This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

More than 8,500 Marylanders have died of COVID-19 since March 2020, as the devastating novel coronavirus pandemic swept through the state and the world.

Behind every statistic, a family mourns for a loved one and copes with those losses alone, socially distanced and without healing mourning rituals.

A year into the pandemic, Maryland Matters interviewed four families about the tangible things that help them honor and remember the lives of their loved ones.

Danitza Simpson: A Kind Soul With a Heart For Others

Two pendants trimmed with gold, hang on a chain around Janier Escano’s neck. His initials wrap around the marble-sized seed, a traditional family baby gift and symbol of protection and connection to Panamanian heritage that his mother, Danitza Simpson, gave him after he was born.

The other “deer’s eye,” or ojo de venado, belonged to her. And after she died of COVID-19 in October, the 26-year-old slipped the precious reminder adorned with her initials onto the chain next to his, as a way of keeping her with him.

“Wherever I go, I travel anywhere, I have it,” he said.

Simpson died at the age of 51. She left behind her husband of 22 years, Samuel Escano, their two sons, Adonis Escano, 20, and Janier and her daughter, Christina, 27, and her granddaughter, Amalia, 10 months — a large, close-knit extended family.

But before she died, her family members say the committed advocate for children, families and immigrants sowed seeds of kindness, generosity and support in every corner of the community she touched and throughout her life.

Born in Panama in 1968, Simpson and her younger sister, Karla, moved to the United States with their mother in 1983 when they were just 14 and 13.

The girls attended Calvin Coolidge High School in Washington. The elder Simpson went on to get a bachelor’s degree from the University of the District of Columbia. Not long after college, Simpson started working for the Prince George’s Child Resource Center, where she eventually became a director for the Adelphi/Langley Park Family Support Center and stayed for more than 25 years.

The center serves around 150 families, the majority of whom are immigrants, by empowering parents through classes and support services to create healthy, nurturing environments for young children.

Her supervisor, Jennifer Iverson, said her personality was a “superpower” that helped to create “a warm, welcoming and safe environment for families of all cultures and backgrounds.”

Simpson involved her children in her work. Janier remembers helping her at a health fair every summer. Adonis remembers reading to children at the support center as early as middle school.

“She wanted them to see the kind of work that she did,” Karla Simpson said.

When the pandemic shuttered businesses and unforeseen numbers of families experienced food insecurity, Prince George’s County Councilmember Deni Taveras (D) called Simpson to orchestrate one of the county’s largest food distribution sites.

“She was somebody that was going to make it happen,” said Taveras, who called Simpson “a warrior” for the community. The site distributed around 1,500 boxes of food a week, Taveras said.

Feeding people and making sure everyone had enough to eat was a thread woven through the tapestry of Simpson’s life.

As children growing up in Panama, Karla remembers her older sister feeding others.

The sisters did not grow up wealthy, but even with what little they had, Danitza concocted a way to make sure their neighbors who had less had something to eat.

“She would gather up her pennies,” or rally a crew of children to redeem glass bottles for money to buy some chicken and rice, said Karla. Then, she would prepare a cocinaito — a metal grill balanced on two rocks over a wood fire — and cook lunch for the neighborhood children while all the parents were at work.

“She was always the leader, she knew just what to do,” said Karla, 51, who is still grappling with the loss of her gregarious, big-hearted sister.

Simpson generously cooked for others throughout her life. No one can come close to their mother’s Panamanian-style rice with chicken, or her empanadas, said Adonis and Janier.

She gave everyone in the family a cookbook with recipes, so that someday they could make her moro or yucca, said her niece and goddaughter, Sierra Wanzer.

Simpson submerged the next generation in their Panamanian heritage, taking them to Panamanian festivals in D.C. and as far away as New York.

“We grew up very proud Panamanians,” said Wanzer, who will remember her aunt for this gift. “You couldn’t tell us that we weren’t from Panama, even though we were born here.”

Her aunt’s recipes and her “vibrant” and “bright” personality were the centerpieces of any family event, according to Wanzer.

“She would get everyone dancing, laughing,” said Wanzer, who remembers the way Simpson would enter a room playfully imitating a model on a catwalk with “absolute confidence” and announce to everyone: “The most beautiful has arrived.”

“You knew you were going to have a good time,” Wanzer said.

Months after her death, Wanzer, Adonis and Janier are still taking in the breadth of the garden Simpson planted in their community. But they’re not surprised because they watched it grow.

They saw Simpson deliver a meal to someone no one else knew needed help. They remember her getting the whole family to order food from a new business, holding diaper drives, sitting with children while their parents learned English.

