Twenty years after the nuclear attack on Hiroshima, physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, often credited as the father of the atomic bomb, said he didn’t have a good answer to the question of whether dropping the bomb on Japan was necessary.

Oppenheimer in 1965 told CBS News that he believed the decision to use the bomb in WWII was arrived at by military leaders “in good faith, with regret, and on the best evidence that they then had” at the time.

Germany had already surrendered by the time Oppenheimer tested the atomic bomb in New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, but Japan was fighting on. An atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima three weeks after the test. A second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki days later. Japan formally surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945.

“The ending of the war by this means, certainly cruel, was not undertaken lightly,” Oppenheimer said in the interview. “But I am not, as of today, confident that a better course was then open.”

Oppenheimer had built the weapon that won the war, but questioned the “sin of pride” of the scientists involved in the bomb’s creation. The development of the bomb left its mark on many of those engaged, he said.

“I think when you play a meaningful part in bringing about the death of over 100,000 people and the injury of a comparable number, you naturally don’t think of that with ease,” he said. “I believe we had a great cause to do this, but I do not think that our consciences should be entirely easy at stepping out of the part of studying nature, learning the truth about it, to change the course of human history.”

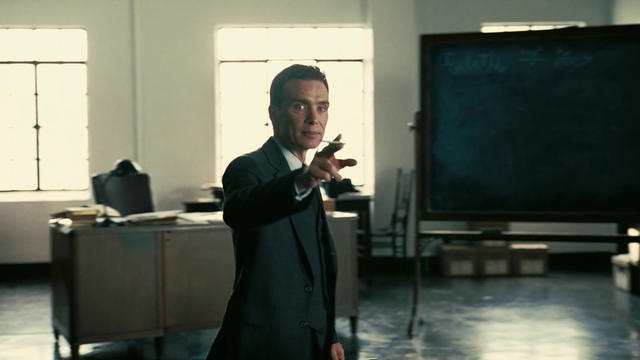

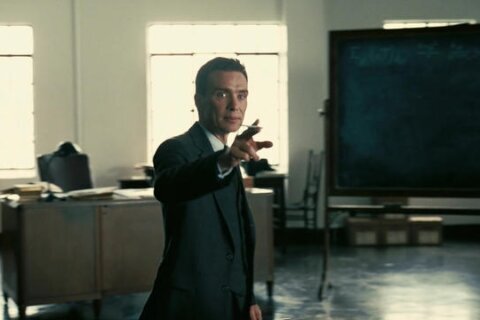

The story of Oppenheimer and the development of the atom bomb is detailed in “Oppenheimer,” a Christopher Nolan film starring Cillian Murphy, set for release Friday. The movie is based on “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” a biography written by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin.

“It’s complicated to take on a historic icon like Robert Oppenheimer and deal with the history faithfully and yet turn it into a cinematic experience,” Bird told CBS “Sunday Morning” ahead of the film’s release.

Oppenheimer, born Julius Robert Oppenheimer in 1904, grew up in New York City, according to a Manhattan Project National Historical Park post. He attended the Ethical Culture School and, after his graduation in 1921, he traveled to Germany and fell ill. The following year, he went to New Mexico to recover. Twenty years after his trip, he suggested the state’s isolated Los Alamos Ranch School be used as a secret laboratory during the Manhattan Project.

He began studying at Harvard University in the fall of 1922 and was accepted to study at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, England, in 1925. Oppenheimer was awarded a doctorate in physics in May of 1927. In 1929 he started teaching at the University of California, in Berkeley.

He began a relationship with medical student and Communist Party member Jean Tatlock in 1936. He engaged with the politics, but never joined the Communist Party. Oppenheimer’s relationship with Talock ended in 1939. That year, Oppenheimer met his future wife, Katherine “Kitty” Puening. She was a member of the Communist Party.

Oppenheimer’s communist connections led to difficulties getting a security clearance when he was called on by Army Gen. Leslie Groves to develop the atomic bomb, Bird said.

Others believed Groves’ pick was outlandish, Bird said, but the Department of Defense noted Groves and Oppenheimer “had the talent, drive and leadership qualities that enabled production of the bomb on a very short timeline.”

“[Groves] could see in Oppie the smarts and the charisma to bring all the scientists together in this secret city and make it happen,” Bird said.

Oppenheimer started collaborating with physicist Ernest Lawrence on questions of atomic bomb development early in 1941. In the spring of that year, the Roosevelt administration created a committee on atomic bomb creation. Groves took charge of the project in September of 1942 and, with his support, Oppenheimer was appointed as the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory at a secret laboratory.

Barracks and laboratories were built in Los Alamos. Scientists worked day and night. Oppenheimer chain smoked four to five packs of cigarettes a day as he worked. He was also under surveillance during the bomb’s development. His home and office were wiretapped.

In July of 1945, the bomb was tested in the desert of New Mexico.

“Oppenheimer supposedly said, ‘Lord, these affairs are difficult on the heart,’ before the final test of the atomic bomb,” Alan Carr, historian at Los Alamos National Laboratory, said.

He recalled the moment years later, saying it brought to mind a line from Hindu scripture.

“Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds,” he said in a 1965 NBC interview.

Oppenheimer plunged into a “deep depression” after the war, Bird said.

In the 1965 interview, Oppenheimer told CBS News that he tried to think and talk of hopeful things.

“There are 100 reasons for seeing no hope at all, and I take it for granted that everybody can think of them without being reminded,” Oppenheimer said. “It’s harder to think of anything on the other side and I have tried to say that, however frail and however tentative and however limited, they do exist and they look to me like a bridgehead to a livable future, but not without work.”