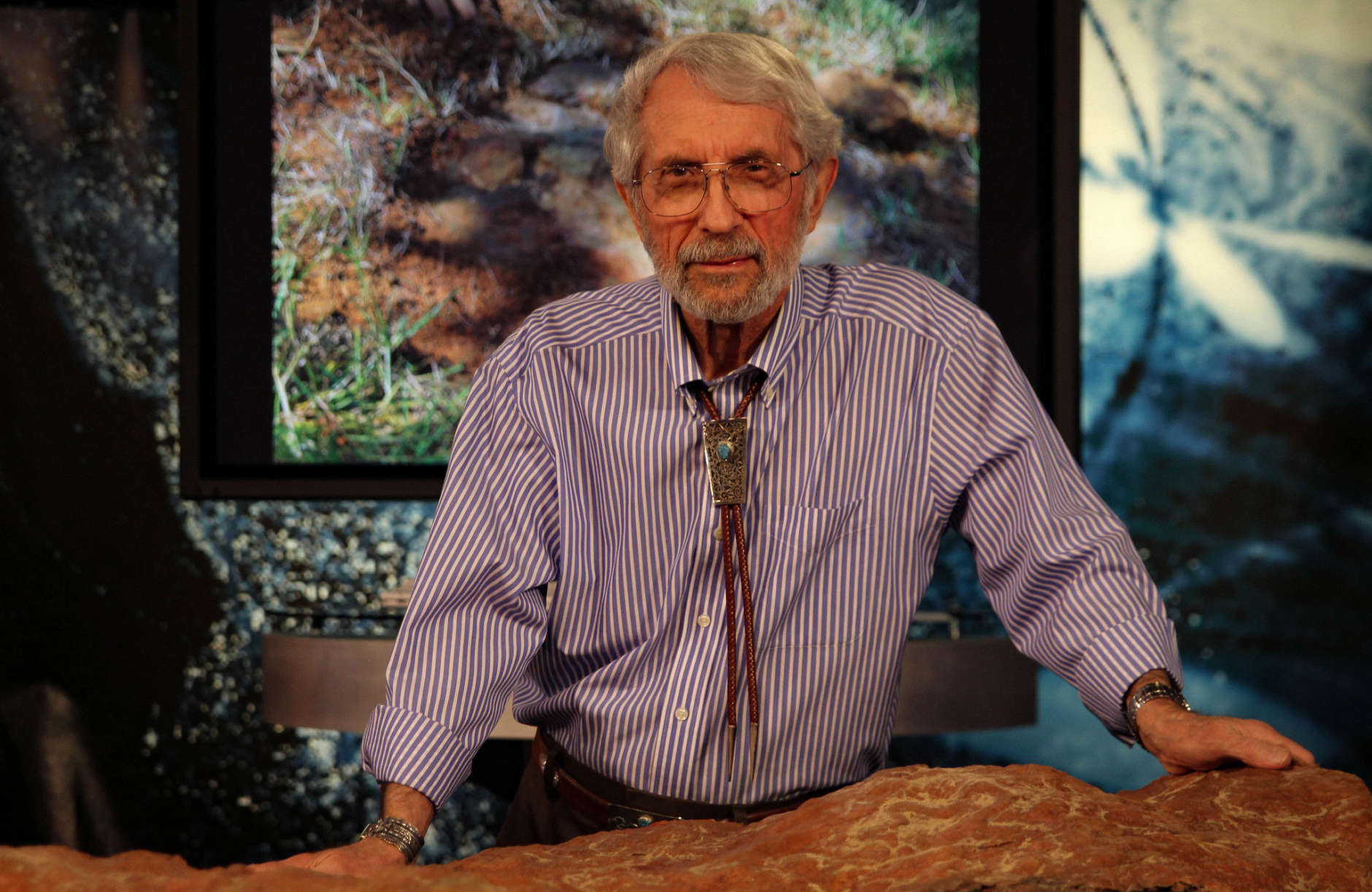

WASHINGTON — Ray Stanford was dropping his wife off at work in Maryland in 2012 when he saw an intriguing rock formation. In a paper released Wednesday, scientists are saying his find led to one of the most important discoveries ever in paleontology.

Stanford, a dinosaur track expert from the D.C. area, was bringing his wife to her job at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, in Greenbelt, when he found what turned out to be a single dinosaur track from the Cretaceous era.

