Listen to Neal Augenstein reflect on his year with cancer – all this week on WTOP-FM.

You probably remember about this time last year I started coughing. I didn’t stop coughing until I was diagnosed and began treatment for stage 4 lung cancer.

By now, you likely know that after a couple months of coughing, I was surprised to learn in November 2022 that I had cancerous tumors and lymph nodes in both lungs, at age 63, with no history of smoking.

Fast forward, after five months of one-pill-a-day targeted therapy, and a robot-assisted lobectomy, my oncologist said I had no evidence of disease — or NED.

I’ll be the first to acknowledge I’ve had good doctors, good medicine, good insurance and good luck on my side — not to mention countless warm wishes and prayers from folks who know my work at WTOP.

My hope is sharing my journey may make the experience a little less scary for others diagnosed with the leading cause of cancer death in the U.S., according to the American Cancer Society.

So, one year in, I decided to interview three key members of my treatment team at Inova Schar Cancer Institute. I’ll introduce you to the doctor who first told me and my wife that I had cancer, the surgeon who removed the upper lobe of my left lung and the oncologist who has overseen the process of stopping the spread of my cancer, shrinking it, removing any remnants and minimizing the likelihood of recurrence.

And, just as importantly, he provides information and support, as I live life with stage 4 cancer.

Fear and diagnosis

This video is no longer available.

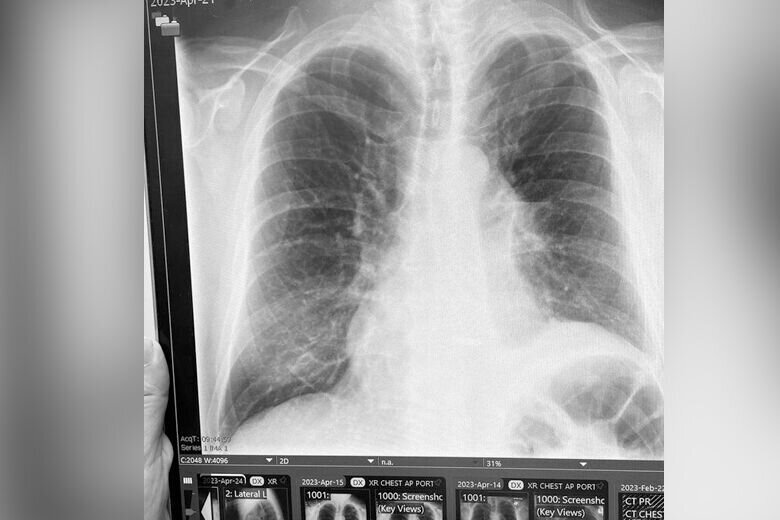

I first met interventional pulmonologist Bobby Mahajan, the medical director of interventional pulmonology for Inova Health System, in the minutes before he performed my bronchoscopy and biopsy at Inova Fairfax Hospital. The goal was to figure out why I had been coughing, and why chest X-rays and CT scans showed a mass in my left lung.

“There’s a ton of things it could be, but my job is to always think of the worst case scenarios,” said Mahajan. “When we saw your scans we said, ‘look, there’s something up.’ We worry about cancer because we know 20% of cancers that are lung origin are from nonsmokers.”

Young and confident, Mahajan patted my shoulder before the anesthesiologist started my Propofol, assuring, “We’ll take good care of you,” before I started the backward counting into deep sedation.

I didn’t know it at the time, but while I was asleep, and even before he took a biopsy, Mahajan was pretty sure I had cancer.

“I could see your lymph nodes and that mass under ultrasound,” he said. “There’s certain characteristics that make it more concerning — something that’s a really dense lesion on ultrasound, usually means there are cells that are really packed together, and that’s more indicative of cancer.”

Within a few hours, while I was resting comfortably in my hospital room, Mahajan broke the news to me and my wife. He expected the biopsy would show I had adenocarcinoma, a slow-growing form of non-small cell lung cancer.

Before I became weighed down with what I previously assumed would be life-changing news, Mahajan provided hope.

“When we met that night, I could give you good information, and my anticipation, based on your history, was ‘look, this is going to be turned into a chronic disease, we want to make this something that can make you disease-free,'” he said.

By the time he talked with my wife and I, Mahajan had already sent my biopsy for biomarker testing.

“We’re able to now look at biopsies, to test if someone has a certain mutation,” he said. If they do, that allows us to target your treatment.””

‘A difficult conversation — and an important one’

This video is no longer available.

Before I went to sleep that night, my oncologist, Amin Benyounes, visited me.

“When I walk into someone’s room, when they have just been newly-diagnosed with cancer, I realize it must be very challenging, and sometimes devastating news for someone to hear,” he said.

Soft-spoken and measured, Benyounes, a thoracic medical oncologist, who still usually calls me Mr. Augenstein, said in the next few days I would have a brain MRI and PET scan, to determine whether my cancer had spread beyond my left lung and a lymph node in the center of my chest. And, he was already arranging for my wife and I to meet with him, a radiologist and a surgeon, the following Monday.

When we met on that Monday, some of the test results were still pending. With a black Sharpie, he drew a chart of the possibilities that lay ahead.

