WASHINGTON — This week’s release of an exhaustive study chronicling 70 years of child sexual abuse by Catholic clergy in Pennsylvania has put the Archbishop of Washington, Cardinal Donald Wuerl, under scrutiny.

The former Pittsburgh bishop’s name is mentioned roughly 200 times in the 884-page report, which details how Wuerl handled the discipline following accusations against some of the priests.

Two particular cases, which Wuerl mentions in his statement to the grand jury, serve as a study in contrasts as to how he dealt with the pervasive sexual assault scandal within the Pittsburgh diocese.

In one case, a priest was eventually removed, yet still received financial support that included a $1,000-a-month sustenance payment — even after a new victim had come forward alleging abuse. In the case of another priest, Wuerl was more aggressive, pushing to get the priest psychiatrically evaluated. Wuerl even traveled twice to the Vatican to urge the Catholic hierarchy to remove that priest from practice.

In both cases, the majority of the abuse occurred before Wuerl became bishop in 1988.

Father Richard Zula

Abuse claims against Father Richard Zula began in September 1987. The grand jury identified him as one of the “predator priests” who produced child pornography while raping children, a group that included Father George Zirwas.

Yet months later, officials were discussing returning Zula to the ministry, even after he confessed his criminal conduct.

In May 1988, not long after Wuerl took over in the diocese, a summary of facts was collected as part of a lawsuit filed by Zula’s victim and that victim’s brother, who himself had been abused by another priest.

A criminal investigation followed, and Zula was charged with more than 130 counts related to child sexual abuse. “There is no indication that the Diocese disclosed their prior knowledge of Zula’s conduct or Zula’s confession to the police or to the public,” the report said.

Amid this scandal, Wuerl authorized a confidential settlement with the victims’ family comprising a $500,000 lump sum payment and another $400,000, paid out over a period of 30 years. That settlement included a “confidentiality agreement.”

Zula pleaded guilty to only two of the counts. As he awaited sentencing, more complaints were made to the diocese, the report said:

“The caller advised that Zula had made frequent sexual advances on her son and at least two of his friends when they were 13-year-old altar boys. The mother reported that Zula asked the boys to pose like statues and attempted to tie them up using rope.“

The report found no indication that the diocese reported this to law enforcement.

“In fact, the Diocese was utilizing diocesan resources and personnel to advocate for Zula at his upcoming sentencing proceeding,” the report said. This included getting a doctor whose evaluation would find him “passive-dependent” and not likely someone to initiate sexual activity.

” … Unknowing parishioners were still actively tithing from their income without knowledge that church funds were being used to mitigate a convicted sex offender’s sentence,” the grand jury wrote.

