The recent heat wave created bathtublike temperatures in some D.C.-area waterways, and that’s not good for flora and fauna.

“One of the things we’re concerned about is physiological stress, even if it doesn’t kill an animal,” said Allison Colden, Maryland fisheries scientist for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

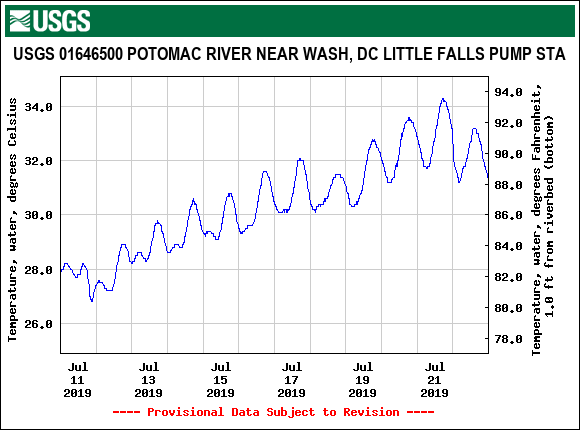

As first reported in The Washington Post, the Potomac River had a record-high temperature of 93.7 degrees on Sunday.

The Chesapeake Bay, too, has been warmer than usual. And those higher-than-usual water temperatures can foster detrimental consequences, Colden said.

“Diseases can become more prevalent when you have an animal that is already stressed and can’t fight off pathogens it would normally be able to withstand. So, this is concerning,” she said.

Higher temperatures can increase the production of algae blooms that fuel dead zones. Fish are cold-blooded and can’t adjust when water temperatures aren’t ideal. Warmer water holds less oxygen than cooler water.

“So there’s the direct impact just basically on how well animals and plants are functioning in terms of all of their metabolic functions. But also, those warming waters can hold less oxygen and make it harder to breathe,” Colden said.

Creatures looking for ideal temperatures and oxygen levels might experience “habitat squeeze” when they all crowd into the same area. When water is shallow, there may be no ideal location.

Is this the new normal?

Water temperatures have been documented to be on the rise over the past 100-plus years.

“We know that all surface waters since 1901 have warmed in the lower 48 [states],” Storm Team 4 meteorologist Amelia Draper said. “The most warmth is being shown in the North Atlantic, where up near Maine we’ve seen the warm up by about 3 degrees Fahrenheit.

Also, since 1990, stream temperatures have risen at 65% of the continental United States gauges, Draper said.

Colden noted that longer-term temperature adjustments could result in different types of creatures calling this area home.

“We may expect to actually see some species in the Bay shift their range northward,” said Colden, who observed that the same thing happening farther south may lead to new species migrating north into the Bay.

The Bay is strong

Though the Bay is being hit with the double whammy of higher temperatures and lower salinity from last year’s record rains, Colden said it’s showing good signs of resilience.

Watershed states have reduced the amount of nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment pollution being released into the Bay that used to fuel so much growth of even more pollution. The loop of that cycle is beginning to break down however, and Colden said there’s evidence the Bay is bouncing back from those challenges on its own, naturally.

That indicates efforts are “on the right path,” she said, in terms of mitigating “the stresses that (are) caused by the human side of things, while we continue to study and cope with nature’s side of things.”