WASHINGTON — Every April 15, baseball celebrates Jackie Robinson Day. Every player on every team wears 42 — one of the game’s great traditions, as no doubt each year children ask “why?” prompting Robinson’s story to be told to the next generation. But inevitably, once the dwindling number of black players and managers in MLB are asked about said dwindling numbers, the day ends and, as baseball does, it wakes up April 16 and moves on, another slate of games to be played, the sentiments of the day prior all but gone and forgotten.

But the numbers are stunning, especially for players like Joe Ross. He is the only black pitcher on the Nationals. But much more striking, he and his older brother Tyson make up 14 percent of all black pitchers in the major leagues.

There’s been plenty of hand-wringing about how we got here as a sport, and the answer is complicated and multifaceted. But perhaps the biggest is the disparity in opportunity when young ballplayers hit middle school age. That’s when summer travel ball becomes an indispensable component of many players’ year.

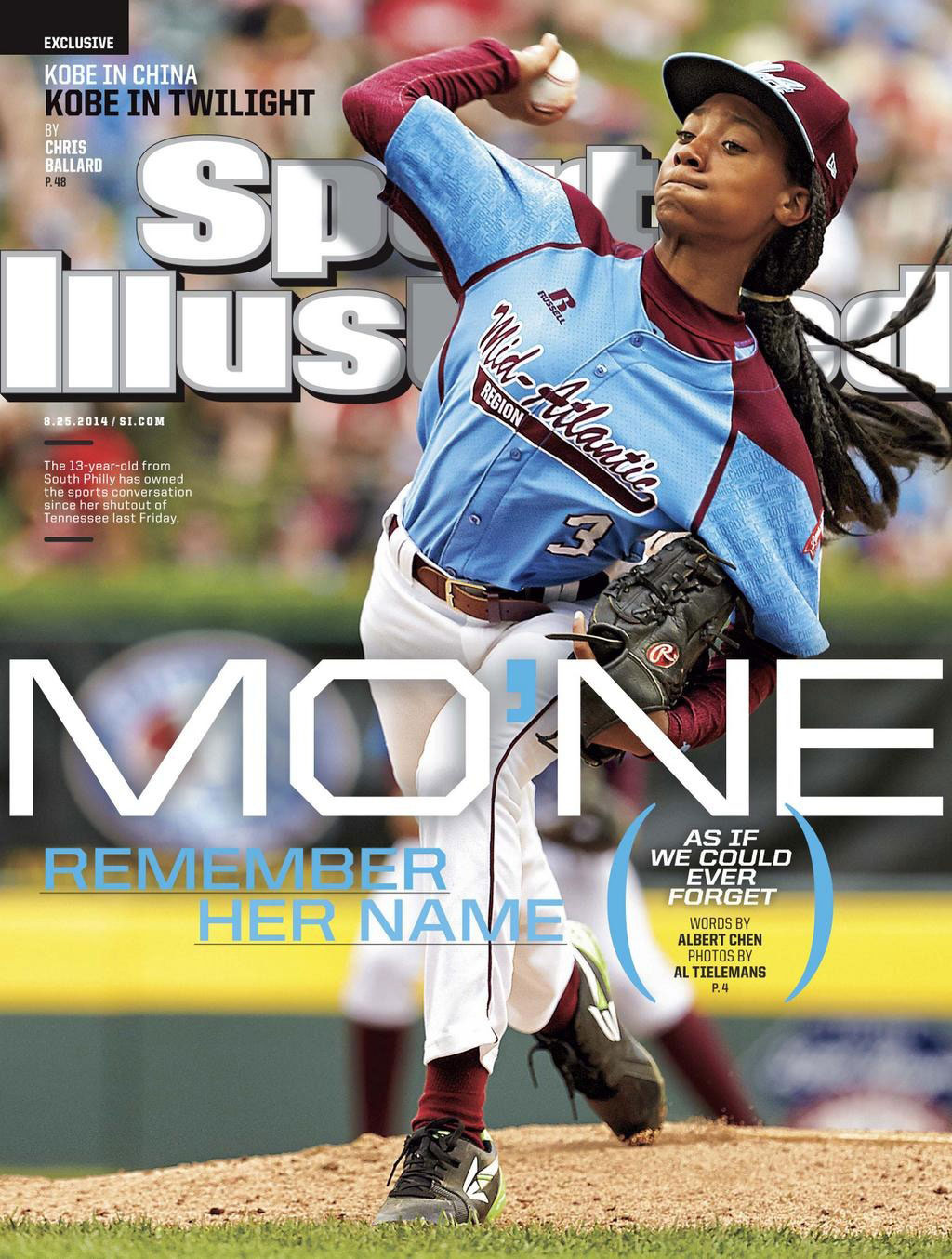

But travel ball is a luxury many cannot afford, and those who only play Little League ball often find themselves falling behind and eventually washing out, turning to other sports.

