Paul D. Shinkman, wtop.com

Tw: @ShinkmanWTOP

SOLOMONS ISLAND, Md. – Bay captain Pete Ide signals to the oncoming crab boat he’d like to parley.

It’s a sunny day on the Chesapeake Bay and boaters of all sorts are out conducting their business. Ide had been steering his charter boat with his feet while instinctively scanning for fish and eyeing the sonar.

Aboard the crabber are three watermen who look as comfortable on the water as the crabs they haul onboard. The boat slows down along the route of their trap buoys.

“This guy here’s a reporter from Washington, D.C.” Ide calls out, and admits to them he’s about to ask a “stupid” question. “You seen any sharks?”

If similar conversations with other watermen that day were any indicator, these young men would deliver blank stares, then talk about the rare shark they heard someone else talk about that one time in ’87. Or was it 2010?

“Oh yeah! We just got bites out of the crab pots, man. No bull****,” said Kelly Sullivan, based out of Middle River just east of Baltimore.

Sullivan went on to describe how his crew and he had been pulling pots up all month with massive, foot-wide bite marks that caved in the metal cages’ corners. Sullivan, wearing loose-fitting waterproof coveralls, surmised the perpetrator was a bull shark scavenging for either the fish bait, or the crabs they lured.

“We definitely thought about going shark fishing tomorrow,” he says.

Check out the gallery at right for a full tour of sharks in the Chesapeake.

Unlike the nearby ocean coasts, the bay is not a hotbed for shark sport fishing, largely due to the low numbers of sharks that can exist in the water. Bull sharks are among the only species that can withstand salinity levels that low.

Ide, who runs Captain Pete’s Charter Fishing out of Solomons Island, says that during hot summers, like in 2012, fishermen observing large schools of fish will see “something big dashing through them.”

He recounts the 8.5-foot bull shark caught near the Bay Bridge in 1987, when he was a young man starting his commercial fishing career at Scheible’s Motel & Restaurant, a nearby Southern Maryland seafood stalwart.

That year witnessed a hotter summer than the five years before or after, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Biologist David Lowensteiner, from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, says scientists anticipate the warm winter and summer will have some effect on the behavior of marine species, but have no way of predicting specific changes.

Given the general prevalence of sharks in the bay, it’s unusual that there has never been a shark attack here or anywhere else in Maryland, he says.

“In some ways, I think it’s surprising it happens that infrequently,” says Lowensteiner, based on Solomons Island. “Bull sharks are a common visitor to the Chesapeake Bay.”

But unlike hotspots for shark attacks, such as Florida or California, Maryland has a short coastline and very few varieties of sharks, he says. The jellyfish that swarm the bay’s tidal waters during the summer also keep would-be swimmers out of the water, says Ide.

Lowensteiner says a bite mark like the ones Sullivan described on his crab pots are likely from a bull shark, which would be upward of 8 feet long.

“That’s a large shark,” he says, adding there aren’t other species he could think of that would be able to inflict similar damage.

Most watermen catch sharks by accident in their commonly employed “pound nets.” Ide says this is how area local Willy Dean came across his 8-foot specimen in 2010.

Pound nets cash in on the instinct of fish to swim away from the shore when they come across an obstruction. Watermen set poles in the river bottom to feed a fence of net out from the coast. Fish that run into that wall will swim away toward open water, where they come across a second net shaped like a heart. This funnels fish into a trap, called the pound, and prevents them from escaping.

These nets are unregulated, says Lowensteiner, and are rarely documented or have warning lights. This creates a hazard for unwitting boaters and often becomes a snare for sharks.

“Every big shark I’ve known to have been caught on this part of the Chesapeake Bay has come out of the pound net,” says Ide. “It’s very unlikely you would catch one with a hook and line.”

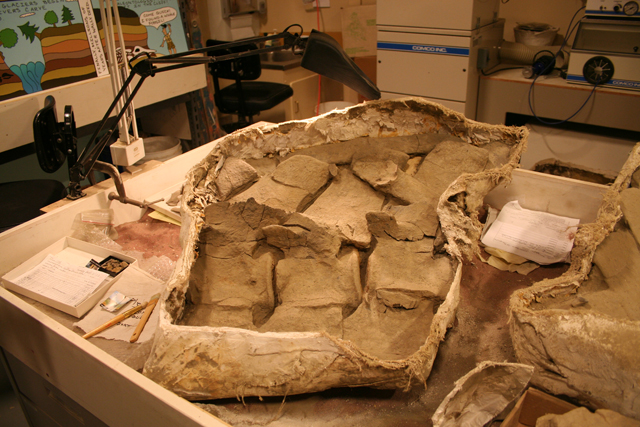

Part of the interest of sharks in the Chesapeake Bay extends well beyond the current age, or even the beginning of recorded history. The nearby Calvert Cliffs are a veritable mine of fossilized bones and teeth for sharks from the Miocene Epoch – roughly 23 million to 5 million years ago – and the other marine animals they encountered.

The Calvert Marine Museum on Solomons Island serves as an entr