In February 1964, an English boy band called the Beatles made its US television debut.

Beatlemania, the intense fan frenzy directed towards the fab foursome, was gripping America and the group’s performance at the Ed Sullivan Theater was punctuated by fervent screaming from the studio audience.

In May 2019, over 55 years later, another band of foreigners played the same theater.

The visual similarities were striking — and intentional.

The Korean newcomers sported the same style of slim-fit suits and floppy bowl cuts, emblazoned their name on their drum kit in the same font used by the Liverpudlian hitmakers, and even made their broadcast in black and white.

But this wasn’t the Beatles. It was BTS — a seven-man South Korean mega-group which is quite possibly the biggest boy band in the world right now.

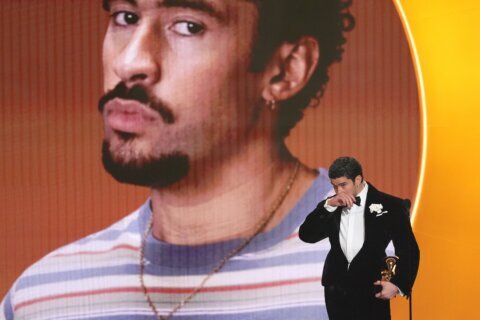

In April, BTS became only the third group in 50 years to have three number one albums on the Billboard 200 charts in less than 12 months, joining the ranks of The Beatles and The Monkees. The next month, BTS became the first group in Billboard history to spend five weeks at number one on the Billboard Artist 100 chart.

Like the Beatles, BTS had traveled from another continent to perform for their enormous American fan base. But that the South Korean stars had managed to crack the American market was perhaps an even greater achievement. Most of BTS’s songs are in Korean, the group only has one fluent English speaker, and they were selling Americans a distinctly Asian brand of sex appeal.

The K-pop band that could

Six years ago, when BTS released their music video debut “No More Dream” in June 2013, it wasn’t obvious that they would be K-pop’s breakout success story in America.

The group, comprised of Kim Tae-hyung (better known as V), Jung Ho-seok (J-Hope), Kim Nam-joon (RM), Kim Seok-jin (Jin), Park Ji-min, Jeon Jung-kook, and Min Yoon-gi (Suga), presented itself as rebellious “bad boys,” sporting gold chains, bandannas and heavy black eyeliner. The aggressive, rap-heavy track urged young people not to be defined by their parents’ aspirations.

South Koreans, however, weren’t blown away. The single debuted at number 84 on Korea’s government-sponsored Gaon Music Chart.

At the time, boy bands EXO, Big Bang and SHINee dominated the K-pop charts. And while those groups sometimes referenced hip-hop in their songs, they tended to have a more clean-cut image and sing pop songs about romance. In EXO’s 2013 hit “Wolf,” for instance, the band members howl and compare themselves to an animal who has been tamed by an alluring woman.

But BTS, who were then all aged between 15 and 20, had something else that set them apart: they had been developed by start-up label Big Hit Entertainment, not one of the big three record companies — SM Entertainment, JYP Entertainment and YG Entertainment — which formed in the late 1990s, when K-pop was starting to take off.

To dominate South Korea’s ultra-competitive, $4.7 billion K-pop industry, those labels had established intense pop factories that found and developed talent to form money-making groups.

The labels auditioned thousands of idol hopefuls a year, often aged between 10 and 14, who would become trainees at so-called K-pop farms and take part in a grueling, full-time rigorous training program in dance, singing and even make-up. Eventually, the lucky ones were selected for a K-pop group and tied in to long contracts that restricted their personal lives and sentenced them to years of limited pay. They had to conform to the rigid world of K-pop, where members are given designated roles within a group, such as leader, dancer or “visuals” — the eye-candy of the group.

Like other idol groups, BTS were manufactured. But its upstart label Big Hit Entertainment had to do something different to break through.

Wearing their hearts on their social

From the start, Big Hit Entertainment faced a challenge.

Lacking the industry connections and big money of the industry giants, the label relied heavily on social media to promote the group.

BTS were one of the first K-pop groups on Twitter, says Michelle Cho, a professor of East Asian Studies at University of Toronto. The band also posted vlogs on YouTube and shared the minutiae of their lives on Korean livestreaming platforms AfreecaTV and V Live.

In one clip, singer Jungkook makes instant ramen in a modest kitchen. Using tongs, he pulls a noodle to his mouth. “It’s perfect,” he says. In the past 10 months, that V Live clip has been viewed over 7.6 million times.

The internet is full of these kinds of mundane BTS moments: the members cuddling as they snooze, eating meals, sitting in taxis and pulling pranks on each other. They take a variety of forms — casual posts, live-streamed video diaries, or produced episodes of their reality TV-like web show “Run BTS!”

“I think that for some people it’s quite alienating to encounter other K-pop (groups) … that they know are a product of this very rigorous training system that (they believe) makes them a bit less authentic,” Cho said. “BTS are quite different because their whole concept from their inception was that they were going to be honest purveyors of the experience of youth.”

The videos build up seemingly authentic characters for the members: V is the quirky one, Jimin the flirty one, Jungkook the supernaturally talented youngest member. J-Hope is high-energy, Suga the brooding musician, Jin the handsome one, who often reveals himself as a pun-loving dork. And RM, the preternaturally mature group leader. Among fans online, the members are often represented by a different animal emoji.

“They’re superstars, but they have a human side as well,” says YJ Chee, a 24-year-old Singaporean based in the US who describes himself as a member of ARMY, the name BTS uses to refer to its fans and an acronym for “Adorable Representative M.C. for Youth.” “It makes them relatable.”