Most important, biomarker testing showed my cancer had the epidermal growth factor receptor mutation — EGFR 19 Deletion — which has a targeted therapy available.

If my cancer was limited to one lung and the lymph node in the center of my chest, Benyounes said it would be considered Stage 3, and was curable, with radiation and chemotherapy. If it spread, it would be stage 4, treated with targeted therapy, “and the prognosis would be years.”

During our recent interview, I told Benyounes that was the first time someone had suggested my life might be cut short. I had done enough reporting to know that people often die with stage 4 lung cancer.

“Yes, Neal, it is a difficult conversation to have and an important one as well,” he said. “Sometimes, if you don’t call things by their names and tiptoe around concepts and notions, there can be a misunderstanding.”

If you Google stage 4 lung cancer — and I certainly had, before I was diagnosed — you’ll see the statistic that patients have a 1 in 4 chance of living another five years. I’ve never asked Benyounes how long he expects I’ll live.

“Those numbers and percentages are just a rough estimate. The person who is sitting in front of me is not a number. Each person’s journey is unique. Each person’s outcome is different than anybody else,” he said.

When my PET scan showed cancer in both lungs, that meant stage 4. I knew my treatment would be one pill of Osimertinib — with the brand name of Tagrisso — daily. The side effects of Tagrisso are generally quite tolerable, and far fewer than chemotherapy.

My cough was gone within weeks. Amazingly, after four months, Osimertinib had killed all but the tiniest remnants of cancer in both lungs, and surgery was back on the table.

Surgery, then home the next day

This video is no longer available.

When I first met surgeon Michael Weyant in November, surgery wasn’t an option.

“The day you walked in the door there was no way your body would survive the surgery necessary to extract all the tumor cells from you. If you had surgery on both lungs, in multiple lobes of your lungs, you would almost envision a lung transplant being needed to remove all the tumors, which really wasn’t feasible,” said Weyant, the director of thoracic surgery at Inova, during our recent interview.

By early April, “the drug you got remarkably reduced the overall number of tumor sites in your body and narrowed it down to one single area,” said Weyant, who said he could now do a lobectomy, with minimally-invasive robot-assisted surgery.

Advances in lung surgeries have been monumental in recent decades, said Weyant. “In the 1960s and ’70s the only option of entry into the chest was a very large incision that curved around your shoulder blade. The large incisions and the spreading of the ribs induced a fair amount of pain for patients after surgery.”

These days, Weyant sits in a console, operating the robot. Four tiny robot arms — a left hand, a right hand, a retraction device and a camera, went through tiny incisions on my side and back.

After spending the night sleeping sitting up, with a chest tube inserted, Weyant visited me early the next day, verified my lung wasn’t leaking, and sent me home.

“I’d be more than happy to be put out of business because a medicine was developed that would obviate the need for surgery,” Weyant said. “It wouldn’t bother me one bit — that would be an incredible advance in science and medicine.”

‘We work our way out of that hole’

Even though I’m now cancer-free, since I was diagnosed with stage 4, I probably will never hear the phrase “you’re cured.”

“Unfortunately, a tumor at any stage has the ability to resurrect itself and return,” said Weyant. “That’s why we think that surveillance after treatment of any tumor is really important, and that’s not unique to lung cancer, per se.”

With CT scans every three months, and less-frequent brain MRIs and PET scans, I still take my Tagrisso, to try to stem cancer’s recurrence.

Benyounes said until recently, “the stage that the person is diagnosed with is, so to speak, the stage that person stays in.”

“This has clearly been challenged,” said Benyounes. “We are thankful and grateful that we have patients that beat the preconceived notion that someone with stage 4 cannot be cured from their disease.”

With recent improvements in treatments, “All of us in the lung cancer community have patients who were diagnosed with stage 4, who are no longer even on any cancer treatment, because there was no evidence of disease for a long time.”

Benyounes said being forthcoming with patients is important for building trust.

“This is going to be a long-term relationship, and setting realistic expectations goes a long way,” he said. “I think most people appreciate a healthy balance of optimism and realism.”

And while he doesn’t want to provide false hope, Benyounes says equipping newly-diagnosed patients with accurate information is empowering: “This gives us back a sense of control, which initially we completely lack. Gradually, we work our way out of that hole we initially found ourselves in, after just being given devastating, life-altering news.”

New developments in biopharmaceuticals and operating room technology are in the works.

“We live in a very dynamic time, when it comes to cancer treatment. We have so many world-class institutions within driving distance that offer the most promising cutting-edge clinical trials,” citing facilities in Maryland, D.C., and Northern Virginia.

Benyounes says these days, when he walks into the room of newly-diagnosed lung cancer patient, “more often than not, I can promise there are many good days and years ahead of them.”

After one year with lung cancer, I feel healthy, hopeful and empowered.

“I think time also plays a role. As one continues one’s life, things, for the most part, don’t turn out as bad as they thought they would,” said Benyounes.

“They find themselves in a better spot, hopefully well taken care of, and that they’re able to continue their life, despite cancer.”

I intend to follow doctor’s orders.

This video is no longer available.