WASHINGTON — Like any mom, Yanique Campbell-Jennings worries about her son.

But after a string of highly publicized killings of young black men at the hands of police, the Germantown, Maryland, mother of three feels she has new reasons to worry.

“Eleven-year-olds are being shot by police …. He’s not too far from that,” she said of her 8-year-old son, Xavier.

Campbell-Jennings has already sat down her son to talk to him about racial discrimination, to explain how he, as a black boy, might be treated unfairly by police and what to do should he ever encounter law enforcement.

“We tell him to be respectful and follow the law,” the 38-year-old said.

Although clashes over monuments to the nation’s Confederate and slaveholding past have dominated headlines in recent weeks, police violence has become a modern flashpoint over race relations in the years since Michael Brown, an unarmed black teen, was killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014.

More deaths would follow. Walter Scott in South Carolina, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Freddie Gray in Baltimore and Philando Castile in St. Paul.

The spread of smartphone cameras has given Americans a ready tool to confront violence and document discrimination by police. And it’s changed the conversation: forcing parents to address the realities of race in 2017 America and forcing local police to rethink everything they do, including rolling out new training that emphasizes de-escalation and how to make traffic stops safer.

The talk: Confronting discrimination

The first time Campbell-Jennings and her husband, 53-year-old Colin Jennings, spoke with Xavier about race and police, another black teen had been killed.

They told Xavier to follow the officer’s directions, say “yes sir,” to be respectful and to tell the truth, she said.

But she worries that the message she relayed to her son was to be scared.

“It feels like we are telling him to put his head down,” she said.

She wants to equip her son with knowledge about what he’ll face in the years to come — in school, at the mall, even in the office — but there are few resources for parents, there is no guidebook. She and her husband had to draw from what she called their own moral compass.

“We can’t not address it … you can’t shelter him from it. The best thing is to talk to them as soon as possible,” Campbell-Jennings said.

Virginia Del. Jeion Ward has had similar conversations with her own family about what to do when stopped by the police.

“It’s one of those talks that I believe that all families have — I know black families have them,” said Ward.

And it was one of those talks — between her son and her grandson — that spurred Ward to introduce legislation aimed at taking away some of the fear, both for drivers and police officers.

“We have always known, always believed that the law wasn’t always equal. That’s an assumption that you grow up with. You don’t want to just keep passing it along irrationally to the next generation,” said Ward, who is black and grew up during the tumultuous Civil Rights era.

Because of her work, drivers education students in Virginia will now be taught what to expect when they are stopped by police and how to respond. Schools will begin teaching the new curriculum this fall.

The goal is to stop a simple traffic stop from escalating, Ward said.

Police deploy new tactics

In the nation’s capital, police are also talking, but the conversation is focused on how to be more respectful to the community they serve and how to defuse encounters before tensions rise.

