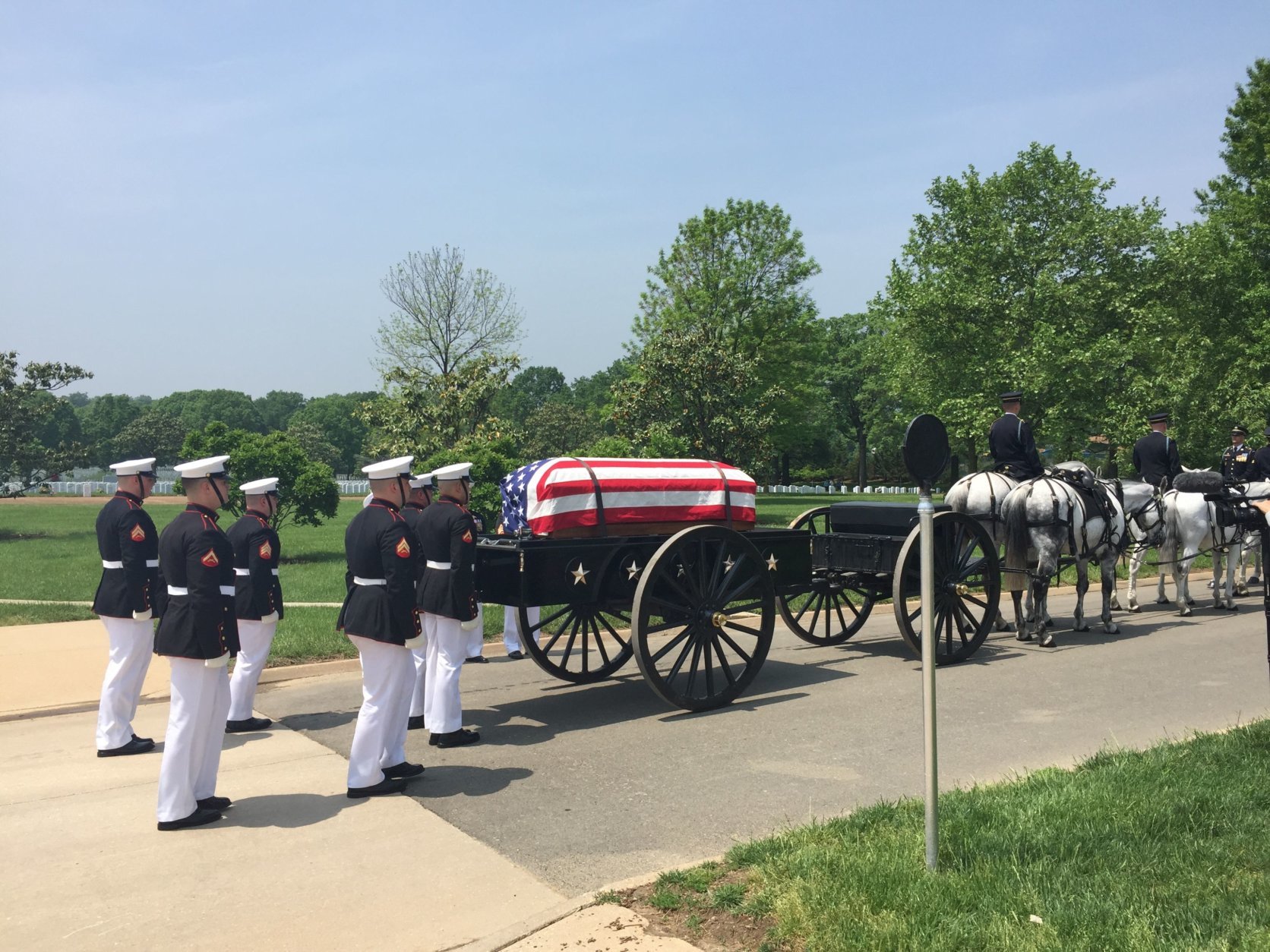

ARLINGTON, Va. — At Arlington National Cemetery, the sound of a Marine band playing the Marine Hymn grows louder as it nears a gravesite. The music is backed with the percussion of horse hooves against the asphalt road as the animals pull a carriage holding a flag-draped casket.

Inside are the remains of a brother, son and uncle who went to battle more than 70 years ago and never came home.

