WASHINGTON — From Ichiro to Yu Darvish, the modern era of Major League Baseball is chock full of Japanese stars.

The United States and Japan have deeply intertwined and shared history through baseball in a way that continues to shape the game today. An exhibit of that history is on display at the Japanese Information & Culture Center, located at 1150 18th Street Northwest) through Aug. 10.

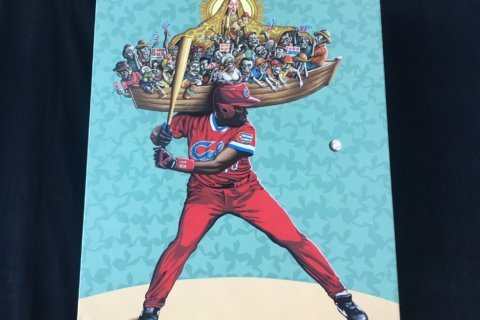

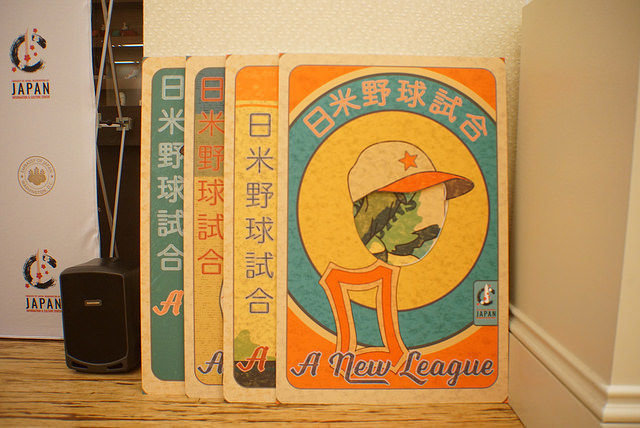

“A New League: Shared Pastimes and the Story of U.S.-Japan Baseball” is a partnership between the Embassy of Japan, the University of Maryland Libraries and Gordon W. Prange Collection. But a lot of the individual artifacts come from one man, Adam Berenbak.

An archivist at the National Archives by day, Berenbak has turned himself into a Japanese baseball specialist, to the point where he was asked to moderate a recent panel at the event space.

“There’s a lot of really wonderful pieces that I love, part of my collection, that we included in here,” he told WTOP. “We tried to be representative of not just a chronological approach to the history of the sport in Japan, but also focusing on the relationship between the U.S. and Japan in terms of baseball and looking at that through the tours of Japan.”

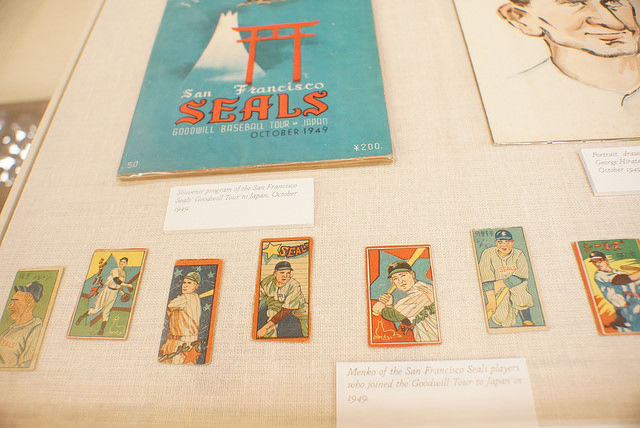

Perhaps the most significant piece for Berenbak is the ticket to the 1934 tour of Japan by the American All-Stars — including Babe Ruth — a trip that helped prompt the origins of professional baseball in Japan. The tours continued up until World War II, and picked up again afterward.

In fact, much of the material from the Prange collection comes from the occupation period in the late ’40s. But the baseball exchange between the countries had existed long before then.

“There had been tours by other groups of baseball teams, either professional or college or amateur, going back to the early part of the century,” said Berenbak.

But one such exchange changed the dynamic forever. In 1964, a 19-year-old left-handed Japanese pitcher was talked into signing a professional contract solely because it meant a trip to the states, a place he idealized from watching reruns of the TV show “Rawhide.”

“He didn’t really want to become a professional baseball player,” author and baseball historian Rob Fitts told WTOP. “He wanted just to go to college and become a salary man.”

That’s how Masanori “Mashi” Murakami ended up in Fresno, California, that summer, pitching for a farm club of the San Francisco Giants. But when the team expanded its roster in September, it called up the young southpaw, who suddenly made history as the first Japanese big leaguer.

“Mashi had very little negative pushback when he came in,” said Fitts, who also wrote Murakami’s biography. “People were very receptive. He was an instant star, because he was the first and it was just cool. So if you look at Sept. 2, 1964 papers from all over the country, you’ll see an article on Mashi.”

He allowed just three runs in 15 innings, going 1-0 with a 1.80 ERA and striking out 15 while walking just one that September. The Giants were thrilled, offering him a contract for the next season. There was just one problem — he was still under contract with his team in Japan.

“At the end of the ’64 season, the Nankai Hawks said, ‘Alright, now you’re a seasoned player, you’re the only Japanese Major Leaguer. You’re coming back to us — you’re going to be a superstar,’” said Fitts.

This sparked something of an international tug-of-war, but eventually the two teams and leagues agreed to let him play the 1965 season in the states, then decide where he wanted to be.

“At the end of the ’65 season, as much as he loved it in the United States, there were family pressures, there were societal pressures, there were friendships that he felt like he needed to return to Japan because that was, as he would say, the ‘moral’ thing to do, but not what he really wanted to do,” said Fitts.

When Murakami returned to Japan, though, he found that his success in America had created ludicrous expectations. The press wondered if Murakami, still just 21, would be the best Japanese pitcher ever, if he would strike out every batter. His inability to do so led to backlash.

“They were merciless,” said Fitts. “So by his first year back, he was a pariah.”

Meanwhile, the animosity between the countries over the contract dispute led each to decide to shut down future exchanges indefinitely.

“The fallout, the argument over this contract was so unpleasant and bad for business for both Japanese baseball and American baseball that they came to a legal agreement, and they promised to respect each other’s reserve clauses and not raid the other league,” said Fitts.

Not until Hideo Nomo retired from Japanese baseball, thereby circumventing the rules, and signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1995, did another from Japan play in Major League Baseball. There is now a posting system in place, but it is still a more restrictive process for Japanese players to reach the majors than from nearly any other country.

Whatever contractual fallout might have come from Murakami’s history-making career, it hasn’t dampened the love for the game in either country. To see the full history of nearly a century of shared passion for baseball, check out the exhibition on display Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. — 5 p.m. through Aug. 10.