This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

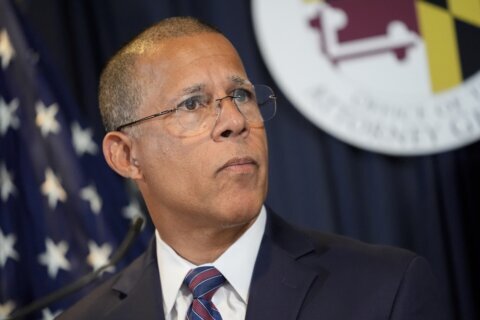

After expressing concerns over the Maryland Department of the Environment’s ability to ensure safe drinking water and to enforce water pollution permits, Attorney General Brian E. Frosh (D) is requesting legislation that would allow the department to impose more penalties on those who violate state water laws.

This comes after Frosh wrote a letter to Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. (R) in December about a report by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that noted a “severe gap” between available staffing and what is necessary to run MDE’s water supply program. Last month, Lawmakers interrogated Environment Secretary Ben Grumbles on a spate of environmental oversight issues such as a recent sewage spill in Southern Maryland and the lack of inspections at poultry farms.

Grumbles promised to increase the number of staff within the department. But in a letter to Frosh, he said the EPA report failed “to capture the complete story” since the department has seen more retirements and staff turnover during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’ve been left with a severely depleted agency — jobs have been eliminated, staff levels especially among inspections, are at dangerously low levels,” Frosh told the Senate Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee on Wednesday. “We believe these failures leave us with an open question about whether drinking water is safe…or how much effluent is coming from polluters that is beyond their permitted amounts.”

However, the bill Frosh is requesting does not try to fix the critical understaffing issues at MDE. Rather, it would give the department the necessary tools to hold polluters and other water violators accountable, Frosh said.

“If the agency replenishes the staff resources that we believe are necessary to inspect permits and enforce the law, we want them to have the tools that are necessary to do so,” Frosh said.

Senate Bill 221 would allow MDE to seek more administrative and civil penalties on private corporations, individuals or municipalities that violate safe drinking water regulations, wastewater facility pollution permits, tidal wetlands restrictions and dam safety regulations. It would also require drinking water and wastewater facilities to annually disclose to the state all their operators who are responsible for the facility.

Administrative penalties are typically less serious and provide quicker relief than civil penalties — which are adjudicated in court, Frosh said.

Last year, MDE noted a total of 15,827 enforcement actions, but almost 15,000 of those actions resulted from the lead poisoning prevention program. Last year marked a significant increase in enforcement when compared to the total 6,581 enforcement actions MDE took in 2020.

Although the bill does not directly address the understaffing issues at MDE, it indirectly creates a “positive cycle” since the money collected from penalties would go into a fund that supports staffing and personnel at MDE, Robin Clark Eilenberg, an attorney at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, told the committee.

Andrea Buie-Branam, who has been a water environmental compliance specialist for MDE for the last decade, said in an interview that she spends most of her time training new staff because so many people quit. This makes it hard for her to get her own work completed, which ranges from visits to wastewater treatment plants to writing up reports, she said. “Until we can stop people from leaving and offer a competitive salary, there is going to be a revolving door,” she said. “We are rarely fully staffed.”

Currently, the vast majority of enforcement actions are addressed through administrative penalties, which are weaker than civil penalties, Eilenberg said. To prevent MDE from relying heavily on administrative penalties, Eilenberg said the bill should also require the department to provide a notice to the Attorney General’s Office of all their administrative enforcement actions to catch those cases that rise to the level of a civil suit or criminal prosecution.

The bill should also require MDE to take into consideration the economic benefit that the violator gained by not complying with the law, Eilenberg said. In other words, the higher the profit, the higher the penalty should be. There should also be an opportunity for citizens to participate in administrative penalty hearings, she continued.

“We have got to strengthen the enforcement capacity at the state level,” Eilenberg said in a phone interview after the bill hearing. “Not only does a penalty potentially alter the future action of a business entity, but it also serves as a warning to all the other entities out there — it’s one of the best tools we have [to enforce state water laws].”

Although business organizations said they supported the bill, they said that the penalties for violations are too high. The bill would allow individual employees to be held personally liable, which means a violation can send a municipal wastewater employee to jail under this bill, Angelica Bailey, the director of government relations at Maryland Municipal League, told the committee.

“We understand completely the need to hold a purposeful violator responsible, but honest human error sometimes happens…and a massive personal penalty just isn’t a fair result,” she said.

A few hours after the bill hearing, the Attorney General’s office announced that it had filed a complaint with MDE in the circuit court against Valley Proteins, a chicken rendering plant in Dorchester County. The plant was operating under a permit that had expired in 2006, or a “zombie permit,” and had pollution violations including unauthorized discharges of wastewater and sludge. Valley Proteins temporarily ceased operations in December after scrutiny from environmental groups and state inspectors.

“The Valley Proteins facility’s recent compliance record indicates a pattern of improper operations and poor decision making that threatens our water and air quality,” Environment Secretary Ben Grumbles said in a statement. “When significant violations are observed, MDE has an obligation to take equitable and timely enforcement action to ensure environmental accountability and to deter future violations.”