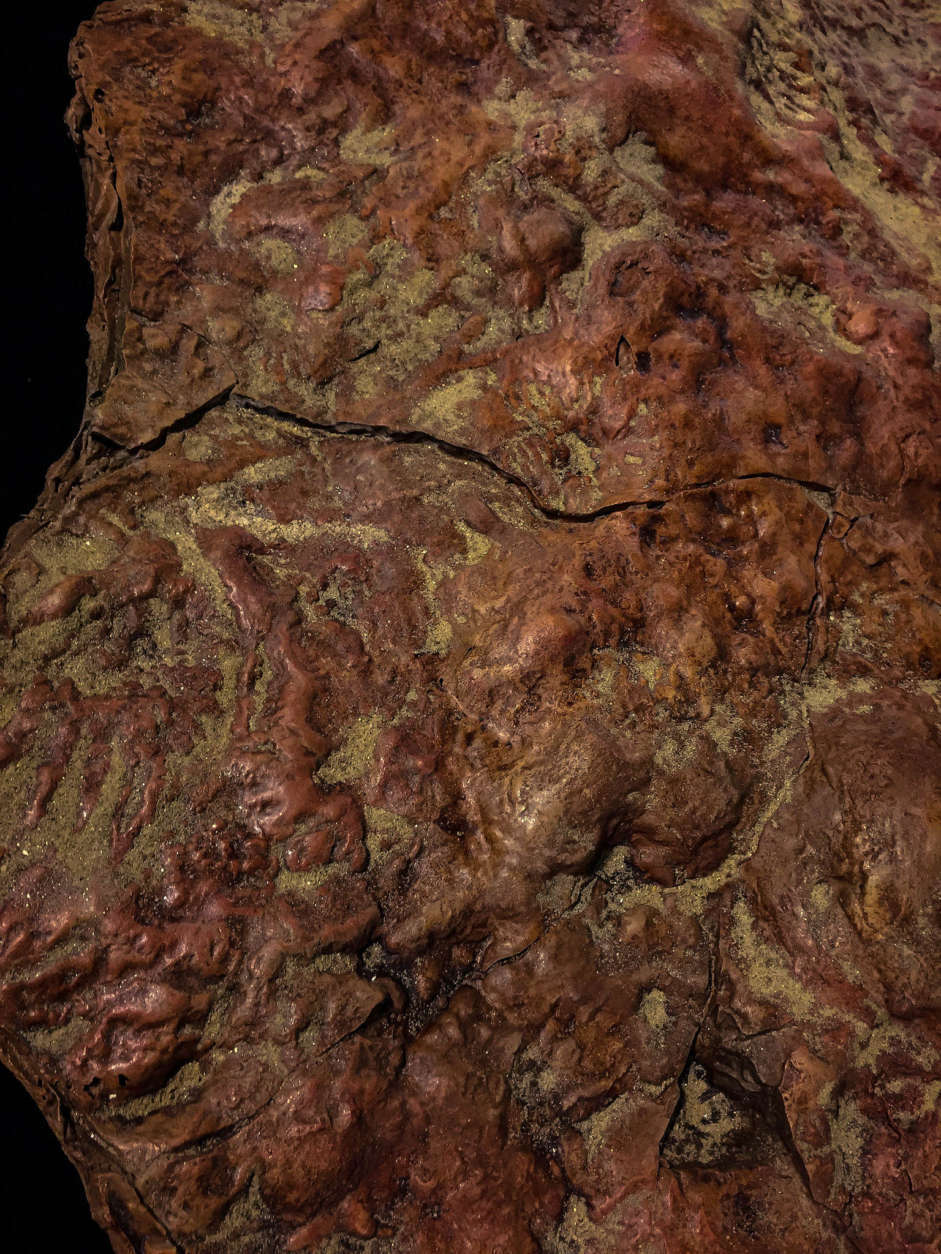

That led to an excavation that revealed exceptionally preserved body fossils and more than 70 dinosaur and mammal tracks from eight species — all displayed on a slab 8 feet by 3 feet.

“When I realized what was on this slab, it took me about three nights to get three hours of sleep,” Stanford told WTOP. “No one had ever seen this many classes of animals interacting with each other and in a small environment of only about two square meters of space.”

“The concentration of mammal tracks on this site is orders of magnitude higher than any other site in the world,” Martin Lockley, paleontologist with the University of Colorado Denver, a co-author of the new paper, said in a NASA news release.

The tracks depict Stanford’s initial discovery — the tank-sized, plant-eating, armor-plated nodosaur. But there are also the footprints of small flying reptiles commonly known as pterodactyls, foot prints of small squirrel- and badger-sized mammals and crow-sized predators related to velociraptors and Tyrannosaurus rex.

There are at least 26 mammal tracks.

Stanford said the way the tracks intertwine and are spaced suggest the flesh-eating dinosaurs were scoping out the area, looking for mammals to consume.

“Nowhere in the history of paleontology have we seen the actual mammals and the theropod interaction, where it seems one is waiting to eat the other,” Stanford said.

Other factors make the finding unique.

The great number of tracks on the slab is one of the highest track densities and diversities ever reported; it’s one of the largest collections of Mesozoic mammal footprints ever discovered, and the organic material in the former wetland setting created exceptionally preserved body fossil remains — there are no other similarly preserved fossils in the world.

The combination of the flood plain where the creatures left their tracks and the fine-grained red material in that plain is a unique environment.

“Fine grain is extremely important in getting good details in footprints and that’s what was existing here 110 million years ago,” Stanford said. “We don’t see this … anywhere else in the world.”