Sickle cell disease prompts bouts of excruciating pain that is tough on kids, and a Maryland boy’s hope for a cure may depend on more people joining a blood stem cell registry.

“Kameron’s pain usually hits his arms, his legs or his back,” Antoinette Burrows, of Upper Marlboro, said of her grandson, 5-year-old Kameron. “As he is getting older, he’s doing a great job in managing that pain.”

September is Sickle Cell Awareness Month. It’s a deadly disease, and Burrows said Kameron was in and out of the hospital frequently as a baby.

“There were times we didn’t think he would make it to be 5 years old, but he’s here,” she said.

But he spends some days wracked with pain.

“And when that happens, he’s usually still; he has to be still; he lays in bed,” Burrows said.

Burrows describes Kameron as an amazing, optimistic child who loves Transformers action figures, enjoys playing soccer and going to his Ninja Class.

“He thinks he’s a super hero,” she said.

“He lives as normal a life as possible,” Burrows said. “We don’t really inhibit him from anything, unless when he’s sick. But we try to get him involved; we don’t want him to miss out on life.”

As part of Sickle Cell Awareness Month, the American Red Cross is emphasizing the unique role Black blood donors play in the medical treatment of those living with sickle cell disease.

“Because most people who have sickle cell disease are of African descent, Black blood donors may be the best match for sickle cell patients in need,” Regina Boothe Bratton, American Red Cross spokeswoman, said. “A patient in need is more likely to find a compatible blood match from a donor of the same race or a similar ethnicity.”

The Burrows family also is trying to encourage more minority donations.

“We’re working with the Ruby Ball Foundation to get more African Americans to do blood donations,” Burrows said. “Children with sickle cell are in great need of transfusions at times. And sometimes, you don’t have the blood to give to them. So get to your nearest hospital. Get to your nearest blood drive and give, give, give.”

The only hope for a cure for Kameron would be to find a matching blood stem cell donor.

“There’s a match out there somewhere; we just need to find it. But we can only find it, if you get tested,” Burrows said.

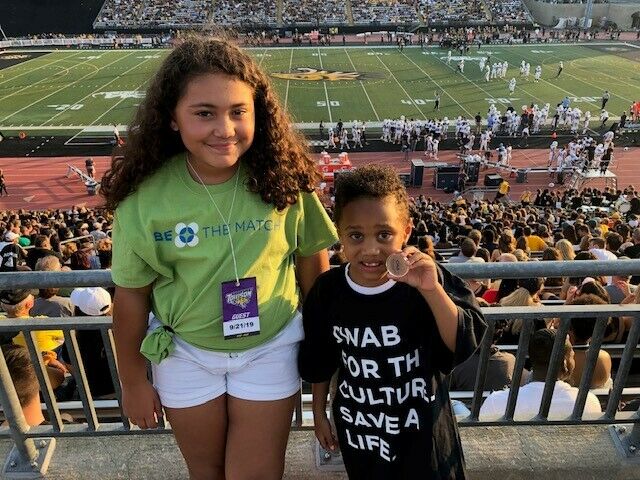

Other D.C.-area children whose lives could potentially be changed by someone choosing to join the Be The Match registry include teenager Ben Lesser, of Bethesda, and 4-year-old Ailani Myers, of Severna Park, Maryland.

“There’s a quick little survey that you take to see if you’re even eligible to even go to the next step. It’s less than a minute,” Burrows said.

Learn more about the Be The Match registry.