At a recent event at the Willard InterContinental Hotel, Library of Congress “Baseball Americana” exhibit curator Susan Reyburn dispelled some of baseball’s greatest myths, including its origin story. In so doing, she extolled the Library’s much more evidenced-based findings about the history of the sport.

If it feels like the Library has found itself a little under the influence of our national pastime recently, that’s no accident.

“Since the Library collects to document the American experience and the breadth of the culture, baseball is such an integral part of the culture that it’s there,” said Jeff Flannery, head of the Library’s References and Reader Services Section.

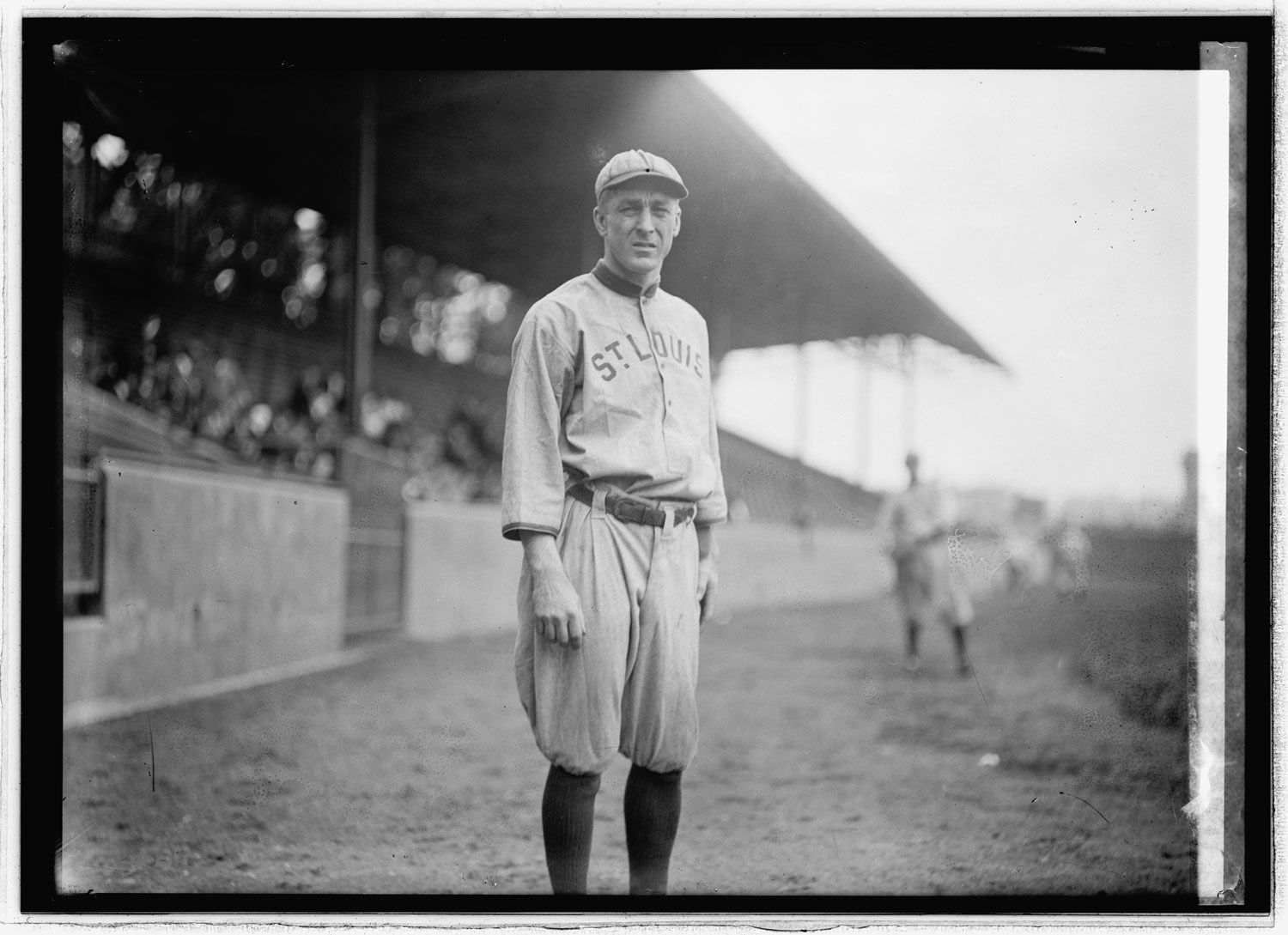

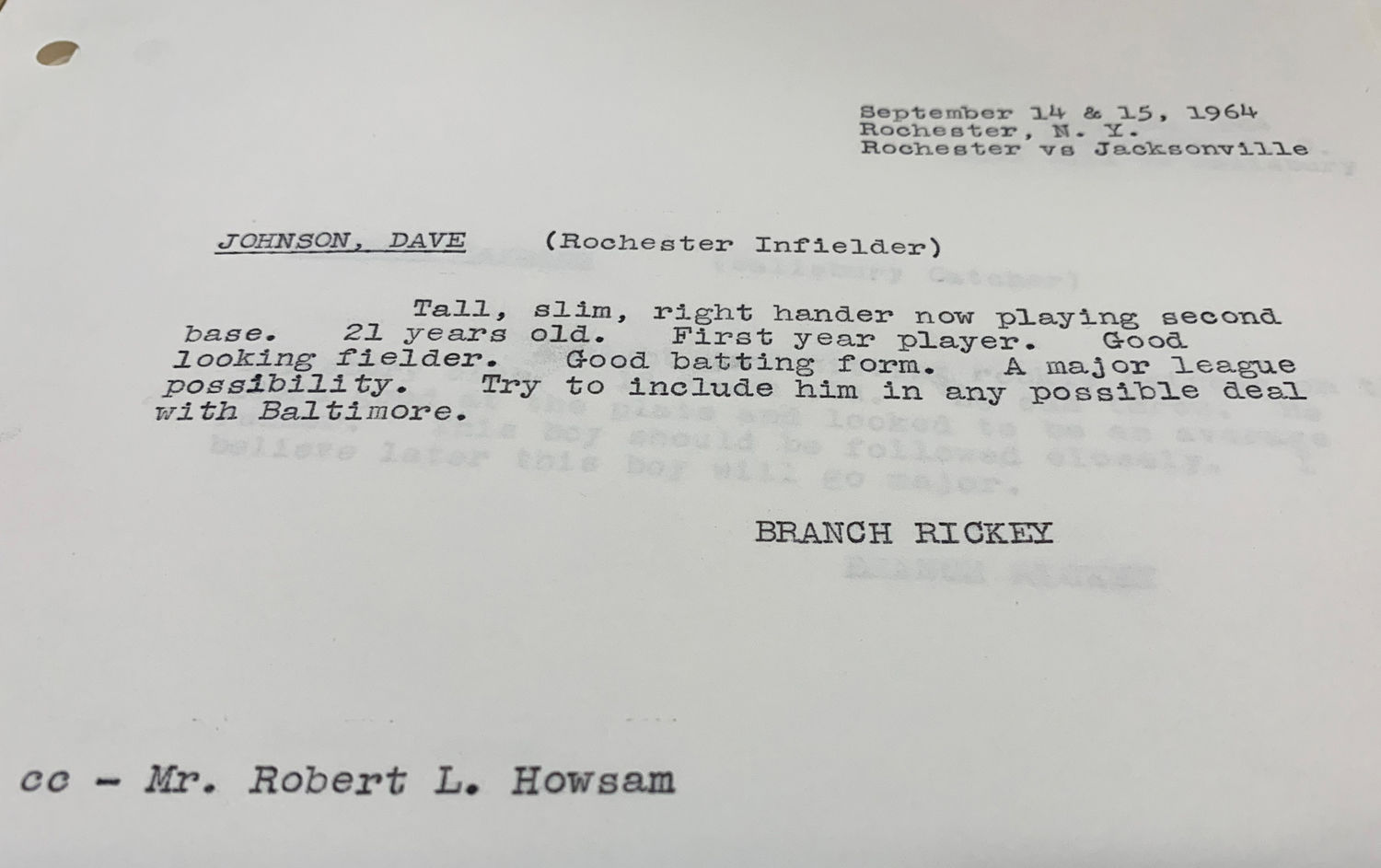

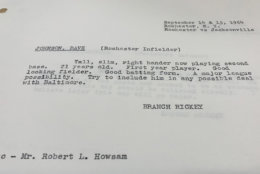

While the “Baseball Americana” exhibit itself is refreshing some of its items just in time for Opening Day, the Library has made strides on another effort involving baseball history. The Library’s latest foray into the national pastime was announced last fall, as one component of the new By the People project — a crowdsourcing effort to help digitize historical documents — included Branch Rickey’s baseball scouting reports. Flannery is also the curator for Branch Rickey’s papers and, like Reyburn, a die-hard baseball fan.

“This collection, to my mind, is unique as far as a baseball executive’s papers,” he told WTOP. “The fullness, the richness of it? I’m not aware of any other collection in a public repository that has this depth and breadth to document the operations of baseball.”

Baseball’s roots in Washington run deep beyond just the Nationals or Senators before them. According to Flannery, President Andrew Johnson was sent an honorary membership to the Washington Baseball Club. President William Howard Taft was given season passes by the Commissioner of the American League.

