As part of Women’s History Month, WTOP explores the story of one Food and Drug Administration medical officer who persisted in asking questions and prevented more mothers from taking a drug that could harm their babies.

When she asked why she did not have any hands, the answer Leslie Mink, of Silver Spring, Maryland, got was God wanted her that way.

Paul Koneczny, of Christiansburg, Virginia, figured it was just “bad luck” that he did not have a working elbow on his right arm. It was just something that happened and he didn’t know how.

Mink and Koneczny are two of several dozens in the U.S. whose birth defects were similar to those linked to a drug called thalidomide that some pregnant women took during the 1950s and 1960s.

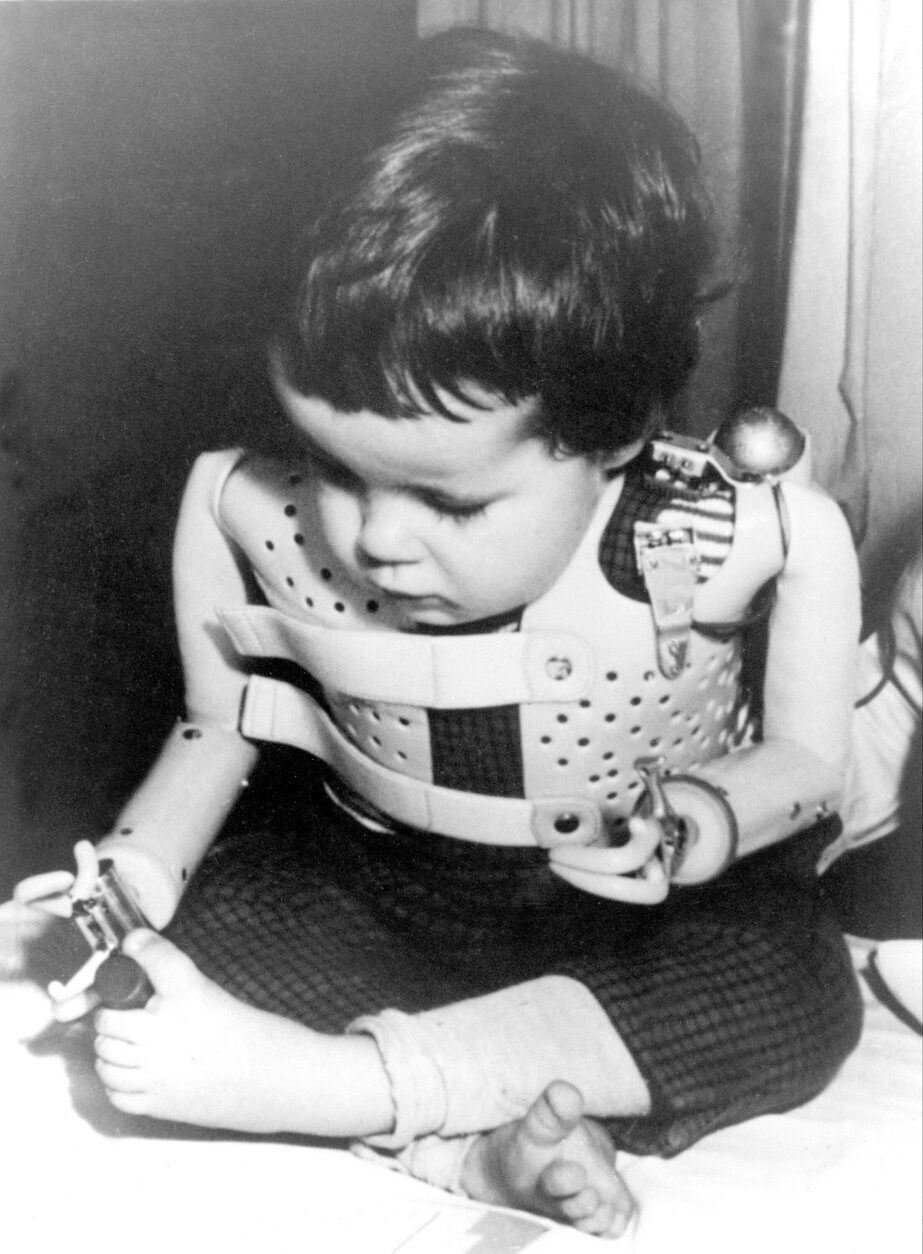

Some of the babies that were born exhibited a rare congenital anomaly called phocomelia — where upper or lower limbs are shortened or missing so that feet or hands are closer to the body.

