By ANGELA HARVE

Capital News Service

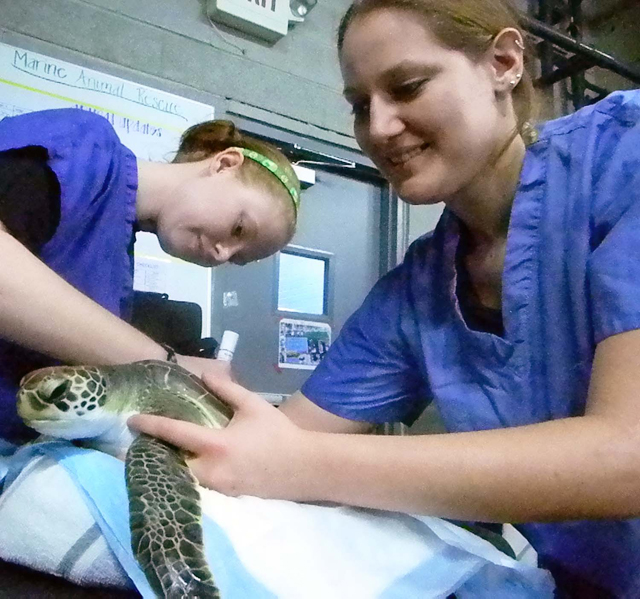

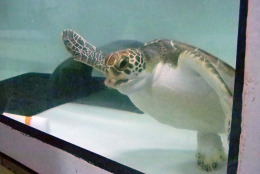

BALTIMORE – Sea turtle number 32 had a small part of its front left flipper amputated last week because a joint lesion has not healed since the reptile was brought to the National Aquarium’s Marine Animal Rescue Program in November.

“It’s an infection in the joint so we don’t want it to spread and then have to amputate the entire flipper,” said Amber White, a husbandry aide.

“As you can image that would impair his swimming ability.”

The surgery on Friday went well. Number 32 has stitches in the flipper and has resumed its normal swimming activities, while stitches on the turtle’s front right flipper are healing well after a similar amputation was done at the animal care center in January.

Number 32 was found stranded off the coast of Cape Cod, Mass., White said. Its rehabilitation carries high stakes because it is a Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle, the smallest and most critically endangered species of sea turtles.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has determined the Kemp’s Ridley turtle’s nesting numbers started declining dramatically after 1947, reaching a low of 702 nests in 1985.

Since the mid-1980s, the number of nests laid in a season has been increasing. There were 20,800 documented nest in 2011. This increase is attributed to nest protection efforts and regulations requiring the use of turtle excluder devices in commercial fishing trawls.

Sea turtles were in the public eye last week when more than 1,000 scientists, researchers, conservationists, lawmakers and students from 80 different countries came to Baltimore for the 33rd Annual Symposium on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation, said Dr. Ray Carthy, president of the International Sea Turtle Society and assistant unit leader of the Florida Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit.

The National Aquarium of Baltimore and the Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center cooperated on the symposium to bring attention to the critical issues affecting sea turtles and diamondback terrapins, the Maryland state reptile, in the Chesapeake Bay.

“The water quality and health of the Bay affects all of us because sea turtles are important sentinels of the ecosystem,” Carthy said.

“The Bay is an important foraging and nesting area for turtles, as well as an important developmental area for young turtles.”

The injuries turtles endure as a result of many of the issues discussed at the symposium can be seen at the aquarium’s rescue program. It has treated and released turtles and other marine animals stranded in Maryland for 21 years. It also is a part of a regional stranding network, so it can take the overflow from other animal care centers from Maine to Virginia, said Jennifer Dittmar, the stranding coordinator.

The animal care center has seven juvenile turtles in its care: two loggerheads, two greens, and three Kemps. All came to the program in November and December after being stranded in Cape Cod, White said.

The turtles are being treated for a variety of conditions such as cold stunning — the same as hypothermia in humans — respiratory infections and the exposure of shell bone, White said.

