This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan’s proposal to widen Interstates 270 and 495 in Prince George’s and Montgomery counties is not getting a lot of love from The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission.

The commission staffers said a draft environmental impact statement released last week fails to properly analyze impacts on low-income communities, understates the loss of parks and cultural sites, and neglects to account for current and future stormwater runoff.

They also faulted the state for not connecting proposed “express toll” lanes to the University of Maryland Medical Center now under construction in Largo. The panel’s chairman said the environmental impact statement undercut a long-held pledge from Hogan.

Hogan wants to use a public-private partnership in which a consortium of large international firms would finance, build and maintain the new lanes for decades in exchange for the right to set and collect tolls on them. All existing lanes on the highways would remain free.

While the commissioners listening to the presentation agreed with all of the issues cited, they had a bigger one of their own.

“When are we going to talk about money?” asked Montgomery County Commissioner Natali Fani-Gonzalez.

She is worried that the counties are going to be hit with a big bill to pay for the project.

“We have millions of people under unemployment, and now we’re thinking about paying for this project? I’m not going to be stuck with this deal. My generation and my children? This is dead before arrival. It’s not OK,” Fani-Gonzalez said.

Montgomery County Planning Board Chair Casey Anderson echoed those concerns.

Anderson said the draft impact statement significantly undercuts Hogan’s oft-repeated pledge that the $9.6 billion project can be built without taxpayer subsidy or risk.

“The draft shows that it will be difficult or impossible for this project to be delivered without a significant source of revenue beyond tolls,” he said.

Anderson noted that the governor has promised to provide money generated by the project to counties in the Washington, D.C., region to improve transit service.

He said potential litigation, a spike in cost of materials and the potential need to relocate underground water pipes could add significantly to the project’s cost.

“Nobody in Montgomery County or Prince George’s wants to be stuck with the bill for a project that experiences cost growth beyond what can be covered by tolls,” he added.

In a statement, Transportation Secretary Gregory Slater conceded that some portions of the multi-part project may not make money and will need “gap funding.” He did not identify the source of those funds.

On balance, the state will not be subsidizing the project, he said.

“For the study outlined in the DEIS includes multiple projects implemented over multiple years at different times, you have to account for the differences in market conditions that will determine the cost of construction and financing at the actual time of construction for each particular phase,” he said.

“In a NEPA document like this that includes multiple construction projects, you do that by showing the variances in those conditions with a range. As outlined early on, some sections will be profitable and some will need gap funding. The state remains committed to delivering this critical infrastructure project at no net cost to the state.”

After Hogan unveiled plans to use a public private partnership to widen I-270, the Beltway and the Baltimore-Washington Parkway (later dropped) in 2017, polls showed support for the idea. But that was before another high-profile “P3,” the Purple Line, became enmeshed in a contractual stalemate that threatens to bring work to a standstill.

Other concerns fell into several other broad categories:

Environmental justice

Planners said federal environmental law requires the Maryland Department of Transportation to assess a project’s impact on low-income neighborhoods and communities of color so that mitigation can be included.

“Data has been collected, however the analysis has not been done,” said Debra Borden, the lead Prince George’s County planner for the project. “The analysis should look at air/noise/water pollution, hazardous waste, aesthetic value [and] community cohesion, which is very important because the Beltway has already bisected some of these communities in the past.”

“Because the analysis has not been done, we can’t even talk about what mitigation strategies we might want to see in those areas,” she added.

Borden said state officials have told local planners they intend to conduct that analysis after they select their final design. “That’s too late,” she told the panel. “These are our communities. To say that we are not happy about the lack of analysis in this area is an understatement.”

Borden said her comments applied to both counties through which the project would be built, but she noted that 90% of the affected communities in Prince George’s are low income or majority-minority and therefore “qualify for this kind of mitigation and community benefits discussion.”

“We want to get to that discussion sooner rather than later, and shoehorning it in at the end of the discussion is not really appropriate.”

MNCPPC General Counsel Adrian Gardner, who described himself as a “proud son” of Glenarden, a community that was divided by the completion of the Beltway in the 1960s, echoed Borden’s comments.

“By not doing this analysis now, you’re going to exacerbate a problem that really started a long time ago,” he said.