“Her heart was bigger than the community,” said Wanzer. “It had to be bigger than the community in order to fit love and compassion — and just genuine kindness — for everybody.”

Dr. Herb Henderson: A Family Doctor and Family Man

After her husband of 24 years died of COVID-19 last May, Dr. Teresa Hanyok started using his stethoscope.

The sensitive medical device that has attended thousands of beating hearts reminds her of how Dr. Herb Henderson listened to his patients.

“He trained at a time where you sat and you let the patient talk,” she said. “And if you let them talk long enough, they’ll tell you what’s wrong with them, or they’ll give you enough clues to point you in the right direction.”

Hanyok, 53, recalled one college student who came to Henderson wanting anxiety medication. She told her family physician she feared failing a calculus class.

Instead of giving her the medicine, Henderson tutored her in calculus, Hanyok said.

“She came back afterward and thanked him not only for passing the class, but helping her get the confidence to finish up and finish college.”

Whether it’s his stethoscope at work or his musical instruments or his books at home, Henderson, who died at age 56, left behind a trail of physical things by which his family will remember him. But as Hanyok and her two children, Josie, 17, and Paul, 14, approach the one-year anniversary of his death, they must continue to navigate his absence.

“We actually haven’t had barbecue since he died because it was something we would do together,” Hanyok said.

And this April was still too soon to dye Easter eggs without him. Henderson would write puns on the dozens of dyed shells, egged on by his family’s bursts of laughter.

These family rituals “are too painful to do right now,” she said.

The three of them recently played the board game Risk together and found themselves talking about how Henderson would have played and how he would have outsmarted them.

“He always won,” Hanyok said.

In addition to his smarts and his skill, he had incredible luck. He once hit the jackpot on a Las Vegas slot machine, which prompted his family to buy him a home version. He then frequently hit the jackpot on the home version when everyone else would come up empty.

Originally from Spartanburg, South Carolina, Henderson met Hanyok while the pair were in residency at what was then called Spartanburg Regional hospital. Henderson in 1997 followed her back to her home state. They worked in separate practices at first, until about 20 years ago when Henderson and Hanyok joined forces at Manchester Family Medicine, where he saw thousands of patients over the years.

Former medical assistant and practice manager Lauren Reece said patients, who had moved as far away as Delaware, West Virginia and Florida, traveled back for routine doctor’s visits with Henderson and are feeling the loss of their practitioner.

“It’s been almost a year already, and I have patients that are just still absolutely devastated,” Reece said.

Henderson was also the medical examiner for Carroll County.

When the pandemic hit, the couple decided to keep their practice open: Closing would force patients to visit local emergency rooms with nonemergencies and increase potential exposure to the virus.

Even though the practice screened patients and masks were worn, both doctors and their daughter came down with the virus. This was early in the pandemic, back when COVID-19 tests were precious. Treatments were experimental and only available to those who had a positive COVID-19 test result. Henderson was sick for 12 days. Hoping to get treatment, he went to the hospital. He died five days later, the same day his test came back positive.

Perhaps in May, with an assurance of a safe environment, Hanyok hopes to hold the memorial for Henderson they weren’t able to have last year. She plans to have his favorite barbecue restaurant cater and to invite his favorite band, The Rogues, to play their version of “Amazing Grace.”

But for now, the void remains and Henderson’s belongings serve as insufficient fillers.

On the side of the bed where Henderson used to sleep lies the two-foot-tall brown stuffed bear, named Harry, that he bought for Hanyok back when they were dating.

Their children sleep with the quilts Hanyok’s aunt made from Henderson’s drawerfuls of souvenir T-shirts.

His guitar and his drums lie in wait; Hanyok hopes the kids will play them someday. The slot machine sits idle in the basement.

As of March 1, Hanyok sold the couple’s medical practice to a health care system, but she will continue to work there. The sale unburdens her from managing the practice on her own and gives her staff job security.

But she’ll use her husband’s stethoscope to listen to the hearts of their patients. “I don’t know what I’ll do if it breaks.”

Kevin Crabtree Sr.: A Little League Coach Who Mentored Generations

When Kevin Crabtree Sr., 58, died in December from complications due to COVID-19, he left a legacy of volunteerism and mentorship to his family and his Allegany County community.

Crabtree taught hundreds of children how to play baseball in his nearly 30 years of coaching the Oldtown Indians for the Bi-State and Hot Stove leagues.

Former player Miranda Kott played for Crabtree every season from the time she was four until she graduated high school. And for the last two seasons, the 29-year-old has helped coach her son’s Oldtown Indians teams.

She said her coach was “extremely dedicated to the team and to us kids,” and always made sure games were about sportsmanship and having fun.