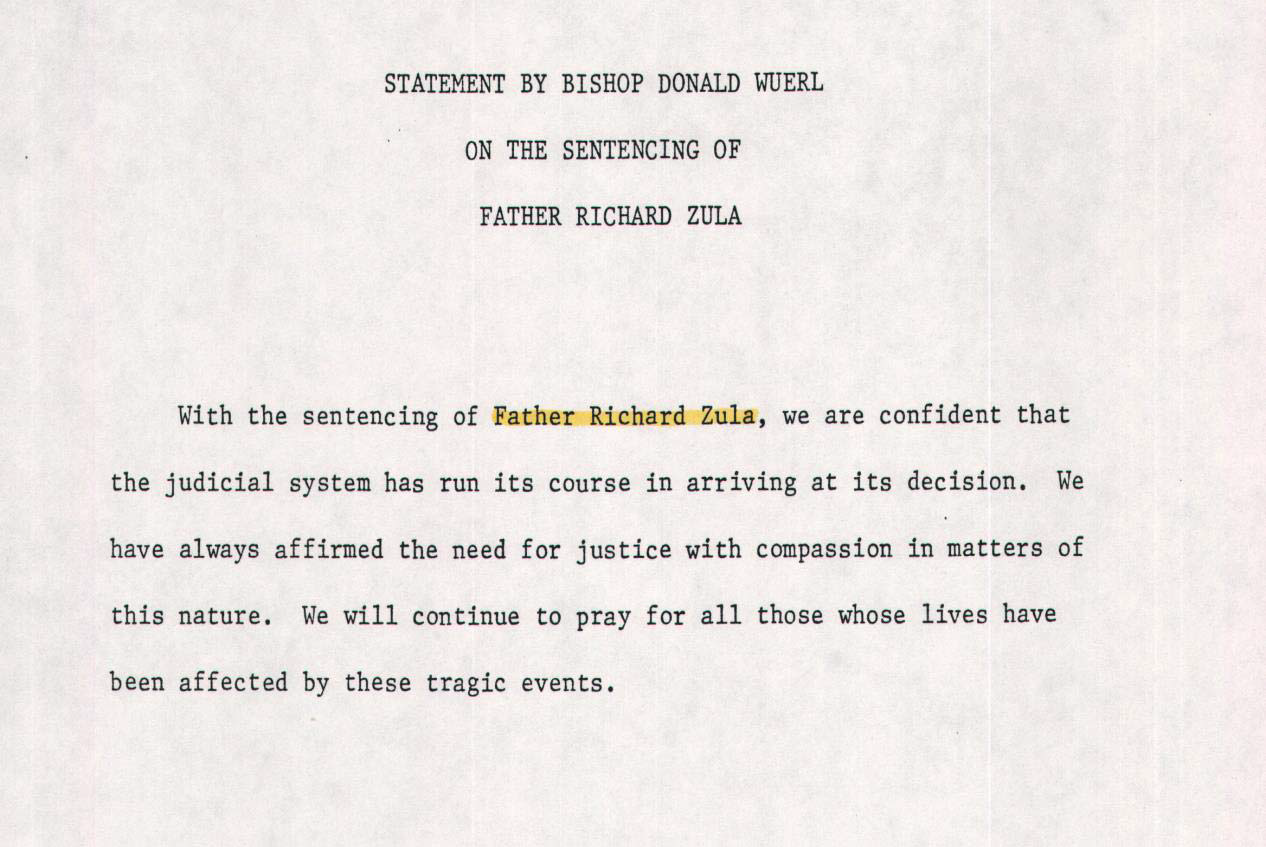

Zula was sentenced to five years in prison. A statement from Wuerl said that the system “has run its course,” according to the grand jury report. The diocese later agreed to set aside $500 for him each month until his release.

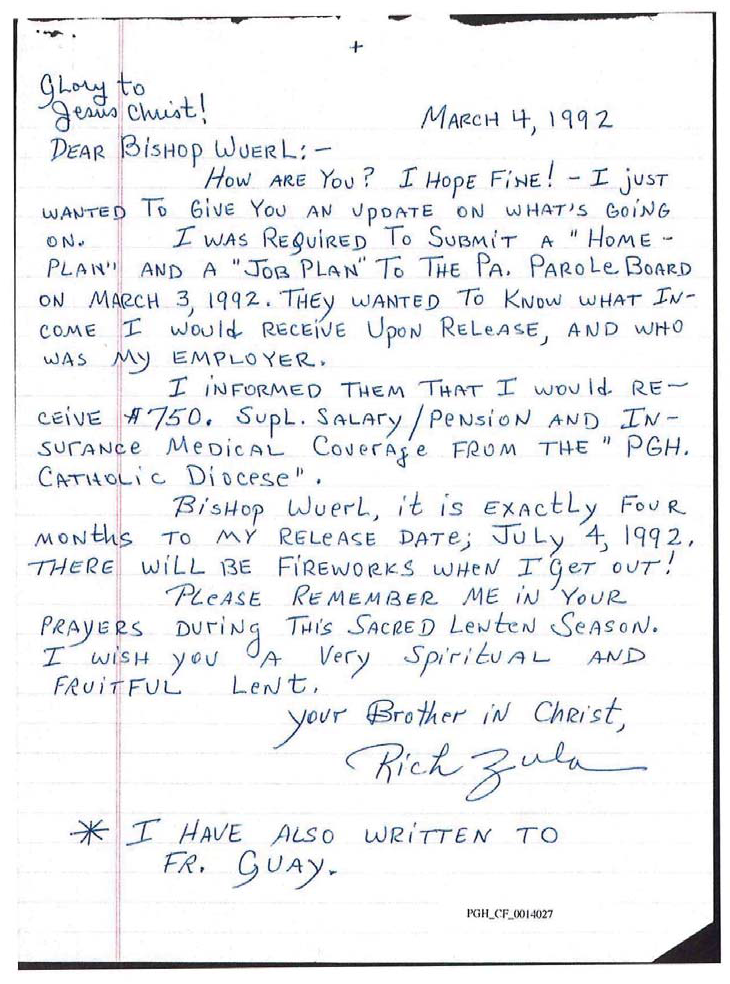

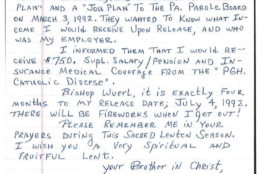

In March 1992, with Zula close to being eligible for early release, Wuerl confirmed the diocese would financially support Zula with a $11,542.68 total payment as well as $750-a-month sustenance payments.