Rehabilitation time depends on the turtle’s condition, but typically lasts five to six months. During their stay the turtles’ energy levels and respiratory rates are closely monitored and program veterinarians perform surgeries, ultrasounds, endoscopies and other procedures as necessary, White said.

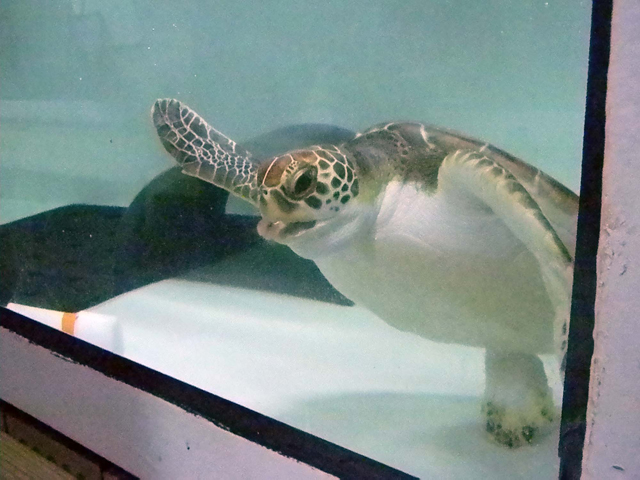

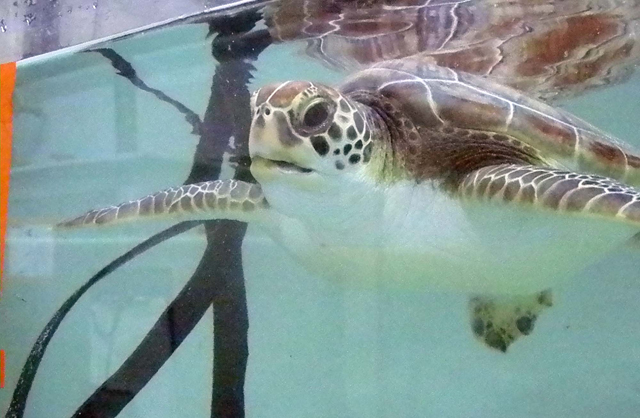

The staff tries to mimic the turtles’ natural environment as much as possible. Currents are created by the tank’s water system. To replicate sea kelp, car wash strips are attached to PVC pipes, and little tunnels were made for the turtles to hide under.

A number painted on the shell identifies each turtle. Their sex cannot be determined until they are a little older — males have longer tails. They have yet to be named, so White affectionately refers to the group as the brat pack, in tribute to classic 1980s movies.

Many of the staff and researchers from the National Aquarium and the program attended the symposium, where this year’s theme was connections. Carthy said Baltimore was the ideal location for international conservationists and scientists to meet with federal workers to share research and discuss protection and conservation policies.

“The sea turtle community is global, and many of the laws passed in the United States affect conservation efforts worldwide,” Carthy said.

“Having this event in Baltimore allows people in the sea turtle community to easily meet and exchange ideas with federal workers.”

The exchange continued with a teachers workshop, held at the National Aquarium and run by the Virginia Aquarium’s education department, that drew about 30 educators, most from Baltimore city and county areas. Educators were introduced to the lives of sea turtles in the Chesapeake Bay as they discussed how to educate students about the health of the estuary.

“We want to help educators incorporate sea turtles and conservation careers into their curriculum,” Carthy said, “and it’s personally important to me to target minorities that are underrepresented in the conservation fields.”

Artwork made by students from six Maryland schools was on display at the symposium as part of a contest with the theme of how humans can help sea turtles overcome threats they face.

In the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic Ocean sea turtles can face entanglement, cold stunning, bycatch, habitat denigration, and agricultural and industrial runoff causing dead zones, Carthy said.

These are some of the dangers number 32 will face when it is eventually released. After the surgery is complete, the program staff will wait for signs that it can hunt and forge and is healthy enough to return to the wild.

White said there will be a test.

“We drop in live crabs. It’s not easy prey, they fight back.”

(Copyright 2013 by Capital News Service. All Rights Reserved.)