But, whether it was intentional or not, Crabtree was much more than a coach. Motivated by a love of baseball and the belief that all children deserve a chance to play, he mentored children, volunteered his time, and to some, became a father figure.

“He lived for baseball,” said Diana Crabtree, his wife of 39 years, who remembers the day in the early 1990s when her husband first decided to coach Little League.

He had taken their oldest son, Kevin Jr., to try out for the team. But the coach at the time only took kids with prior experience, she said. Enough kids were cut, including their son, to make additional teams.

She remembers he came home and told her: “We’re not gonna let these kids go without playing ball.”

Crabtree’s wife said he made sure every child that wanted to play could play, even if their family couldn’t afford the fees or equipment.

“If they’d need something, we’d see that they would get it,” she said.

The youngest of Crabtree’s four children said his dad “was a one-of-a-kind person.”

“Whenever we lost my dad, I had people messaging me that I didn’t even know who they were, saying how much they love my dad and how appreciative they were for the things that he did for them,” Michael Crabtree said.

The 27-year-old, along with his older brother, will coach their sons’ tee ball team this season. He said there were dozens of children who looked to his dad as a father figure.

“He had four biological and probably about 50 that weren’t,” he said.

Caitlin Weems was one of them. She played for two seasons in elementary school for Crabtree’s team and said his family cared for her “as if I was their daughter.”

“In our small communities, when you lose a neighbor, we’re so close-knit and so tight, that it is like losing a family member,” she said.

A lifelong Allegany County resident, Crabtree grew up and always lived on top of Warrior Mountain, on a farm that’s been in his family for decades, according to his wife.

He played first base and outfield for the since-closed Oldtown High School. He spent every spare moment at the school’s ball field, said his wife, and often walked or biked the five miles to and from his parent’s house.

The high school sweethearts married the summer before her senior year of high school. But their time together was nearly cut short in 1992, when Crabtree, at 29, was diagnosed with idiopathic cardiomyopathy, or an enlarged heart.

Diana still remembers the chronology of events like it was yesterday. Doctors at Johns Hopkins could not believe he survived the chronic heart condition. They told her Crabtree’s heart was “like Jello; it would’ve went through their fingers,” she said.

Crabtree was not a candidate for a heart transplant because of a previously diagnosed seizure disorder.

So instead, the doctors performed an experimental heart surgery called cardiomyoplasty, wrapping one of his back muscles around his weakened heart. A pacemaker conditioned the back muscle to then contract in sync with the heart.

The operation was a success, and Crabtree’s case was written up in medical magazines. However, he was no longer able to meet the physical demands of his manual labor jobs and retired with a medical disability.

His heart grew stronger over the next months, and one season after his surgery — and for nearly the next 25 years — he coached the Oldtown Indians.

And the baseball-loving family didn’t waste a minute of their time together, according to Crabtree Jr.

Neighborhood friends, teammates and cousins would congregate on the Crabtree’s front lawn for “some of the most intense baseball games,” he said. The marathon games lasted for hours “until it was too dark to see the baseball.”

The home’s siding took some dents, and Diana said there are still bald spots in the grass where the bases were.

The last team her husband coached was his granddaughter Alison’s team, along with her dad, Kevin Jr.

The oldest of the Crabtrees’ four children was 10 when Kevin Sr. got sick. Now that his dad is gone, Kevin Jr. looks back with appreciation for every year and every baseball season they had together.

“I thought I was gonna grow up without a dad,” he said. “And I ended up getting an extra 30 years with him.”

Pilar Palacios Pe: A Caring Nurse and ‘Star of the Show’

Alex Pe kept the voice mails his mother had left him before she died of COVID-19. Anytime he wasn’t able to pick up, Pilar Palacios Pe would leave several messages in a row, sometimes five within 10 minutes.

“She would say the exact same phrase but she would sound more exasperated,” said the 34-year-old lawyer, smiling and laughing about the memory on a video call interview from his home in Washington, D.C.

In a sweet-toned voice, Pe reenacted what her first message would sound like.

“‘Hi Lex, it’s Mommy. Call me back. Love you. Bye,’” he said.

The next would sound more serious.

“‘Lex, Mommy. Call me back,’” Pe recalled. “Then it would be, ‘Alex, this is your mother!’”

When the final call involved his full name “Alexander,” he knew he would have to drop everything and call her back.

