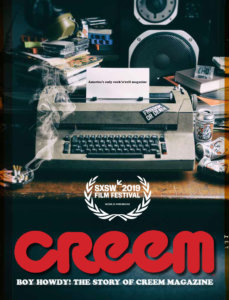

Creem billed itself as “America’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll Magazine.” That wasn’t just a jab at Rolling Stone, which almost from the beginning was trying to turn into the slick lifestyle magazine it is now; it encapsulated what the magazine was all about. It wasn’t just about rock ‘n’ roll; it actually was rock ‘n’ roll.

Just like the music it covered, it was loud; it was disrespectful; it was flamboyant; it was sometimes incredibly smart in a direct, guttural, colloquial way. It was sometimes gloriously, brilliantly stupid; it was sometimes just plain stupid. Also like rock ‘n’ roll, the magazine — and some of the people who made it, wrote for it and lived for it — couldn’t last forever.

But local filmmaker Scott Crawford, fresh off the D.C. hard-core punk documentary “Salad Days” (2014), has captured the story in “Boy Howdy: The Story of Creem Magazine,” which opens locally at the AFI Silver Theatre in Silver Spring on Saturday night.

“It’s a story I’ve always wanted to tell,” Crawford told WTOP. He was exposed to the writing in Creem as a kid; and when he founded Harp, his own D.C.-area fanzine, his goal was to work with “as many of the Creem writers I grew up reading as possible.”

A lot of them show up in “Boy Howdy,” including Jaan Uhelski, who wrote the film, Cameron Crowe, former editor Dave Marsh and rock-critic guru Robert Christgau, as well as posthumous interview clips with legendary critic Lester Bangs and Creem publisher Barry Kramer, who died of overdoses in 1982 and 1981, respectively.

“The influence that this magazine has had on modern-day journalism … it’s huge,” Crawford said. “Anyone who reads Pitchfork or Rolling Stone today owes a lot to the early writers of Creem, who created this style that’s never been duplicated but always copied.”

Crawford wanted to document Creem’s “freewheeling approach to writing.” One legendary example is Bangs’ paean to Lou Reed’s “Metal Machine Music,” an hourlong fantasia of tape loops and feedback. In 2,475 words, Bangs wrote, “Anybody who got off on ‘The Exorcist’ should like this record. It’s certainly far more moral a product,” as well as references to Barry White, Idi Amin, the Pleasure Chest, the opera “Rigoletto” and the TV show “Lucas Tanner.”

The film also documents the time Bangs wrote a J. Geils Band concert review on stage while the band played, as well as the time Uhelski took the stage with Kiss in full makeup.

But Crawford also wanted to show the passion with which the Creem staff worked.

“The writers were encouraged to write what they felt, and if it took 10,000 words … “ Crawford shrugged. “There’s a freedom in that. It was a different age.”

‘Creem was our Facebook’

From its founding in 1969 upstairs from a head shop in a seedy section of Detroit and moving through the ‘80s, Creem sought to document its time and place.

“If you live in the Midwest,” Marsh said in a vintage interview clip included in the film, “the realities of the situation will force you to understand very quickly that it’s not all laid back and peace and love and good vibes and groovy; it’s hard work; it’s discipline; it’s making something out of the ugliest part of the universe.”

That’s what Detroit bands such as The MC5, The Stooges and Alice Cooper — three of Creem’s favorites — did, and that’s what Creem did as well. In a time when rock ‘n’ roll was turning into pop music with swelling strings and denim-clad crooners winking about afternoon delights, Creem documented a scene that rose in opposition and spread nationally and worldwide. And the magazine acted as a form of tribal communication.

“Creem magazine was our Facebook,” Wayne Kramer, of the MC5, tells Crawford in the movie. “Who’s doing what, who’s doing something cool, who’s doing something stupid.”

They worked hard, and they cared, because they felt their words mattered, and they probably did. Crawford said he wanted to make the audience feel the 20-hour days that Creem staffers put in and the devotion to their craft. “These people were living it, and that wasn’t always a good thing necessarily. This was not like a day job … these people devoted their lives to this music, and documenting it, and writing about it.”

In one of the most affecting passages in the film, a latter-day Marsh tells Crawford, “Even in rock ‘n’ roll it had come to pass that there was a stuffy way of dealing with people. And I thought part of your job as a human being was to oppose that. And if it meant you bled a little for it, so what? Because there’s some other kid who’s gonna read this thing, and be freed by it.”

Crawford cuts directly to REM frontman Michael Stipe, who said that as a queer high school outcast, “my entire life shifted” when he saw Creem for the first time. He had found his “gang.”

A lot of people found their gang in the pages of Creem. In addition to Stripe, the film includes interviews with musicians Peter Wolf, Thurston Moore, Kirk Hammett, Joan Jett, Paul Stanley, Gene Simmons and Chad Smith.

“It was really pretty easy” to get people to talk about Creem, Crawford said. “They’re there because they love the magazine and what it did for them, not just professionally but personally. … For the most part, everyone we asked wanted to be a part of it.”

The rest was just a matter of logistics and scheduling, Crawford said, although even that was no small matter: “We literally crisscrossed the country many times.”

‘Vacation’

After launching a Kickstarter fundraising campaign in 2016, Crawford is now showing the completed film at festivals and looking for a distributor. He’s open to showing “Boy Howdy” theatrically or through streaming.

As for his hometown premiere on Saturday night, Crawford said, “I can’t wait. … I have a special place in my heart for the AFI. It should be a fun night.”

He said he went straight from the making of “Salad Days” into “Boy Howdy,” and now he’s at a bit of a loss — but not much of one.

“For the last seven or eight years I’ve known exactly what I wanted to do,” he said. “And now all I know is I want a vacation.”