From firearm legislation to focusing on mental health, two D.C.-area jurisdictions are finding different approaches to tackle the growing number of gun deaths in the region.

During Suicide Prevention Month, Fairfax County, Virginia, reported new data on its “red flag law,” while officials in nearby Montgomery County, Maryland, propose a bill designed to tackle mental health and gun violence.

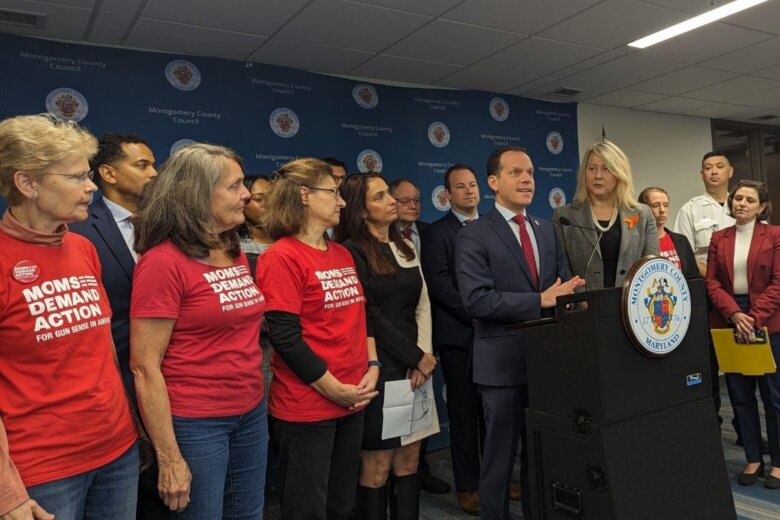

Montgomery County Council President Evan Glass introduced a bill Tuesday that would require firearms retailers to provide information on suicide prevention when firearms are sold. Glass cited statistics from the CDC indicating that 42% of all suicides in Maryland are committed with firearms.

Red flag laws allow residents to seek the help of law enforcement to remove a weapon from people who are considered a danger to themselves or others.

The intention of the Suicide and Firearms Education, or SAFE Act, “is to reduce harm by providing potentially lifesaving information when someone is purchasing a firearm or ammunition,” Glass said.

“We have had enough of thoughts and prayers, we need to act,” he added.

A similar bill passed in Anne Arundel County has been the subject of a legal challenge by Maryland Shall Issue, a Second Amendment and gun owner’s rights group. After an initial legal defeat, the group appealed the case to the U.S. Court of Appeals.

The organization has argued that forcing retailers to include the information amounts to compelled speech, a violation of the First Amendment. A hearing in the case is scheduled for December.

At Tuesday’s event in Rockville, Beata Stylianos, whose late husband, Yorgos, died by suicide in which a firearm was used, said, “My experience as a survivor has led me to this advocacy to prevent gun suicides.”

In Fairfax County, police report data on red flag laws.

Fairfax County police said in the first half of 2023, from January through June, their officers seized 111 firearms under Virginia’s “red flag” law. Sgt. Amanda Paris explained that anyone concerned that a person might harm themselves or someone else can contact police and ask for an Emergency Substantial Risk Order, or ESRO.

But under Virginia law, only police or a commonwealth’s attorney can petition a judge or magistrate for an ESRO, and they must provide probable cause that the person subject to the order poses a risk to themselves or others.

Paris said the orders are typically sought after police have responded to a call for service. If police believe that someone “wants to use a firearm to hurt themselves or hurt others,” they may seek the ESRO. She said police “will talk to victims if there are victims as well, to get a full picture” of the circumstances.

Paris told WTOP in an interview that the law doesn’t just allow police to seize weapons already in the possession of the subject of the order, but “it actually also temporarily stops them from being able to purchase firearms.”

The temporary order is for a 14-day period, and during that period, a hearing is held in circuit court.

“A judge will then determine if the order shall be a substantial risk order which can last for 180 days,” Paris said.

Virginia is one of more than 20 states, including D.C. and Maryland, that have some form of red flag laws.

There have been challenges to the emergency orders on the grounds that they violate the Second Amendment, and there have also been concerns about violation of due process.

“Our ultimate goal is to make sure that individual is safe, but also that the community is safe,” Paris said.