Of course, it’s easy to be cynical about the authenticity of the image they present online. BTS are closely managed and never mention their romantic lives. But the clips have created a kind of intimacy between BTS and their fans that other K-pop groups have since tried to imitate.

“They don’t distance themselves that much from their fans,” says David Kim, who runs YouTube channel DKDKTV where he analyzes K-pop. “They just show themselves how they are — they show the good and bad. I think that’s what’s different from other idols.”

And with the Korean market lukewarm on BTS, that ARMY helped the band break America.

Becoming a household name

BTS looked abroad early. In 2014, while still relatively low profile on home turf, BTS began chipping away at the US market. They were a breakout success at that year’s KCON, a K-pop convention in Los Angeles, where they performed in schoolboy outfits. Their music made nods to hip-hop and electronic dance music (EDM), genres that were popular in the West.

BTS toured again in the US in 2015, and in 2017 — now sporting their trademark colorful hairstyles — they went back for their biggest year yet stateside, becoming the the first K-pop act to win a Billboard Music Award and make the top 10 of the Billboard 200 charts. In November 2017, they made their US television debut, performing at the American Music Awards.

They weren’t the first K-pop group to try to break the overseas market. YG Entertainment’s Big Bang had gained some overseas success, winning Best Worldwide Act at the 2011 MTV European Music Awards, and in 2012, becoming the first K-pop group to break into the Billboard 200 chart.

But the personal connection with their fan base established through their social media presence gave them a huge advantage, says Cho. The BTS ARMY began to act as a network of unpaid translators, producing English subtitles and texts of their content, connecting BTS with their non-Korean speaking audience.

Most of BTS’s Twitter posts aren’t in English, but today the group has over 20 million followers on the platform, more than Beyonce or UK hit-maker Ed Sheeran. Individual BTS members don’t have social media accounts, meaning the group’s fan following was concentrated on one account per platform.

In 2017, as their fame rose stateside, they landed appearances on “The Ellen Show” and Jimmy Kimmel.

Cho believes it was the group’s large social media following that got the US TV shows interested.

“(BTS) really had to rely on their fans to be their advocates whereas other groups had a bigger machine behind them,” Cho adds. “I think it was … the power of their numbers of Twitter followers … which really brought them a lot of media attention, which helped them become a household name.”

An ecosystem of fans

BTS aren’t just savvy at social media — to their fans, they are trailblazers within the K-pop genre.

While K-pop hits are mostly not written by the band members,many BTS songs have one of the members credited as a writer or producer, particularly J-Hope and former underground rappers Suga and RM. But more importantly, their songwriting — particularlyin their earlier works — goes beyond the love-lorn lyrics of some other pop hits.

In 2014’s “Spine Breaker,” BTS hit out at young people who are using their parents’ money to buy expensive things. In 2015’s “Baepsae” they rebuke the older generation for promoting the idea that the younger generation are lazy. In 2018’s “Idol” they discuss the importance of loving yourself, regardless of what others think.

BTS’s works also often reference literature or philosophy. Their latest album, “Map of the Soul: Persona,” is a reference to the work of psychiatrist Carl Jung — and even the album’s party hit “Dionysus,” ostensibly an ode to getting drunk, references the Greek god of wine.

As new fans tuned in to BTS, they found a group with elaborate music videos and experimental fashion that sometimes bordered on feminine, at least to Western eyes. Both on and off stage, BTS members wore chokers, blouse-like, silk shirts and visible makeup that made them look glossy and beautiful in a way that didn’t necessarily fit with the the traditional Western conception of masculinity.

“The more time fans spend thinking about all of the different elements that go into the group that they’re interested in, the stronger that attachment will be,” Cho says. “I think it’s a really potent mix, you’re not just a casual fan of BTS, you have to be initiated into their world and then you get sucked in.”

Another BTS?

To some, BTS’ success is a sign that the so-called hallyu wave — the global popularity of South Korean entertainment — isn’t just coming, it’s crashing upon US shores.

In April, Korean foursome Blackpink became the first female K-pop group to play Coachella. Seven of the top 10 artists on Billboard’s social charts for the first week of June came from South Korea.

But the effects of BTS’s breakout success might be broader. Some of David Kim’s 500,000 subscribers have also told him they’re learning Korean to better understand BTS’s message.

“I feel extremely proud, the Korean pride is exploding,” David Kim says. “It’s absolutely unbelievable. If you think of this small country … and this small group that doesn’t even speak English, spreading all this Korean culture and topping the charts and stuff, it’s just unbelievable.”

Cho says BTS’s aesthetic, which is a representation of East Asian masculinity, is helping to change what mainstream viewers think about the possibility of gender presentation and what Asian bodies represent.

Suk-young Kim, Director for the Center for Performance Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) thinks BTS are doing a lot for Asian males, who haven’t always been presented well in US media. “BTS’s ubiquitous visibility and positive image will do much to create cool ‘Asianness,'” she said.

But she cautions against seeing BTS as a game changer for K-pop overall.

“BTS and K-pop should not be bundled up together,” said Suk-young Kim. “BTS, in a way, has been breaking a lot of the conventional molds of K-pop.”

Some fans feel the same way, pointing to how BTS were never especially popular in South Korea, and instead had to rely on the online fandom to break into foreign markets.

Kim believes the next BTS isn’t coming anytime soon.

“Currently (BTS) are being compared to The Beatles and that is just crazy,” he says.

“The Beatles in world history are one of the top, top groups. And a K-pop climbed up the ladder up to that level. I think it’s going to be unrivaled for at least decades.”