WASHINGTON — The measles outbreak concerns many in the medical community, including the man who co-created the vaccine more than 50 years ago.

Dr. Samuel Katz came of age as a pediatrician and virologist back in the 1950’s — a time when measles and other childhood diseases like chicken pox and mumps were prevalent.

“Before the vaccine, it was estimated that we had three or four million measles cases a year, and about 50,000 hospitalizations and about 500 deaths,” Katz recalls.

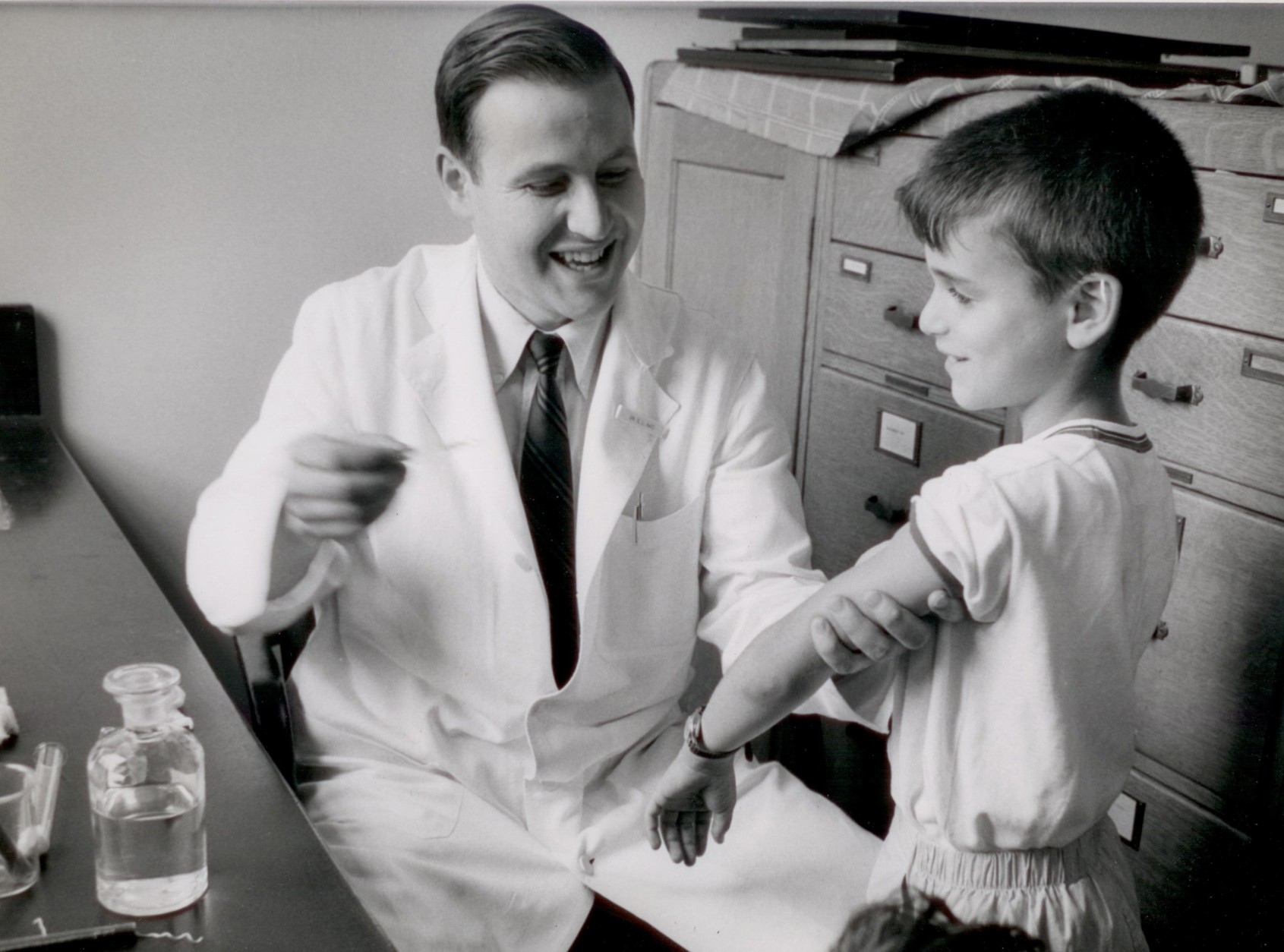

He worked in the lab for 12 years, conducting research using cell cultures and eventually testing a vaccine in monkeys. When it was proven safe and effective in primates, Katz injected himself and his four children, much to the dismay of his wife.

His son David was a small boy at the time and doesn’t remember the shot. Now a doctor, lawyer and health care expert in Potomac, he puts his “test baby” status in perspective.

“It doesn’t surprise me that my father would have enough confidence in his work to use his children as part of the trial,” David Katz says.