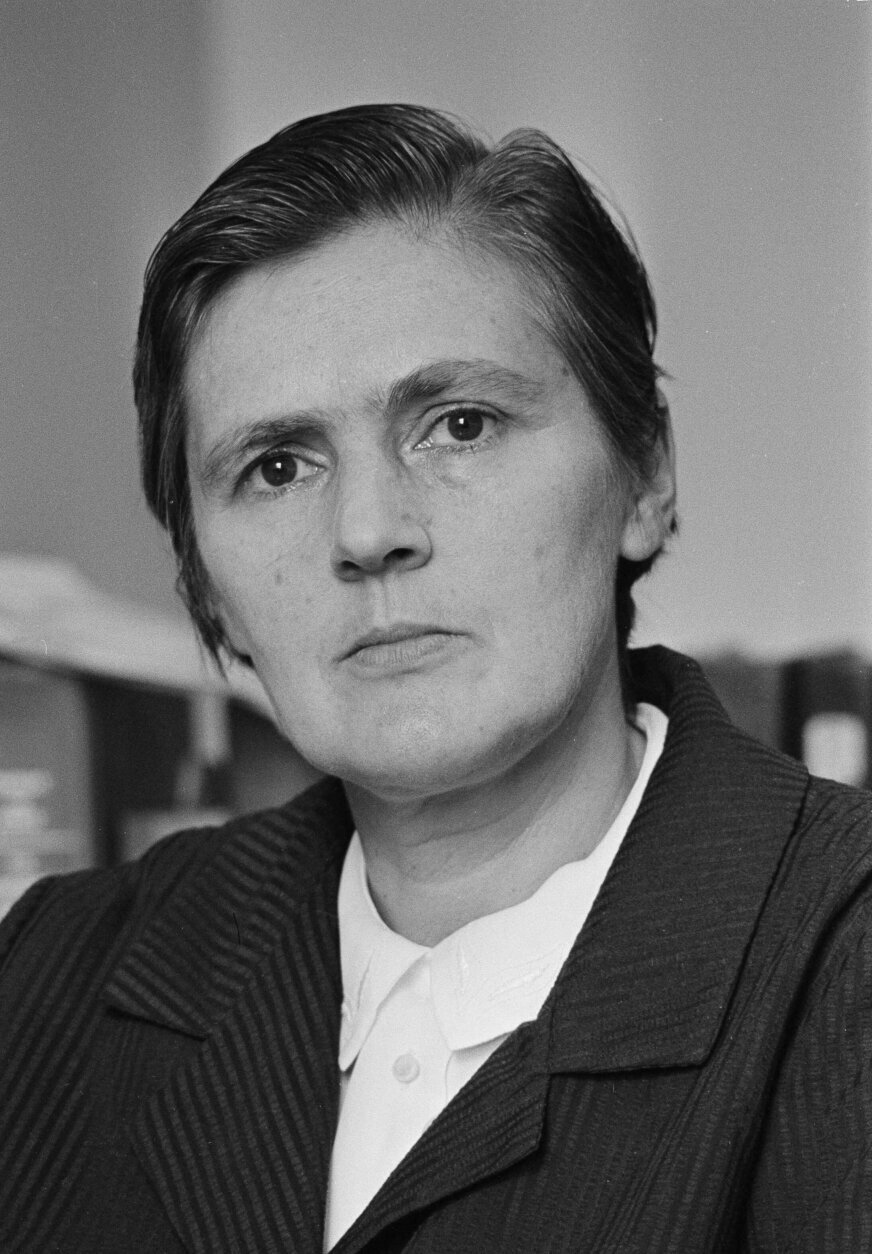

It’s a small number compared to the thousands born with birth defects in Germany, England, Canada and Australia, where the drug had been on the market for several years before its U.S. application reached the desk of Dr. Frances O. Kelsey, a medical officer with the Food and Drug Administration.

It was one of the first drug applications that Kelsey had to review as part of a job she had just started in 1960. But she was up to the task, said FDA historian Dr. John Swann.

Kelsey had a doctorate in pharmacology and a medical degree from the University of Chicago. She was a faculty member in the pharmacology department at the University of South Dakota and a practicing doctor. Among the few full-time medical officers at the FDA in 1960, she was the only woman.

A ‘very easy’ drug to approve

The German firm Chemie Grünenthal, which had acquired thalidomide, licensed it to American firm Richardson-Merrell, which then submitted a new drug application in the U.S. under the brand name Kevadon.

While thalidomide was used as a sedative, it was also often prescribed to pregnant women to address morning sickness. It was widely distributed and when it came on the market in Germany, it was even offered as an over-the-counter drug, Swann said.

U.S. law at the time required that all new drugs must be shown to be safe for use in order to go on the market. The FDA then had 60 days to review the application. If more information was needed, the clock could be reset. That happened several times in the thalidomide application, Swann said, because Kelsey kept asking for evidence to show that it was safe.

The so-called evidence that had been supplied relied on testimonials or references to show how it was used in other countries, and, “that’s not what Dr. Kelsey was looking for under the law. She needed evidence, for example, of its long-term toxicity, since sedatives often are used over the long-term,” Swann said.

