This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This article was written by WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters and republished with permission. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

Members of Congress from Maryland and Pennsylvania vowed on Tuesday to force the U.S. Army to “right a historical wrong” by bestowing the Medal of Honor on a doctor who saved countless lives during the D-Day invasion of Normandy during World War II.

Cpl. Waverly B. Woodson Jr., then a medic, was heralded as a hero when accounts of his bravery and service circulated back home. But because he was African American, the military did not honor him as it should have, sponsors of new bipartisan legislation alleged.

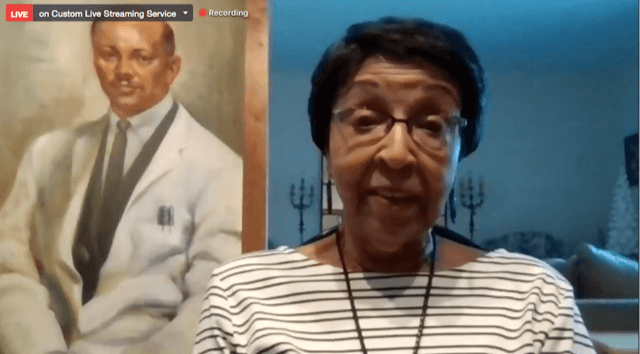

His widow, Joann Woodson, and scholars familiar with his battlefield heroics, have fueled a years-long push to get the Department of Defense to view his actions as deserving of the nation’s highest military honor.

“He was denied that Medal of Honor because of the color of his skin,” Sen. Chris Van Hollen, a Democrat from Maryland, told reporters. “It is time that we right this wrong.”

Many of the Army’s personnel records were destroyed in a fire in 1973. But the bill Van Hollen and other lawmakers have introduced would bestow the Medal of Honor on Woodson, a physician from Clarksburg, in Montgomery County, based on the evidence that has survived.

Also, a letter to President Trump from Van Hollen and Rep. David J. Trone, who represents Joann Woodson in the U.S. House, urges him to get involved in the issue.

Woodson was a 21-year-old medic in the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, the only all-Black unit that was part of the D-Day invasion. His craft was hit by a German mine near the beach, but he made it ashore with shrapnel in his groin and back, according to Army Times.

Woodson then set up a medical tent and spent 30 hours treating wounded soldiers — removing bullets, cleaning wounds, resetting broken bones, even performing an amputation — until he collapsed from his own injuries.

More than 4,400 Allied personnel died at Normandy. If not for Woodson’s actions, “dozens, if not hundreds more” would have perished, Van Hollen said.

‘We’re here to correct a wrong’

Trone told reporters that this year’s focus on “systemic racism” has added momentum to the push to more fully recognize Woodson’s service.

“We’re here to correct a wrong,” he said. “These strides we’re taking are to honor a World War II hero for incredible bravery and dignity.”

Rep. Anthony G. Brown, a Democrat from Maryland who is vice chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, said Woodson and his family “have had to wait for far too long for his due honors.”

“Now is a day of reckoning for all of us to step forward and say how do we correct the historical record,” Brown said. “And how do we ensure that going forward, we live in a nation where — regardless of race and ethnicity — everyone has an equal opportunity and everyone is recognized?”

Waverly Woodson received the Bronze Star for his actions. But after the discovery of additional documents, Joann Woodson began to press the Army to act.

Journalist Linda Hervieux, author of “Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, At Home and At War,” uncovered correspondence showing that Woodson’s commanding officer had recommended him for the Distinguished Service Cross — the second-highest military award — but that the office of Gen. John C. H. Lee believed he had earned an even more distinguished award: the Medal of Honor.

In denying Woodson that honor, Hervieux said, the military is ignoring significant evidence of his heroism, including its own press release from the time.

“Waverly Woodson was a huge star in his day,” she said. “He was called ‘#1 invasion hero.’ And there were many, many people — in the Black press and beyond — of their day pushing for the Medal of Honor.”

“We can still do something,” she added.

A lack of recognition

Joann Woodson told reporters that her husband, who died in 2005, viewed his actions in Normandy as part of his duty to his country. She said the casting in the movie “Saving Private Ryan” appeared to bother him more than his own lack of recognition.

“He was so surprised that everybody that saw [the movie] came away thinking that there really weren’t any Black soldiers on D-Day,” she said. “Everybody looked at ‘Private Ryan,’ they thought it was just all-white out there. … I did hear him talk about the injustice of not recognizing the Black soldiers on D-Day.”

Joann Woodson said her husband was dedicated to his employer of nearly 40 years, the National Institutes of Health. But she described another instance of racism that he encountered.

After he returned to the U.S., Cpl. Woodson was assigned to teach anatomy at a base in Georgia. “When he get there, they found out he was a Black military man,” she said. “And as he told me, no way would he be able to be the instructor in the South at that time.”

“So they put him on the train and sent him back to Washington and sent him to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center — and put him in charge of the morgue.”

Woodson grew up in Lincoln, Pennsylvania, and Sen. Pat Toomey, a Republican from that state, is among dozens of lawmakers sponsoring the legislation in his honor.

(Disclosure: The David and June Trone Family Foundation is a financial supporter of Maryland Matters.)