“That age group has fewer and fewer baseball opportunities,” said Michael Barbera, founder, president and chairman of the D.C. Grays collegiate wood bat team.

“There’s a lot of kids playing Little League Baseball with great volunteers and great coaching. Once they age out of Little League, and they hit that 12-year-old age group, there are many fewer opportunities.”

Barbera and the Grays have partnered with Major League Baseball’s Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities (RBI) program to try to help fill that void. The Grays already partner with the Washington Nationals Youth Baseball Academy in Ward 7, and it’s here, standing at home plate of one of the YBA fields, that they announce the partnership on a cloudless April morning.

It’s fair to wonder, with the YBA already in place, exactly where the RBI program fits in. While the program has existed since 1989, with over 2 million players coming through the program in various cities, on its face it might seem like a direct competitor.

“I think that the Grays are wanting to step into an area of development that the Academy isn’t ready to fill just yet,” said Tal Alter, executive director of the YBA.

While the YBA certainly uses baseball as a hook — it’s right there in the name, and it’s funded by the Major League team — its primary focus is, as Alter puts it, “holistic youth development.” And while the YBA is offering its own summer developmental league for kids age 6-12 on site in the coming months, it doesn’t have anything in place to offer higher level instruction to those above that age range. It may get there at some point, but with the first programming having started in fall of 2013, it just isn’t there yet.

“What I can’t say yet at this stage in our growth is the extent to which we’ll be involved with elite-level development,” Alter said.

Enter RBI.

“We really feel like we’re filling a void that doesn’t exist now for this particular group of kids,” Barbera said. “Our goal has always been to make baseball more accessible to more kids, regardless of their availability to pay.”

Thanks to a donation from MLB and other funding they are still working to acquire, the Grays will aim to fund seven teams — four ages 9-12, two ages 13-14 and a high school softball team at the cost of about $35,000 to $40,000 a year, covering the cost of equipment and uniforms.

Part of that will include donating equipment and apparel to the Sousa Middle School baseball team. The person at this new nexus of accessibility and availability perhaps best able to appreciate its impact is someone who knows how far that team has already come.

Decked out in their bright red tops, sharp and clean in the morning sun, the Sousa Dragons look the part of a team ready to take the field. But just getting to this point, a foregone conclusion for many teams, has been a yearslong process for teacher and head coach Brie Whitmire. She’s been the coach of the program since its inception, five years ago, starting with nine kids. This year, 42 tried out.

“That being said, we’re still getting kids coming in who’ve never played before,” she explained. “They are talented athletes, they just really need maximum repetition. They need more practice than they can get at the middle school level.”

Sousa is ideally situated, just across the street from the YBA, to take advantage of the facility. But baseball is a sport that requires proper equipment, something that just wasn’t in the budget until now.

“Equipment, historically, has come out of my pocket,” Whitmire said. “Kids are sharing bats, sharing gloves. Our uniforms — we looked like the Bad News Bears. I mean, we looked worse than the Bad News Bears.”

Not only will RBI give them uniforms, it will give them equipment they can keep, gloves and bats to call their own. If such luxuries are taken for granted elsewhere, they aren’t here.

“They look like a team right now,” Whitmire said, looking out at her squad of players smiling for the photo op. “And that’s important to them, that’s meaningful to them. Looking like a ballplayer — I’m not going to say it’s half the battle, but it’s up there.”

It’s also important to have someone you can respect and look up to delivering your message. That’s where Brad Burriss comes in.

One of the co-founders of the Grays, he will be providing coaching for some of the RBI teams. Originally from the south, Burriss has lived in the District ever since graduating from Howard, which he attended on a baseball scholarship. He’s a walking, breathing embodiment of where baseball can take you.

“I wasn’t the most talented by far at all,” Burriss said of his high school days. “I was coachable. I had great family structure, who taught me the benefit of saying ‘yes sir, no sir.’ I worked hard. And I was ready for my opportunity.”

Then he shares a life lesson he related to the kids from Sousa, the type of thing he hopes sticks with them as much as technical instruction he can offer along the way.

“In baseball, you can’t put your ball in the star player’s hands,” he said. “Everybody’s got to be ready to play at any moment, at any time. For me, I was able to apply those same principles in my life. How I approached school, internships, jobs, opportunities outside baseball. So when they were ready for me, I was prepared for them.”