Fans of the band Wilco could have reasonably interpreted frontman Jeff Tweedy singing “I Am Trying to Break Your Heart” at an Aug. 13 concert at St. Louis Music Park as the universe explaining the past year or so.

For example, 30-year-old fan Lazarus Pittman had planned to see Wilco and co-headliner Sleater-Kinney in August 2020 at the open-air venue in this suburb west of St. Louis. Then the show was postponed because of the covid-19 pandemic. Pittman got sick with the coronavirus. He quit his job as a traffic engineer in Connecticut to relocate to St. Louis for his girlfriend — only to have her break up with him before he moved.

But he still trekked from New England to Missouri in a converted minivan for the rescheduled outdoor show. “Covid’s been rough, and I’m glad things are opening up again,” he said.

Yet hours before Pittman planned to cross off the concert from his bucket list, he learned the latest wrinkle: He needed proof of vaccination or a negative covid test from the previous 48 hours to enter the concert.

The bands announced the requirements just two days earlier, sending some fans scrambling. It was the latest pivot by the concert industry, this time amid an increase in delta variant infections and lingering concerns about the recent Lollapalooza music festival in Chicago being a superspreader event.

After more than a year without live music, promoters, bands and fans are eager to keep the concerts going, but uncertainty remains over whether the vaccine or negative-test requirements actually make large concerts safe even if held outdoors.

“Absolutely not,” said Dr. Tina Tan, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases at Northwestern University. “There is just too much covid that is circulating everywhere in the U.S.”

During the first months of summer, large outdoor venues such as Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Colorado and Ruoff Music Center in Indiana again hosted bands such as the String Cheese Incident and Phish, with sellout crowds of mostly maskless people inhaling marijuana or whatever other particles were possibly around.

Then the delta variant surge in July prompted renewed concerns about large gatherings, even at such outdoor venues.

Tan, and other doctors, warned that Lollapalooza, with an estimated 385,000 attendees from July 29 to Aug. 1, was a “recipe for disaster” even though organizers instituted a vaccine or negative-test requirement.

It turned out that Lollapalooza was not a superspreader event, at least according to Chicago Department of Public Health Commissioner Dr. Allison Arwady, who reported that only 203 attendees were diagnosed with covid.

Tan said she is skeptical of those numbers.

“We know that contact tracing on a good day is difficult, so think about a venue where you have hundreds of thousands of people,” Tan said. “That just makes contact tracing that much more difficult, and there always is a reluctance for people to say where they have been.”

But Saskia Popescu, an infectious disease expert at the University of Arizona, said she sees the Lollapalooza data as “a really good sign.” Still, an outdoor concert with the new entrance rules is not without risk, she said, particularly in states such as Missouri, where the delta variant has thrived.

“If you are considering an event in an area that has high or substantial transmission, it’s probably not a great time for a large gathering,” Popescu said.

Recently, two of the country’s largest live music promoters, AEG Presents and Live Nation Entertainment, announced they would begin requiring vaccination cards or negative covid tests where permitted by law starting in October. But not all bands and venues are instituting such measures. And some simply are postponing shows yet again. For the second straight year, organizers canceled the annual New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival slated for October.

Theresa Fuesting, 55, wasn’t planning on coming to her first Wilco show, even though she had four tickets, until the bands announced the new rules.

“I still think it’s a threat even though I am vaccinated,” said Fuesting, who lives just over the river from St. Louis in Illinois.

For promoters, ensuring that people like Fuesting feel safe enough to use their tickets affects their bottom line, said Patrick Hagin, who promoted the Wilco concert and serves as a managing partner of The Pageant and Delmar Hall music venues in St. Louis. Even if the tickets are already purchased, bar and merchandise sales at the venue suffer if fans are no-shows.

“Also you worry: Is this person who purchased a ticket going to even come in the future?” said Hagin.

In non-covid times, more than 90% of ticket buyers ultimately attend, Hagin said. During the pandemic, that number has been as low as 60%.

Hagin said he is temporarily offering refunds for shows at his venues. St. Louis Music Park did not offer refunds for the Wilco concert and told fans on its Facebook page that it was instituting the requirements “based on what each show wants.” The venue operators did not answer questions for this story.

Jason Green, unable to get a refund for the Aug. 13 show, sold his two sixth-row tickets for $66 — which was $116 less than he paid for the pair in March 2020. He was concerned the venue’s new requirements weren’t enough.

“You want to wait and see if that’s a legit thing that is keeping things from being spread,” said Green, 42, who lives in St. Louis and is fully vaccinated against covid.

He skipped the concert even though he and friends in a comic book collective liked Wilco enough to name a recent comic after the band’s album “A Ghost Is Born.” The band enjoys a loyal local following: Tweedy is from Belleville, Illinois, just across the Mississippi River, and the band played its debut concert in 1994 in St. Louis.

Fuesting and Pittman took their chances.

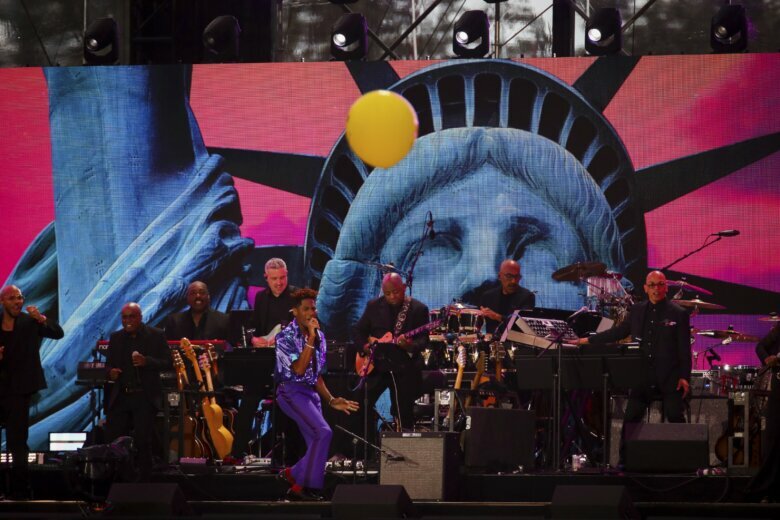

This was many fans’ first visit to the new venue, an open-air space beneath a curved roof. It was supposed to open last year but was delayed because of the pandemic.

Fans passed through metal detectors and quickly showed their vaccine cards or test results to people sitting at tables. Out of about 2,500 attendees, the venue had to turn only four people away; one of them left, got a test and then returned, Hagin said.

“I was very encouraged just by how positive the compliance was,” he said.

Fortunately, Pittman had a photo of his vaccine card on his phone, which organizers accepted.

“It was so much fun,” said Fuesting, who wore a mask for the whole show. “I just liked the energy of the crowd. They were all just such super fans and singing along to every song.”

The band encored with their classic tune “Casino Queen,” the name of a riverboat casino in East St. Louis, Illinois.

“Casino Queen,” Tweedy sang, “my lord, you’re mean.”

So is covid. But for Pittman, who didn’t wear a mask, the show was worth the gamble. He said he was so into the music, he could push the coronavirus from his mind, at least for a bit.

“They just played all of my favorite songs, one after another,” Pittman said. “I wasn’t even thinking about it.”