As David points out, his father wanted to protect his kids from what could be a devastating illness. He describes his father as very humble; the kids often learned about his accomplishments in a rather roundabout way.

“I do remember at a very early age, watching our tiny little black and white television because my father was going off to help in Africa — in Nigeria — for several months,” he recalls.

Sam Katz laughs at the recollection, but turns serious when he addresses the dire situation he found in the developing world: a measles crisis far beyond what he had seen in the United States.

It was 1963, and the measles vaccine had just been approved for use in the U.S. Katz took it to Nigeria at the request of a British pediatrician who ran a local clinic, where ten to 15 percent of the children who came down with measles died from the disease.

“When we went to Nigeria, the thing I learned was mothers would say ‘you don’t count your children until measles has passed’ because they knew how many children died,” he says.

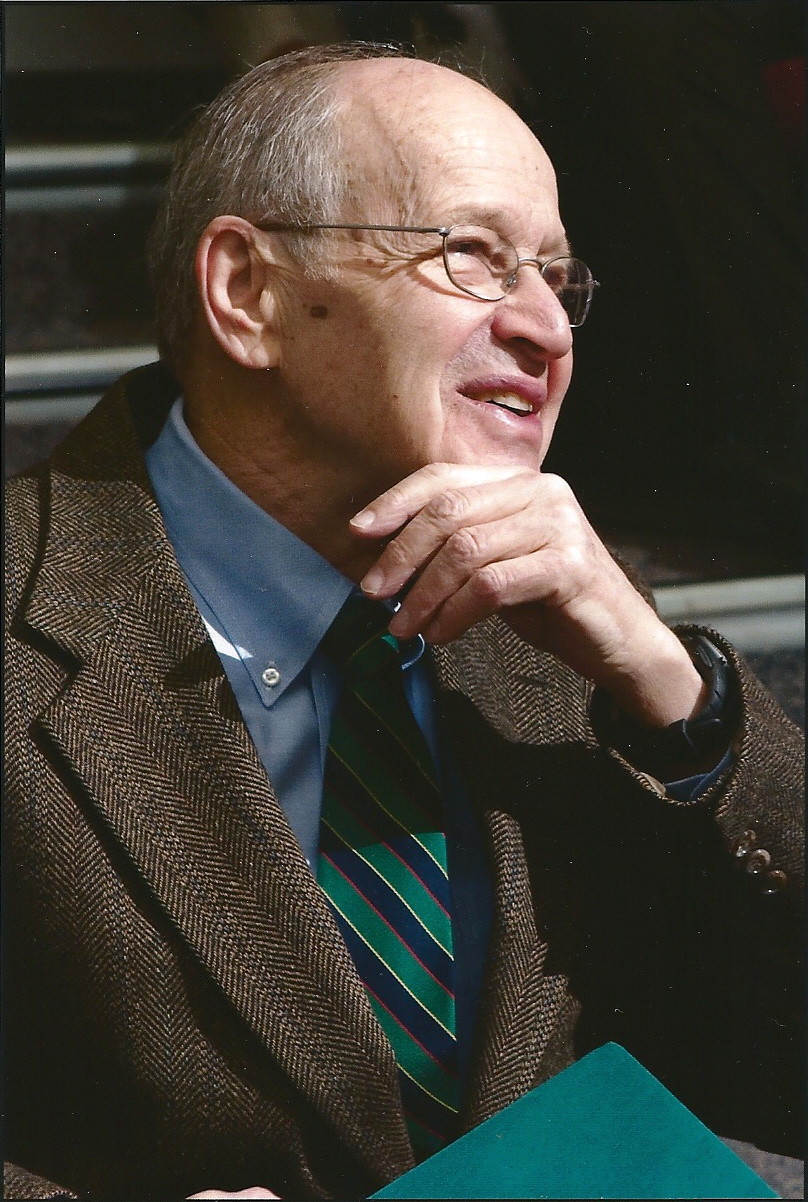

The trip turned him into a health advocate for all children — both here and abroad. At age 87, he is still speaking out and advising global vaccination efforts from his post as chairman emeritus of pediatrics at the Duke University School of Medicine.

His son says he must be frustrated about the current anti-vaccine movement. But Sam Katz addresses the controversy in calm tones and carefully chosen words, saying he prefers the term “vaccine hesitancy.”

He says parents reluctant to vaccinate their childen “are mostly people who are unfamiliar with the disease.” Sam Katz urges them to study history and learn about the way previous generations had to deal with a disease that wasn’t as innocent as some currently believe.

Katz wants to remind them that measles can be a killer — with 140,000 deaths each year in Africa. He says his message is the vaccine is safe and measles can be dangerous.

But Sam Katz adds the most effective voice on behalf of vaccination is not his. He says it is the collective voices of the mothers in Nigeria who told him they would not count their children until measles had passed.