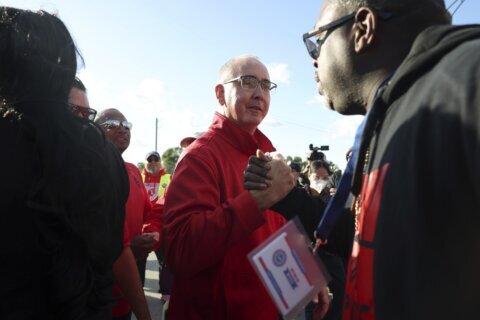

WAYNE, Mich. (AP) — Throughout its 5-week-old strikes against Detroit’s automakers, the United Auto Workers union has cast an emphatically combative stance, reflecting the style of its pugnacious leader, Shawn Fain.

Armed with a list of what even Fain has called “audacious” demands for better pay and benefits, the UAW leader has embodied the exasperation of workers who say they’ve struggled for years while the automakers have enjoyed billions in profits. Yet as the strikes have dragged on, analysts and even some striking workers have begun to raise a pivotal question: Does Fain have an endgame to bring the strikes to a close?

People with personal ties to Fain say his approach, on the picket lines and at the bargaining table, reflects the bluntly straightforward manner he developed as he rose through the union’s ranks. He is, they say, the right man for the moment.

Others, though, say they worry that Fain set such high expectations for the pay and benefits he can extract from the companies that he risks incurring a personal setback if an eventual deal disappoints union members. A weak settlement could also make it difficult for Fain to expand UAW membership to non-union rivals such as Tesla and Toyota USA — an issue the union has been pushing.

“He’s gotten far more from the companies than anyone, in particular the companies, may have expected,” said Harley Shaiken, a professor emeritus specializing in labor at the University of California Berkeley. “But now is the critical point where you pull the package together. If it isn’t now, when will it be? That is what he’s got to be giving some thought to.”

What began with 7,000 workers at one factory each of Ford, General Motors and Jeep maker Stellantis has grown to 34,000 at six plants and 38 parts warehouses across the country. Officials at all three companies note that they have sweetened pay offers and offered numerous other concessions. In one particularly notable move, GM agreed to bring its new electric vehicle battery factories into the national UAW contract, essentially guaranteeing that workers of the future will belong to the union.

Three auto officials, who asked that they and their companies not be identified so they could speak candidly, say they remain unsure whether Fain has a clear plan to end the strikes or whether he’ll cling to demands that the companies say would be so costly as to jeopardize their ability to invest in the future.

Fain, who in March narrowly won the UAW’s first-ever direct election of a president, had campaigned on promises to end cooperation with the automakers, essentially declaring war on them. He has complained that the highly profitable companies have failed to restore concessions the union members made before and during the 2008-2009 Great Recession, when the industry was teetering.

Some auto executives have accused Fain of performative showmanship and of failing to negotiate seriously. Yet his strategy has so far achieved a number of measurable successes: The companies have offered to raise pay increases from single digits to 23% over four years, restore cost-of-living pay increases and end lower wage tiers for many workers.

Yet obstacles remain. The UAW has demanded 36% general raises; traditional defined-benefit pensions for workers hired after 2007; and pension increases for retirees. Fain has even sought 32-hour work weeks for 40 hours of pay — a demand that even many union workers call unrealistic.

On the picket lines, some say they wonder just how long Fain will keep them out.

“If they can’t come to terms, what happens then?” asked Dawn Krunzel, a team leader at Stellantis’ Jeep complex in Toledo, Ohio, one of the first plants to walk out.

Krunzel said she and her husband had prepared for the strike and aren’t yet worried about their finances, though she said some workers are.

All that Fain is seeking, Krunzel said, is for the UAW to be made whole for the concessions that saved the companies when they were in grave financial danger. Retirees, she said, haven’t had pension increases for years. But she said Fain seems “stuck on what he said out there initially” about pay and other demands.

“I’m hoping Fain is smart enough to say, ‘Enough is enough,’ “she said. “You never get everything you want.”

Doc Killian, who works at Ford’s Michigan Assembly plant in Wayne near Detroit, said he thought it was insincere for Ford Executive Chairman Bill Ford to assert in a speech last week that Ford can’t increase its contract offer because higher labor costs would limit its investments in electric vehicles and the factories to build them. Ford’s speech, Killian noted, came a day before the company announced that it was paying out $600 million in dividends to shareholders.

“Saying you’re broke and then all of the sudden passing out dividends because you’re not broke — that flies in the face of your own statement,” Killian said.

The union, Killian said, should hold out as long as necessary to secure bigger raises, the unionization of battery plants and increased pensions.

In a departure from the style of past UAW leaders, Fain has insulted CEOs and publicly revealed the companies’ pay offers. With contempt in his voice, he has likened the UAW’s contract fight to a battle between the beleaguered working class and billionaires. Rejecting the auto officials’ arguments, Fain said the companies can indeed afford to pay more.

“We have plans,” he said. “We have strategies and tactics to keep winning at the table.”

Unlike his predecessors, Fain has recruited outside advisers, some of them specialists in public relations, to assist the union. His communications director, for instance, was a labor organizer for Bernie Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign. The advisers have refined the union’s public image, shaping it with slick videos and appearances by Fain on Facebook Live.

With roots in small-town Indiana, Fain, now 54, was known as a straight-arrow young man who respected teachers and coaches at Taylor High School near Kokomo, from which he graduated in 1987. Paul Nicodemus, a childhood friend, said Fain derived his values from his father, who was Kokomo’s police chief, and his mother, a nurse.

Nicodemus doesn’t recall Fain as being particularly outspoken about economic inequities — probably, he said, because there wasn’t much inequality in Kokomo. Nearly everyone’s parents worked at either Chrysler or General Motors’ Delco factories.

“Shawn was the type that loved to make people laugh,” Nicodemus said. “To know he’s in a spot now that this is not a laughing matter and he’s having to put his foot down — in my eyes, he’s doing a phenomenal job.”

After high school, Fain became an electrician at a Chrysler castings plant in Kokomo and joined the UAW, the union that had represented three of his grandparents. Having risen in the local union to become plant shop chairman, he warned against becoming too chummy with automakers. In 2007, he opposed the union’s leadership, which had agreed to a contract that created lower tiers of wages for new workers. Still, the deal was ratified.

Bill Parker, who chaired the union’s national negotiating committee at Chrysler in those talks, said Fain joined him to oppose the deal. Fain favored a more confrontational stance with the companies than the UAW’s president did.

Fain later took a job with the union’s national staff in Detroit while still pushing to be more aggressive with the automakers.

“He fought for his principles while he was on staff,” Parker said, “and was often reprimanded by those in power.”

When a federal embezzlement and bribery investigation rocked the union starting in 2017 and sent two former presidents and other officials to prison, it opened the door to Fain’s campaign for higher office. In a settlement to avoid a federal takeover, the union agreed to let members decide if they wanted direct elections of leaders. They did. Fain campaigned against an incumbent who had arisen from the union’s old guard, declaring that it was time to fight the companies and end years of coziness.

“What you see is what he is,” Parker said.

Parker, whom Fain tapped to be an assistant, says he feels sure Fain has a plan to end the strike. He just doesn’t know what it is.

Brian Rothenberg, a former union spokesman who now is a public relations consultant, said all UAW presidents struggle over when to take a company offer to members to end a strike.

“There comes a point,” Rothenberg said, “where the members really push if they feel a need for resolution. In the end, this is an employment contract, and the endgame will be a contract.”

Copyright © 2024 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, written or redistributed.