“The Diocese continued to receive reports of past criminal conduct on the part of Zula after

his release,” the report said. After a 1993 letter to Wuerl from another victim, the diocese began removing him as a priest.

What followed were discussions in January 1995 over salary and medical benefits. “Wuerl was open” to a lump-sum payment of $180,000. Zula countered with a request for “$240,000.00 (TAX FREE).” Undated handwritten notes from a “Father Guay” include the words “slush fund — under table.”

In 1996, the diocese and Zula reached an agreement that he would resign and would still receive $750 a month as well as medical coverage.

On Jan. 31, 2001, another victim revealed abuse by Zula, yet less than 11 months later those payments were increased to $1,000 a month.

Father Anthony Cipolla

Cipolla was first accused of abuse in 1978. The victims were two brothers, ages 9 and 12. The incidents had occurred roughly a year earlier.

Criminal charges were actually filed with the Pittsburgh Police Department but were later dropped after the mother was “harassed and threatened by church officials to drop the charges and to ‘let the church handle it,'” the report said.

This intimidation included diocese lawyers aggressively interrogating the children before a preliminary hearing — which was apparently allowed by prosecutors, the mother told the grand jury writing the report.

“The attorney for the Diocese then began ‘firing questions at [the first victim and the second victim] really fast.’ The second victim “had tears in his eyes’ and the first victim ‘was just shaking like a leaf.’”

Cipolla was reassigned. Then after Wuerl took over the diocese in 1988, a third victim came forward, with similar allegations of getting a “physical” from the priest. Documents dated July 1, 1988, indicate that the diocese had done an “Internal review.” It concluded that the third victim’s allegations “were without foundation and the matter be dropped.”

Police were not informed until December 1988, when the latest victim reported it to Beaver County prosecutors.

Wuerl sent Cipolla to a psychiatric facility for evaluation, which resulted in a recommendation that he not minister to children. Cipolla sought a second opinion from a New York facility that wasn’t church-approved, from which he received a “glowing” evaluation, the report said.

Cipolla later requested to be released from the diocese. Wuerl responded that this would require a letter from the bishop in the diocese where he wanted to serve, and said he’d would have to notify that bishop about the allegations and the first diagnosis.

The priest made repeated requests to be reinstated. These were denied as he continually refused to undergo additional counseling and evaluation that the church-approved facility had recommended.

During this period of 1989—1990, Cipolla “continued to present himself as a priest in good standing despite being repeatedly warned by Wuerl to stop doing so,” the report said.

Wuerl, in 1990, “notified him that his canonical facilities had been removed because he failed to take the actions directed,” the report read. In effect, he could not be a priest until he got that church-approved evaluation.

The third victim filed a civil suit in 1992, alleging that the diocese should have known that Cipolla was a danger and that his superiors had covered it up. (It was settled out of court roughly a year later.)

In March 1993, the Vatican ruled that Wuerl was violating canon law and it ordered that Cipolla be reinstated. Weeks later, Wuerl asked the church’s Supreme Tribunal to reopen the case, even traveling to Rome in April 1993 to further his appeal.

The Vatican reversed its decision and declared Wuerl acted properly.

Yet Cipolla continued to present himself as a priest in good standing, and declined to meet with church officials, even though the diocese was providing him with a residence. In March 1996, Cipolla complained that he had stopped receiving his salary months earlier. Church officials replied that “the church had received nothing in the way of priestly ministry, service or cooperation and an increase scandal in the eyes of the community.”

Cipolla persisted, but it was all for naught: In July 2002, Wuerl asked the pope for Cipolla’s dismissal. It was issued on Sept. 19, 2002.

Wuerl: ‘I acted with diligence’

In a statement following the release of the Pennsylvania report Tuesday, Wuerl said that while the report is critical, he believes it “confirms that I acted with diligence, with concern for the victims and to prevent future acts of abuse.

“I sincerely hope that a just assessment of my actions, past and present, and my continuing commitment to the protection of children will dispel any notions otherwise made by this report,” he said.

Following the release of the report, D.C. Councilmember David Grosso, D-At Large, issued a call for Wuerl’s resignation citing the criticism of his management of priests accused of child sexual abuse in Pittsburgh.

“Child safety depends on holding institutions, not just individual perpetrators, accountable for their actions. It is for this reason that I believe Cardinal Wuerl should immediately resign,” Grosso said.

“The way he handled that, as has been spelled out in the grand jury report, was entirely inappropriate,” Grosso said. “Predators had been moved around and covered up. He should make amends for what he did.”

WTOP has reached out to Wuerl for a response.