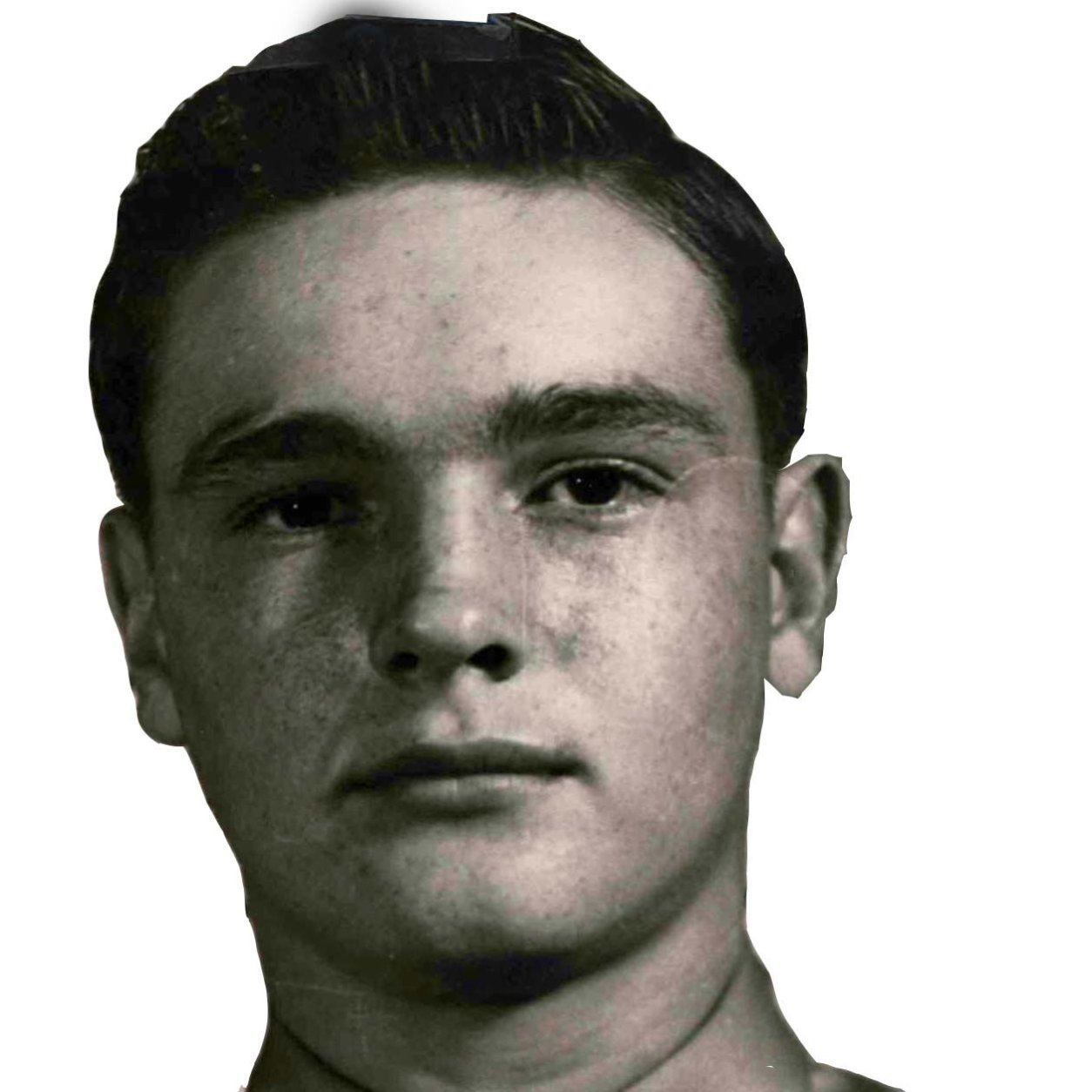

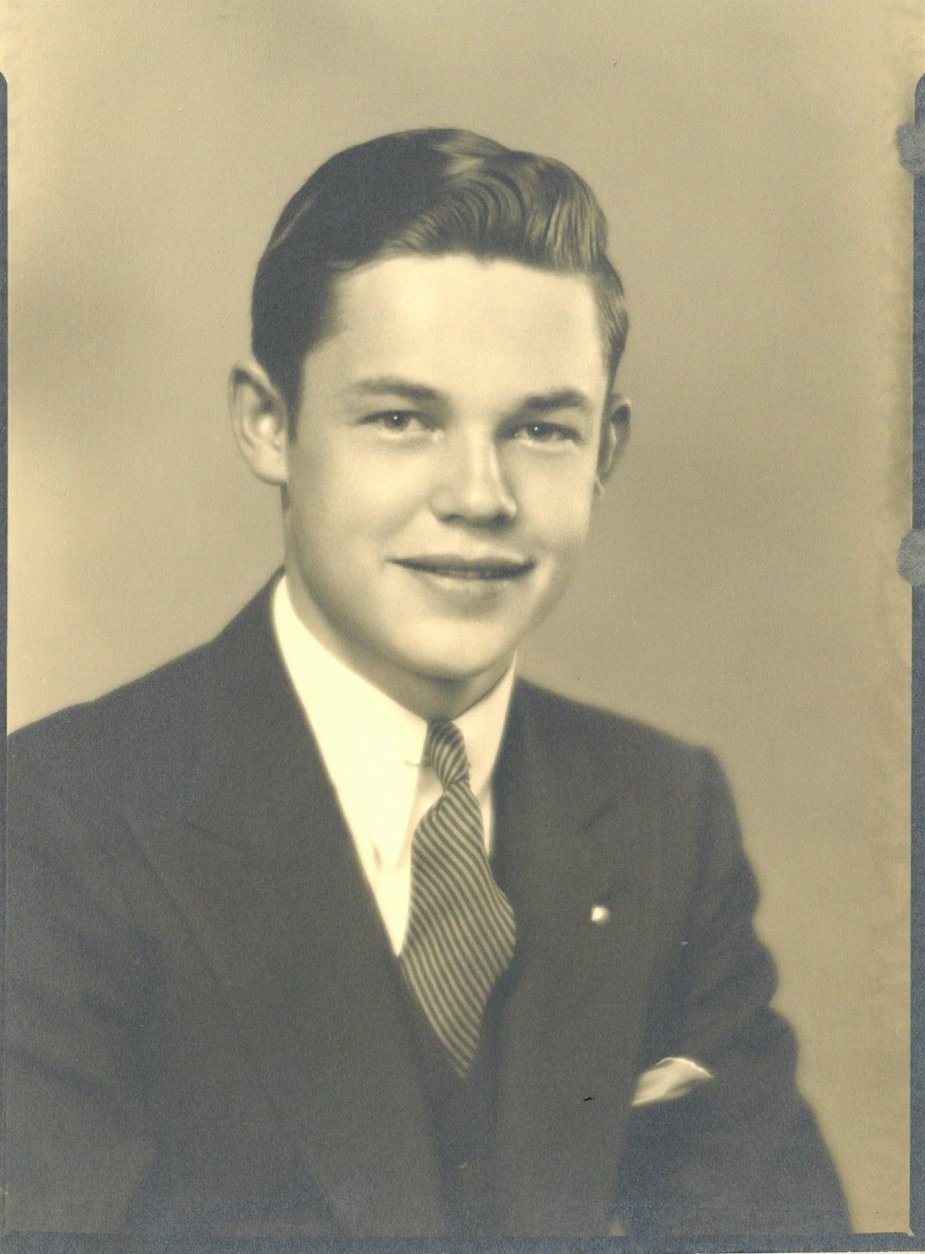

The service is for Marine Cpl. John V. McNichol, 20, of Altoona, Pennsylvania, who died Nov. 21, 1943, during the second day of the battle of Tarawa.

“Still feels a little dreamy to me,” said McNichol’s nephew, Tom McNichol. He’s one of several family members laying to rest someone they honored and loved but never knew.

During the service, McNichol’s nephew read a report of his uncle’s extraordinary heroism during the battle. Before his death, McNichol made repeated trips into enemy occupied positions, killing the occupants and destroying arms and ammunition. The recommendation for recognition said that McNichol took voluntary part in the activities, knowing that once he entered enemy positions he would be without immediate support from his comrades.

“John was the real deal; he was amazing,” Tom McNichol said after reading the report. “I wish I had known him.”

He’s one of thousands from World War II who never came home, and for years they were classified as prisoners of war or missing in action whose remains were not recoverable. But in recent years, hundreds have gotten the funerals they deserve.

Bringing the fallen home

The military has long had a program in place — Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency — which focused on finding the remains of service members lost in conflicts from Vietnam to the first Persian Gulf War, but it wasn’t until 2010 that Congress added World War II to the list.

“It’s a really nascent mission,” said Kelly McKeague, director of the DPAA.

It’s a big one: From World War II through the first Persian Gulf War, 82,000 American service members remain unaccounted for; 72,000 of those are from World War II alone.

McKeague said there’s a long process before remains can be exhumed and identified.

First, historians and researchers comb through countless files to determine whether there’s enough evidence to do a field investigation. If there is, a field investigation team is sent to examine the burial site that might be the final resting place of a service member, and interview people who may have firsthand knowledge.

If that’s fruitful, archaeologists and anthropologists are sent to examine and excavate the site. If remains are found, they are brought back to the U.S. to be identified. Scientists compare DNA from the remains to DNA samples from families of the missing.

When remains are identified, McKeague said, they are turned over to family members who are able to bury their loved ones with full military honors.

There are a lot of obstacles: Remains can be degraded by acidic soil or high water tables, or if they were dusted with formaldehyde before burial. The DPAA only has DNA samples from 6 percent of the families of loved ones unaccounted for from World War II.

Only 34,000 of those unaccounted for from all past conflicts are believed to be recoverable. The rest are called “deep sea losses,” McKeague said — bodies the military lacks the technology to find and recover.