Impact on parks and cultural features

Planners said the state’s tentative plans would require 31 acres of parkland — 24 from Montgomery and seven from Prince George’s.

They said the project’s “limits of disturbance” — the areas near the existing roads that will need to be taken to construct on-and-off ramps, primarily — have been understated.

They also said that numerous cultural, historical and archaeological sites haven’t been properly cataloged. They include cemeteries (including some where slaves are buried), parks, and historic housing.

“We’re concerned that they’re showing a very conservative area,” said Jennifer Stabler, the Prince George’s Planning Department’s archaeologist. “They saying that they’re not going to tear any houses down, but I can’t imagine that they will not have to do that. Some of the houses are very close to the current Beltway.”

Montgomery County Parks Cultural Resources supervisor Joey Lampl said “critical archaeological evaluations and boundaries for significant historic sites” are missing.

“We cannot properly assess the impact of the project upon these resources if they are not fully evaluated,” she said.

Lampl said her agency anticipates calling in the federal Advisory Council on Historic Preservation to mediate the county’s dispute with the state, “to assist us in getting the full and proper identification, assessment and mitigation.”

Stormwater runoff warnings

Planners found fault with the state’s plan for addressing existing and future stormwater runoff adjacent to the two roads.

“It completely ignores the decades of degradation that the existing highways have inflicted on our local land,” said Erin McCardle, a Montgomery Parks engineer.

“The hundreds of acres of new impervious surfaces that they propose for off-site treatment… is completely unacceptable. It will not adequately protect our downstream resources and our downstream infrastructure.”

McCardle called on MDOT to go beyond “the bare minimum” required by statute, and for any new commitment to be incorporated in writing in all future decisions and documents. “This is the best opportunity they will ever get to address some of these issues.”

She said if the state doesn’t force the concessionaire to address the issue when building the new lanes, “it’s going to come at a high cost to local governments and local taxpayers” in the future.

In a statement, MDOT spokesman Terry Owens said the DEIS was developed “in cooperation” with Maryland’s local and federal partners and that it “complies with all federal requirements including the Community Effects Assessment and Environmental Justice Analysis.”

He said the state values its relationship with M-NCPPC and will review all comments received prior to the agency’s work on the Final Environment Impact Statement. The project will “deliver improvements for the quality of life Marylanders including a new American Legion Bridge for the National Capital Region and infrastructure improvements to reduce congestion that would take decades to deliver without a P3 solution.”

Access to Prince George’s Hospital

Commissioners and planning staff renewed their push for improved access for toll lane drivers whose destination is the new UMMS facility under construction in Largo.

The current plan includes an exit for northbound drivers at Landover Road (Route 202) and a southbound off-ramp at Central Avenue (Route 214). Those exits were added in response to earlier pleas from county leaders.

But on Wednesday planners insisted that the facility deserves full access at both exits, so motorists don’t have to drive past the hospital and then backtrack on local roads.

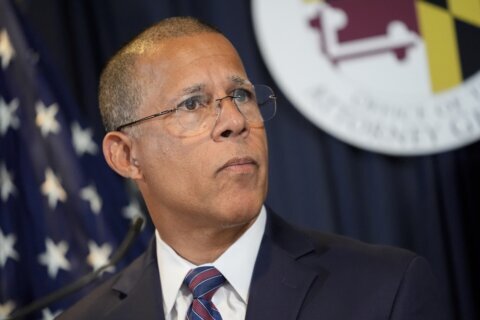

“This is so key to Prince George’s County,” said M-NCPPC Vice Chairwoman Elizabeth Hewlett. “For me that’s just non-negotiable.”

MDOT’s Owens said the state has provided “direct access locations to the managed lanes at multiple interchanges to serve traffic in the region.”

“Interchange access locations at MD 202 and MD 214 may serve traffic for the hospital,” he added.

The release of the DEIS on July 10 begins a 90-day public comment period that includes four virtual town halls in August and two in-person events in September, one in each county.

The planning commission’s views on the project are potentially crucial to the project. Under the Capper-Cramton Act, a 90-year-old law used to acquire land for the construction of the George Washington Parkway, the state can only obtain M-NCPPC parcels that were transferred from the federal government with the agency’s approval.

WTOP’s Michelle Murillo contributed to this report.