Some government officials even played the game. Benjamin Brown French was the Commissioner of Public Buildings under Franklin Pierce in the 1850s when, as a 50-something, he played for an amateur baseball team in Washington.

But some pieces of history, like Rickey’s documents, have been more intentionally researched. While the By the People project has successfully digitized the 2,000 scouting reports, those comprise just three of the 87 boxes of Rickey’s files, which also include correspondences, memos, and other printed material that document Rickey’s career in baseball from player to legendary talent evaluator.

While the Library has no intent to spend the time digitizing every last such piece — there are more important matters of American history of which to attend, from the likes of Walt Whitman and Rosa Parks — they serve as a reminder of the breadth of information the Library takes in, roughly 15,000 new pieces each day.

It’s all too much work for the staff to try to bring online, where it can be more effectively searched and studied. So they developed their own open source software to allow the public to be a part of the archiving process.

“A lot people say that they’re interested in history, that they’re history nerds, but they don’t necessarily come with a historian’s training,” said Lauren Algee, a senior innovation specialist and community manager for By the People. “So we tried to scaffold it so that they don’t need it, that this is really for anyone who wants to participate.”

Rickey’s scouting reports are only one segment of the history being cataloged in this first round, though. Other historical documents include diaries of American Red Cross founder Clara Barton, letter sent to and from Abraham Lincoln, dispatches of Union Civil War veterans, and writings of Mary Church Terrell, a civil rights and suffrage advocate. The roughly 2,000 pages of Rickey’s scouting reports are just a fraction of the 10,000+ pages that have been transcribed so far from these collections, but there are still 20,000 pages to go.

There are no age or experience requirements to participate. Transcribers range from middle school students to retirees, academics to just those interested in learning something new. You don’t even have to register to help transcribe, though you do in order to review and tag, which gives you a profile page through which you can connect with fellow transcribers.

“It’s really something that people are enjoying doing together and building community around,” said Algee.

Getting historical documents digitized not only allows for researchers to be able to conduct keyword searches for names and places, it also helps scholars, who can download them and use textual analysis to look for patterns, as well as those who use accessibility technologies to consume information online.

“The Library is incredible at serving scholars, people with specific research interest,” said Algee. “But we want to make sure also people who come to the Library and just are interested and want to explore, that they understand that the Library is for them as well.”

Hence items like Rickey’s reports, which have proved to be incredibly popular.

“These are like eating potato chips,” said Flannery. “You start to read one, and then you just flip it and you go to the next one, and you keep going. They’re very easily digestible.”

Algee hopes that the Library can build upon the success they have had with that particular archive and continue to reshape the idea of what it means to participate in the historical record-keeping process. She said teachers are holding transcribathons, and even using the handwritten materials to help reinforce reading in cursive.

“Rickey is just the beginning,” she said. “We’re just over the moon that we did it in four months, but we’re even more excited to see what our volunteers can do beyond this.”