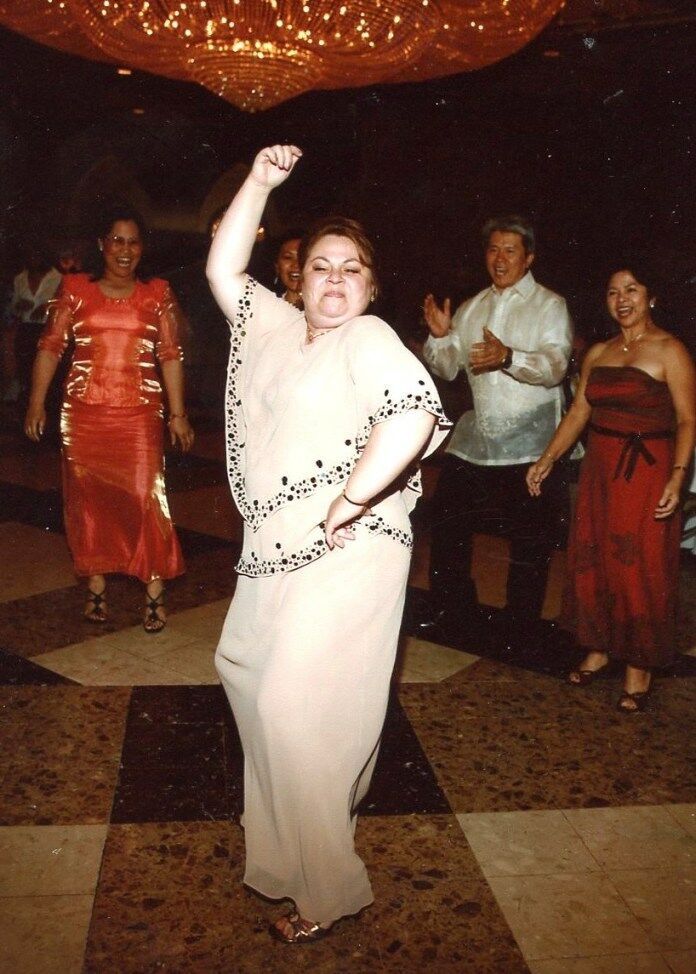

And when he did call, his mother would quickly forget the delay and laughter would soon follow. Pe said his mom was always a “hilarious comedian” with the timing of a professional stand-up comic. She loved karaoke and was known to dance whenever the mood struck her, even in public.

Those voicemail messages that used to evoke annoyance from Pe, have become precious keepsakes he will save. But since his mother died at age 63 last May, he hasn’t been able to go back and listen to them.

Also remembering Pe through digital recordings is her older sister, Maria Luisa “Lulut” Palacios Chan. The 67-year-old says re-watching the hundreds of videos she made of her sister’s comedic antics keeps her alive.

“It’s like I’m going to the Kennedy Center or some bar; Pilar is the star of the show,” she said.

Chan started making the video recordings of the sisters’ weekly visit at Pe’s home to send back to family still living in the Philippines. She would drive from her home in Woodbridge, Virginia, and Pe always made the drive worthwhile.

“She’ll start baking, mixing all the ingredients and dancing while doing it, dancing and singing,” Chan said. The sisters would drink coffee all day, tell stories and laugh, while indulging in their shared favorite — chiffon cake. And to get Chan to stay longer, Pe would start making their favorite Filipino noodle dishes.

Although she’s grateful for the technology that allows her to relive their visits, they’re a weak substitute for the gregarious sister she’s lost.

Pe’s life began thousands of miles away from her Charles County home in Nanjemoy where the sisters met each week.

She was born the eighth of nine children in 1956 in Lagao, Philippines. Her family split their time between a home in the city and a cattle ranch.

Pe moved to New York City in her mid-twenties, where she lived with her brother before marrying her husband in 1983 and moving to Maryland.

A few years after she had her first child, she earned an undergraduate degree from the College of Southern Maryland and worked at Adventist HealthCare Fort Washington Medical Center in Prince George’s County for about 20 years, her son estimated.

“She was definitely meant to be in medicine. She loved what she did,” her eldest said.

Pilar contracted the virus early last April. She went to a hospital after she had trouble breathing and fought the virus for over a month. She died in the hospital as family members from all over the world sang to her and prayed over a video call, her sister said.

Pe leaves behind her husband of 37 years, Odirolf Pe. They raised their two sons — Alex and Nicholas, 22, who is a senior in college — on their farm.

Her oldest son said the days after his mother’s death were “surreal,” especially because just prior to getting sick “she was just full of her normal self.”

Funeral attendance restrictions last spring complicated his mourning process and he felt the absence of a post-funeral gathering with friends and family to tell stories and share memories of his mom.

“That part of the ritual was missing,” he said.

Pe will continue to heal on his own schedule, he said. “There’s no rule book to this.”