“On 25 May 1961, I wrote a letter to Dr. Murray (contact man for Richardson-Merrell) expressing concern that evidence of neurological toxicity apparently was known to Merrell without being forthrightly disclosed in the application. I think Dr. Murray was rather upset at receiving this letter. He thought it was slightly libelous.” — Dr. Frances Kelsey, “Autobiographical Reflections”

Kelsey and her team of experts continued to ask for more evidence, data and clarification, which surprised officials at Richardson-Merrell.

“They were expecting this to be a pretty easy call. Well, Dr. Kelsey had other ideas,” Swann said.

“I came on the first of August 1960 and I think I got the thalidomide application in early September 1960. I believe it was the second one that was given to me. I was the newest person there and pretty green, so my supervisors decided, ‘Well, this is a very easy one. There will be no problems with sleeping pills.’” — Dr. Frances Kelsey, “Autobiographical Reflections”

A year later, researchers in Germany and Australia linked the drug to “to clusters of rare, severe birth defects — hands and feet projecting directly from the shoulders and hips — that eventually were shown to involve thousands of babies,” according to the FDA website, describing the impact of what could have happened in the U.S. as a “near disaster.”

“Here was a drug that given for three or four months could cause severe neuropathy. With thalidomide, a growing infant might, perhaps, be exposed to it for five or six or up to nine months. This was the sort of drug that was taken as a mild sedative/hypnotic, and the mother might take it a lot during pregnancy. I do not know exactly what the genesis of this concern was. But I think it was the fact that this was something we were thinking about in terms of all drugs, due to other recent examples. It was in the setting; it was really a new thing — this concern about safety of drugs and childhood. — Dr. Frances Kelsey, “Autobiographical Reflections”

‘(My mother) carried a ton of guilt’

Thalidomide was never approved in the U.S., but it was allowed to be distributed to some physicians for “investigational purposes.” However, oversight of clinical investigations at this time was not terribly strict, Swann said.

The FDA initially believed there were just a few dozen physician investigators, but it turned out to be much more.

“How they were distributing the drug turned out to be much more cavalier than the agency was aware of,” Swann said.

Koneczny’s mother did not get the pill from a doctor, but from a colleague. Koneczny, who’s in his 60s, said his mother was having horrible nausea during her first trimester. She took just one pill, didn’t like the effect and stopped taking it.

“It was only a single pill. But the effect that it had …” Koneczny said. The bone in his right forearm did not grow. He does not have a working elbow on his right arm, which he said just hangs all the way to a fully functional hand, “But I just have one bone.”

Koneczny had an inkling years before he had a conversation with his mother that his arm may be attributed to thalidomide after a doctor told him about the drug and how it was circulating around the time he was born.

“My mom never really talked about it. She carried a ton of guilt,” Koneczny said. “She just felt so bad that she put me in this position for the rest of my life. … She knew she had taken a pill, but she didn’t know much about it.”

Looking for answers

Mink, of Silver Spring, has been combing records and searching for proof on whether her mother took thalidomide. Growing up, people would ask whether she was a “Thalidomide baby.”

“I would say no because my mom said no, that it was just like a fluke that happened,” Mink said. “And so that’s what I believed because she never said anything more. And nobody else in my family ever said anything.”

She hasn’t been able to obtain any records that indicate whether her mother took the drug. Since it was a sample drug, there may be no records to show that. She never asked her mother, who died when Mink was 27 years old, whether she took the drug.

“I don’t have any proof that I’m a thalidomide baby. But, I’m in the right year,” said Mink, who will turn 65 in August. “My mother either didn’t know she took it or she didn’t want to admit that she took it.”

Swann said the FDA was able to confirm 17 cases linked to the investigational drug, including five or so cases where the mother had received imported thalidomide from sources abroad. But he added that recent research indicates a lot more babies were affected than previously thought.

“Given the rarity of this kind of birth defect, one can easily be compelled by the evidence to link this to thalidomide,” Swann said. “And indeed, some of the interviews I’ve read with some of those affected certainly indicate that it was caused by thalidomide.”

‘A legend’ within the FDA

The thalidomide scandal and Kelsey’s role in preventing more women from having access to the drug were some of the catalysts in the passing of the Kefauver-Harris Amendments in 1962, which required that before marketing a drug, firms had to prove not only the safety but the effectiveness of the drug for its intended use.

The Kefauver-Harris Amendments formalized manufacturing practices, required that adverse events be reported, and transferred the regulation of prescription drug advertising from the Federal Trade Commission to the FDA.

Swann said Kelsey is a “legend” not just with the FDA.

“The stand that she took has been meaningful to everyone.”

In 1962, Kelsey was awarded the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service by President John F. Kennedy, the highest honor given to a civilian in the U.S. She was the second woman to ever receive the award.

In 2010, she was the first recipient of an award named in her honor, the Dr. Frances O. Kelsey Award for Excellence and Courage in Protecting Public Health. The award honors the work of those who have been putting public service and protection at the forefront, including most recently, those doing COVID-19-related work.

Kelsey lived in Maryland until 2014, until she moved to Canada, where she was born. She died in 2015 at age 101.

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2024 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.