‘This is not a fight’

John Eakin of Helotes, Texas, began a mission in the early 2000s to find his mother’s cousin, Arthur “Bud” Kelder, who died after being captured by the Japanese on Corregidor.

He had to do the research himself, pinpointing a mass grave in Manila as the final resting place of his relative. Then, Eakin said, he had to go to court for Kelder’s remains to be exhumed and identified.

He thinks keeping this mission within the Department of Defense will make the identification process take longer and cost more. He believes a civilian organization would have better expertise and more technology for the mission of bringing fallen World War II service members home.

“This is not a fight,” Eakin said; “We don’t need bullets and bombs.”

Eakin said there is enough evidence at the Manila cemetery, including a log kept by prisoners of war, to begin exhuming all graves and properly identifying the remains.

“I think these guys deserve to have their own name on a headstone, if it’s possible to do so,” Eakin said.

McKeague defended his agency’s work, and said DPAA is using the most state-of-the-art technology, when it comes to investigating and identifying remains.

He added that the military officially recognizes the Manila gravesite as the final resting place of the fallen, which means a strong case — “a 60 percent or higher threshold” — needs to be made before digging begins.

That cemetery, he said, has seen two disinterments, two exhumations and two reburials in which remains became commingled. It also has a high water table, which has led to the degradation of some remains.

That said, McKeague believes partnerships with the private sector can help the agency — and already have.

Eakin, using a burial roster and other information he gathered during and after an investigation into his fallen relative, has compiled a list of those who died at the Cabanatuan POW camp who are accounted for and others who are not. The list also contains information on where the fallen may be buried.

Recently, the archaeology programs at the University of Maryland and the University of Vienna, in Austria, teamed up to help the DPAA excavate what was believed to be the crash site of a B-24 bomber. After 40 days of digging, they discovered remains which are in the process of being tested to determine whether they are those of two crew members on the B-24.

The students “paid for the opportunity to gain experience — practical experience — and to assist the United States in this effort,” McKeague said.

Congress mandates that DPAA identify and return the remains of 200 service members to their families each year. In 2017, the agency was only able to identify and bring home 183 fallen soldiers. McKeague called the total a high water mark for the agency, and believes assistance from the private sector will help his team reach the goal of 200 this year.

An online family tree

Five years ago, Rhonda Masters, of Florida, began a search for her brother-in-law’s grandfather, who also died in the camp in Cabanatuan. She realized the military was trying to find DNA from relatives of service members believed to have died in the Philippines, and decided to get involved.

She contacted John Eakin, who was trying to find the families of those believed to be in the Manila cemetery. With his guidance, she turned to the internet for answers.

Using the website Ancestry.com, Masters said she set up profiles from some of the service members believed to have died at a POW camp in Cabanatuan, in the Philippines. One of those profiles was for Army Private Raymond Sinowitz, 25, of Brooklyn, New York.

From there, she was able to eventually find a relative of Sinowitz’s: a niece, Jan Sinowitz-Cuva, who called the online connection “amazing.”

Ultimately, a DNA sample was collected from Sinowitz’s nephew, Raymond Sims, who was named after his uncle. The DPAA positively identified remains found at the mass grave in Manila, and Sinowitz’s funeral was held at Arlington in April.

Sinowitz died in 1942 after being taken prisoner during the battle of Corregidor, in which American and Filipino service members found themselves outnumbered by the Japanese army. Sinowitz survived capture but died of malnutrition at a POW camp.

“That must have been hell on earth,” Sims said of his uncle’s last days.

Sims’ father, Albert Sims, who also served in the war, had made it his life’s mission to find and repatriate his brother. “It was a promise he made to his mother,” said Lyn Jacobs, Sinowitz’s niece and Albert Sims’ daughter. He wouldn’t live to see the day his brother’s remains would be brought home, but his children did.

“It does feel kind of nice to put a happy ending on what otherwise would have been a very unhappy and really incomplete story,” Raymond Sims said.

Masters also found relatives of another soldier who was found in the same common grave. As for her own search, the family has decided not to request that her brother-in-law’s grandfather’s remains be exhumed.

“His family is comfortable in the fact that they now know where he is,” Masters said. “Rather than disturb his remains once again, they rather that he rest in peace in the Philippines.”

Sinowitz-Cuva said closing this chapter of her family’s history brought the family closer and reconnected her with Raymond Sims, a cousin she hasn’t seen in 50 years. She calls Masters and Eakin her “angels” for helping the family bring her uncle home.

The family invited Masters to attend Sinowitz’s funeral.

“There is a special place in Heaven for people like Rhonda,” said Raymond Sims.

For people looking for loved ones who did not return from World War II, McKeague encourages contacting the DPAA and providing information and DNA which can help build their database for identifying those unaccounted for from the war.