This story is part 1 of a 3-part WTOP special report on how the new Advanced Placement African American Studies course is being taught at high schools in the D.C. area. Part 2 will be available Thursday, May 16.

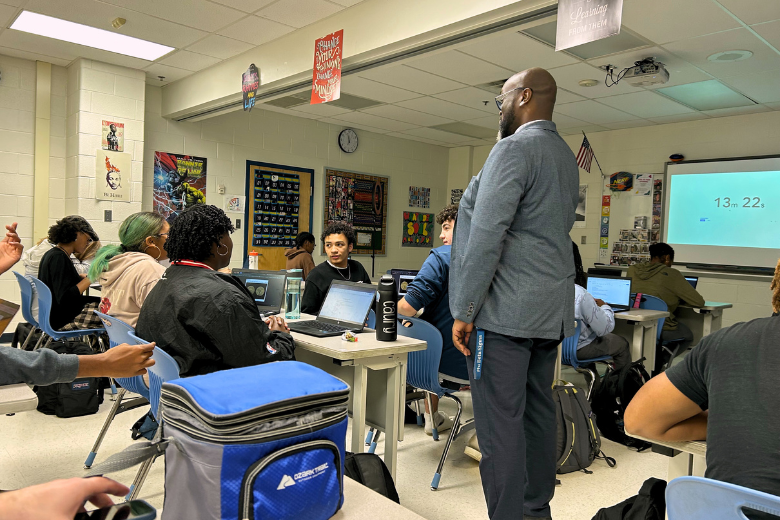

Standing in the front of his Lorton, Virginia, classroom in October, Sean Miller told his students that food would be a topic of conversation during the class period.

He also said they would talk about the types of goods that emerged in ancient East and West Africa. Part of that would involve how the influence of gold shaped the development of certain African empires.

But first, Miller advised the class to pay attention to the video he was about to play. As part of a conversation about the cultural implications of food, he asked the class the types of food they’d expect to see at a Black family reunion.

Mac and cheese and cobbler were among the first responses.

As they watched the video, Miller recommended the students consider how food impacts culture, and how it plays a role in what “Black joy” is.

This video is no longer available.

Those types of conversations are common in Miller’s fifth period class, AP African American Studies. On some days, he lectures and discusses readings. On other days, he’s leading conversations about how culture has evolved, or the influence African American history has on topics such as music.

Of the nearly 200 public schools in Fairfax County, South County High School is one of the few schools piloting the new course. For months following the introduction of the course’s framework, some politicians across the country scrutinized it, arguing it was divisive or questioning how it could make non-Black students feel.

In Virginia, Gov. Glenn Youngkin ordered a review of the class to see if it violated an executive order banning schools from teaching divisive concepts. The state’s education department ultimately approved the class months later.

A spokesman for Youngkin did not respond to a recent request for comment on the course.

The class, educators in the D.C. region said, is becoming increasingly popular with all students. It’s emerging as a viable first AP course option to get students used to the rigor of the college level classes. It also, Miller said, goes beyond historical concepts taught in traditional history classes.

“What people will find is that the information is designed to give students a narrative that they often don’t hear,” Miller said. “It’s not meant to demonize anybody or demonize particular periods of time. But it’s just giving a full story.”

The framework, according to a class syllabus obtained by WTOP, spans four units: “Origins of the Black Diaspora,” “Freedom, Enslavement and Resistance,” “The Practice of Freedom” and “Movements and Debates.”

The textbook, “From Slavery to Freedom,” spans those topics and much more, such as what happened during an “era of self-help” and how challenges that African Americans have faced evolved over time.

Miller, who previously offered an African American studies course at South County, said when he was a student, he noticed the Civil Rights Movement and slavery were main topics, and others weren’t included.

“This, to me, is a cultural experience,” Miller said. “I always want my class to be something they’re never going to forget.”

The College Board altered the framework for the class late last year, removing concepts such as critical race theory. But Miller is aiming to bring other ideas, such as the Harlem Renaissance, to life in his classroom.

Senior Eden Fikru said she took the class to “get a different perspective that I hadn’t already gotten from the basic civil rights and slavery education. Being able to learn more about positive things that have happened in Black history.”

Other history courses, senior Leyat Samson said, don’t include much African or Black history.

“It’s just too often where we’re sitting in history classes, just being told Black history is slavery and Reconstruction and I feel like there isn’t anything on the positives and how people cope with that and how they resist it,” Samson said.

Through projects and lived experiences, Miller is hoping to fill that void for his students.

In December, he had the class gather outside to review a mural that his former students had painted. They learned about murals that relate to African American history in Phoenix, Arizona, and then were tasked with sketching a mural that they thought was connected to a nation or culture.

After winter break in February, he tasked the students with planning and executing a Black family reunion. They researched and made posters, and described how the items they each brought in were connected to a broader theme.

“Ultimately, when this class is over, that’s what I want students to do, take this concept, the concepts that were illustrated in this class, and realize that they can truly make history themselves,” Miller said.

Last month, Miller told his students to create a 10-minute podcast that makes connections between history and the modern world.

Some students chose to talk about slave rebellions and Black nationalism, “things in Black history that don’t get talked about,” Fikru said.

Another group picked the connection between music and history.

“Country music, and jazz and the blues, Black people were the roots of that,” one student in the group, Octavian, said.

Ahead of Tuesday’s AP exam, many of Miller’s 26 students said the class provided valuable insight into African American history and culture. And even after the exam, Miller said students will take trips to museums such as the National Museum of African American History and Culture to learn more.

“This isn’t a class that’s made to attack anyone,” Samson said. “It’s just to further us as students, it’s to further our perspective. And I think that isn’t really highlighted in our current history classes right now.”

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2024 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.