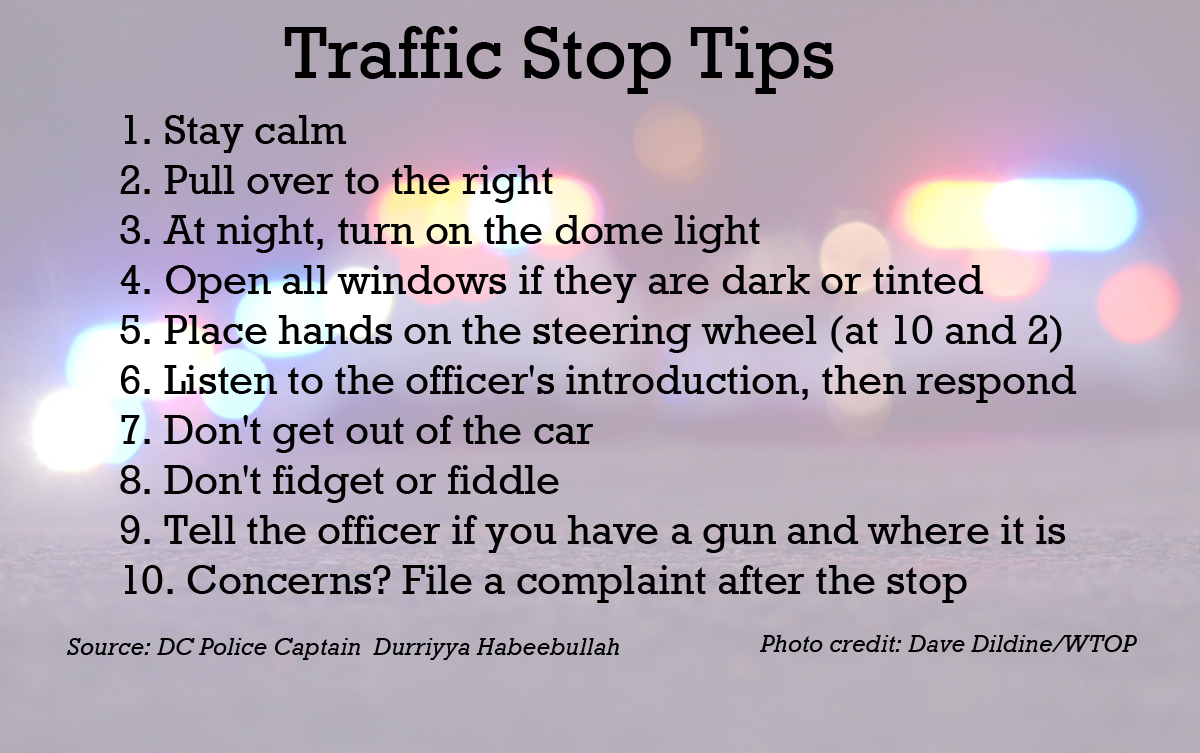

“It’s important that we do second guess things that we do as law enforcement officers because the world is watching. The people are watching. And we cannot operate in the manner that we operated in years ago. We have to be understanding to the people that we engage,” said Durriyyah Habeebullah, a captain at the Metropolitan Police Academy.

Starting last year, all D.C. police officers began receiving mandatory training to apply de-escalation techniques to all aspects of policing, including traffic stops, Habeebullah said.

“It’s in everything we do. Every portion of our training, we’re teaching de-escalation,” she said.

She points to how officers approach a car during a traffic stop as one example of how training has changed.

If an officer is uncomfortable standing too close to passing cars on the driver’s side, that’s when their anxiety can rise. So instead, officers are trained to approach on the passenger’s side, she said.

“We want people to stay in composure,” she said of officers. “Pulling people over and having traffic stops, we want it to be a nice thing, if that’s possible, but it can be.”

Police are also trying to explain themselves more so that the drivers know why they’ve been stopped, to have a conversation with the driver, she said.

“[Drivers] need to have a reason. They should understand the process and why they’ve been engaged by police,” Habeebullah said.

Several other area departments are applying the new approach to training, including Prince William County and the city of Baltimore, said Christy Lopez, a professor at Georgetown Law School.

Not all training is created equal. In some cases, training contributes to systemic misconduct among police agencies. As a former Department of Justice official, Lopez investigated police misconduct among departments in Ferguson, Chicago and New Orleans.

Some training can also amplify officers’ fears of traffic stops, Lopez said.

“Officers are told that traffic stops are dangerous, but they aren’t really given the tools to deal with that appropriately,” she said.

De-escalation training focuses on giving officers more time and space so that they can consider options other than deadly force, Lopez said.

Officers learn to detain, not chase; to wait for backup rather than engage; to take cover, not shoot, she said.

Bringing everyone home safely

Conversations about what to do when stopped by police, while practical and necessary for some, strike fear into the heart of Heather Gallagher, whose husband is a D.C. police officer.

She worries that merely discussing the topic publicly could incite violence toward police. She points to shootings in Dallas and Baton Rouge that killed eight police officers in 2016.

“I send my husband out every single day not knowing if someone is going to kill him just because he made a career choice that they don’t like. I have a 5-year-old. It scares the hell out of me,” Gallagher said.

A history of brutality at the hands of police has fueled that mistrust, said Habeebullah, the D.C. police captain.

She hopes that the new approach to training can help change that narrative in the District.

“You want people to be invested in the police department. And the only way you can have that is if people trust you and people respect you and you treat people the same way.”