ANNAPOLIS, Md. — Two bills stemming from recent cases of child abuse in Maryland are making their way through the state legislature, which would hold mandatory reporters — those who have to report suspected child abuse by law — accountable when it comes to preserving and protecting children.

The first bill, more than a decade in the making, would assign a $1,000 fine and six months in prison for professionals such as teachers and social workers who have actual knowledge of child neglect or abuse and fail to report it.

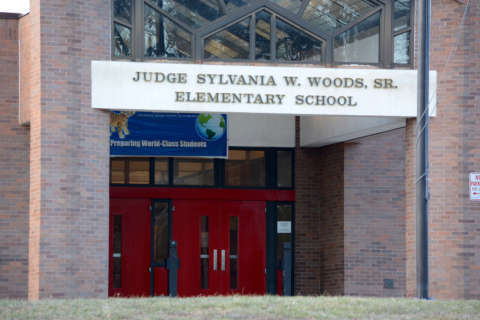

Testifying in front of the House Judiciary Committee, Prince George’s County State’s Attorney Angela Alsobrooks reminded delegates about the case of convicted child predator Deonte Carraway, who is serving more than 100 years in prison for the abuse of 23 children both on and off school grounds when he worked as a teacher’s aide and volunteer.

Court documents said multiple educators, including the principal, knew of Carraway’s inappropriate and familiar behavior with the children, as well as the potential for abuse, and did not report it.

“In the Carraway case, it would have given us penalties if we would have discovered that someone in that line knew about the abuse and allowed it to continue without calling. In that case, we would have had at least the penalties associated with the law to hold people accountable,” Alsobrooks said.

Montgomery County Del. Kathleen Dumais questioned why the penalty of losing a teaching certification was not a strong enough penalty. “If you take their license away, I think that would send a message,” Dumais said in the hearing.

“The parents would probably disagree. They think more should be done,” Alsobrooks responded. The American Academy of Pediatrics supports the bill, which is a first for the many times it has reached this phase in different iterations.

However, some feel it is unfairly targeting teachers and those who have devoted their careers to children.

“The majority of teachers go to school every day to care for children. We are talking about the minority of cases where something happens that is egregious,” Alsobrooks said of the proposed penalties.

The bill is the result of years of compromises between opposing parties, both sides have said. And while it is closer now to becoming law, child advocate Ellen Mugman said it lacks specificity in the defining of “actual knowledge” and in excluding mandatory reporters from any penalty after the victim has reached adulthood.

The second bill Alsobrooks was advocating for in Annapolis is in the Maryland Senate and posed this question to lawmakers: Is a law needed to require someone to check on a child’s welfare after a parent threatens them?

In two separate cases, Alsobrooks said three children lost their lives because their parents, who were mentally unstable, were left in charge of their care after making threats against their life.

“It just really closes a loophole for us and requires the Department of Social Services to go in and do a welfare check on a child when a parent makes a threat against a child,” Alsobrooks said.

Vanita Taylor, of the Maryland Office of the Public Defender, said the legislation is unnecessary and would strip professional caretakers and responders of their discretion. Testifying in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee, she said that the law could also lead to false reporting if someone called in anonymously to report child abuse that was not happening.