WASHINGTON — Local high school students Daiana James and Kyle Fox Shreve are prepping for a major national competition that kicks off this week. But their training doesn’t involve carb loading, stretching and weight training; for them, it’s all about memorization and recitation.

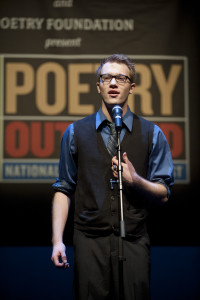

James and Shreve compete with poetry, and this week, they’re headed to the national Poetry Out Loud competition at George Washington University’s Lisner Auditorium, where they’ll attempt to beat out 51 other high school students from all 50 states, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico for a first-place prize of $20,000.

Both teens never predicted they’d eventually compete on stage with stanzas and sonnets. It just started with a routine English assignment: find a poem and recite it in front of the class.

“I reluctantly did it. I did the assignment and I did well, apparently,” says Shreve, a freshman student at Tuscarora High School in Frederick, Maryland.

So well, in fact, that he went on to win his school, county and state poetry recitation competitions. Now, he’s a fan of a subject he never considered.

“It’s a very cool thing, poetry. It’s very expressive,” he says. “It’s been a very surreal experience because I was not expecting to do anything like this going into my freshman year.”

James, a student at Benjamin Banneker Academic High School in Northwest D.C., participated a little more willingly. She describes herself as a bookworm, so when her teacher asked her to participate in the classroom contest, she didn’t think twice.

“It was never as issue of ‘I don’t want to do it but I have to do it.’ It was like, ‘Oh yea. I’m getting a grade for this, too? Awesome,’” she says. Similar to Shreve, James advanced to her schoolwide competition and then took first place among other high school students in the District.

What does a poetry competition entail?

Preparing for a poetry competition starts with memorization, the teens say. For the national Poetry Out Loud event, which is in its 10th year, participants are required to select three different poems to recite on stage.

They have their favorites, but both James and Shreve try to branch out, too.

“I hate to be cliché, but I love Shakespeare. If there was ever a time where I had to do something on the spot, it would probably be Shakespeare,” James says.

When Shreve picks a new poem for competitions (he prefers more contemporary poetry), he immediately grabs a notebook and writes the lines down as many times as it takes until all of the words are committed to memory.

“I rewrite it to the point that I can say it without even thinking about it,” he says. “When I’m up on the stage, I don’t want to worry about what I’m going to say next; I just want to worry about how I’m going to say it.”

The competition’s participants are judged on accuracy, difficulty and delivery, which James says is always the trickiest component.

“They say it’s not like a monologue, you shouldn’t have costumes or props or make any big gestures,” she says. Balancing emphasis and emotion is something both of the teens have to practice, but James says nailing the delivery is easier when she selects a poem that resonates with her.

“At the end of the day, if you love that poem, you love the words, you love the message, the rest of it sort of follows suit,” James says. “It’s all about analyzing it, and what connections can you make with these words.”

Over the past 10 years, Poetry Out Loud, which is a partnership between National Endowment for the Arts and Poetry Foundation, has reached about 3 million students in more than 9,000 schools.

Jane Chu, chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, says the program was started to help students refine skills in public speaking and to spark an interest in poetry. She says it also builds confidence — a quality Shreve noticed immediately.

“I’ve been told, growing up, that I’m very shy, and actually when you recite poetry … you get up there and you feel confident. It builds confidence,” he says.

Of course, the competition’s winner will also be able to build something else, such as a college fund — even if the teens would rather spend the $20,000 on something a little more exciting.

“Will my parents be listening to this?” Shreve jokes. “OK, yeah, [I’d spend the money] on college.”