a modernist feeling to it, so it feels crisp and new.

It’s exciting when the shoe fits, so I love that moment too, and just seeing the comedy of the stepsisters. I grew up in a family of eight brothers, and we still have this sophomoric sense of boy humor. I worked a lot of jokes into the stepsisters’ parts that just make me laugh. It