This is Part 1 of a three-part series on WTOP.com about DNA evidence, its evolution and how it’s being used in the D.C. area and beyond.

READ PART 2: How police use DNA evidence to work backward, and then forward

In 1993, Kirk Bloodsworth, a Maryland waterman, became the first American on death row to be exonerated by DNA evidence, after spending 19 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit.

Since then, numerous other convicted killers have been declared innocent by DNA evidence that proved someone else was responsible. But recently, advances in DNA science have also been used to bring about convictions as well as exonerations.

Those advances, combined with our own interest in finding out about our ancestry and heritage, have had a groundbreaking impact on police work. Just the tiniest amount of DNA material, and a few weeks’ time, can get detectives answers that have eluded them for years, even decades. The most famous example came last year with the arrest of a serial killer and rapist known as “The Golden State Killer.”

The closure of that decades-old case reverberated through the technology sector — it also led one local company to completely change its business model in a matter of weeks.

For the police, it’s revolutionary. For victims’ families, it’s invaluable. But it also raises concerns from privacy advocates and others who say the technology, and how it’s used, is an intrusion into the lives of people, and could be unconstitutional.

This week, WTOP is looking at how DNA is closing cases but also raising questions about the steps law enforcement is taking.

An overnight shift

Police departments around the country, including many in the D.C. area, are partnering up with private companies who can look at DNA samples in ways the police don’t have the resources to do. The end result leads to breaks in cases that had been stone-cold.

Parabon Nanolabs, based in Reston, Virginia, is one of those companies. They’ve been helping police crack cases in the area and nationwide — including the 1972 murder of an 11-year-old in California, which was solved earlier this month.

Parabon is a 20-year-old company that began as a software firm. About 10 years ago, Parabon “began realizing there was genetic content in DNA that wasn’t being exploited by the forensics community,” said CEO and co-founder Steve Armentrout.

In simple terms, the way scientists study DNA is similar to how a computer programmer might look at code. It took someone to create row after row of characters to produce this website, for instance.

“In that sense, code is responsible for output, and genetic code is responsible for the human being that possesses that DNA,” Armentrout explained.

Dr. Ellen Greytak, Parabon’s director of bioinformatics, said, “Ever since the completion of the human genome (in 2003) there’s been a lot of research … trying to understand what parts of the genome code for what kinds of traits.”

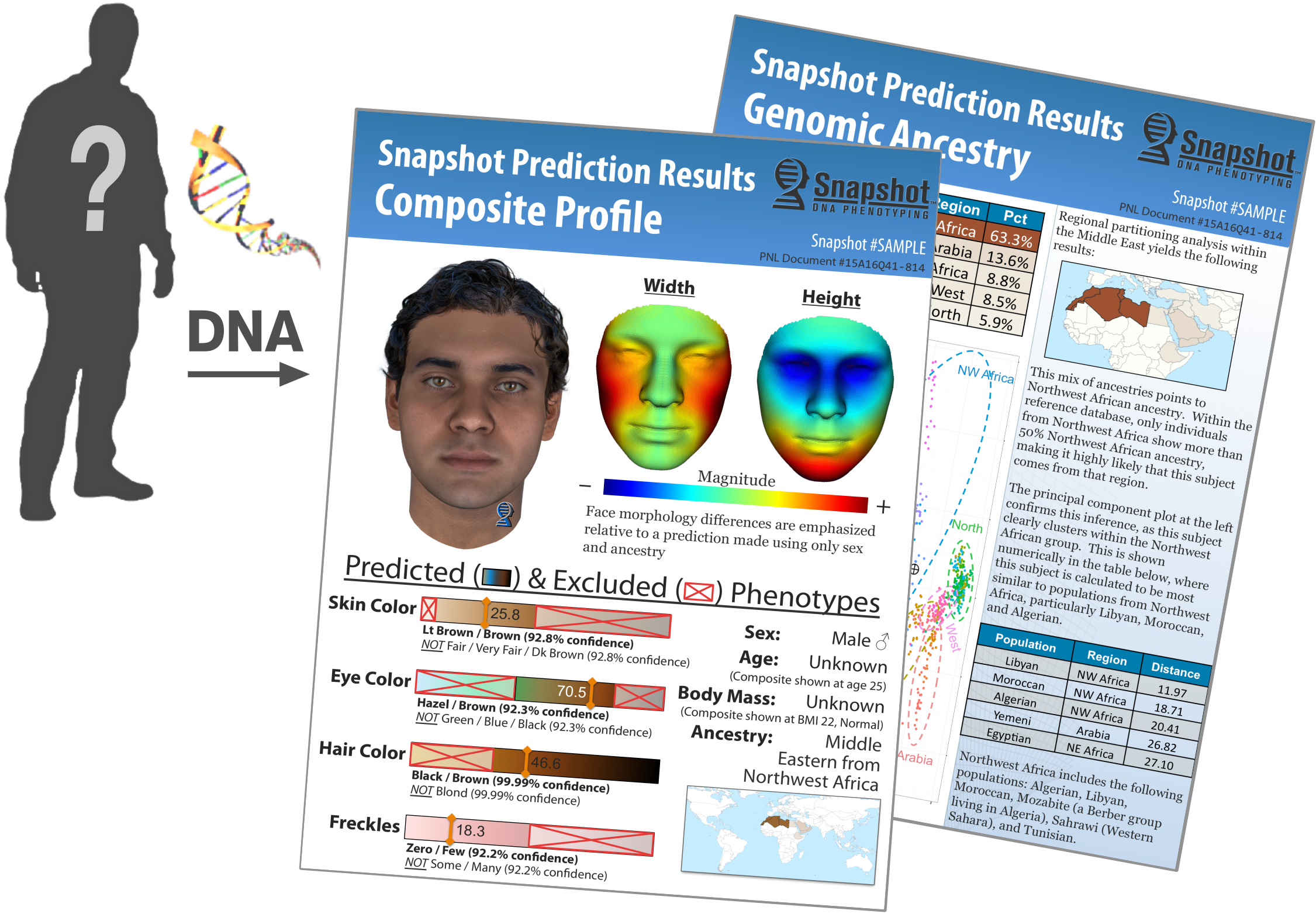

Most of the research focused on medical applications — trying to figure out, for instance, whether someone was more likely to develop certain types of cancers or other diseases. But scientists have also been able to use DNA to begin figuring out why you might look like you do — everything from the shape of your face, or just your nose, to your hair and eye color.

“When we talk about ‘Oh, you have your mother’s eyes,’ that’s because you have your mother’s DNA. It’s been passed down,” Greytak explained. “So we can find the parts of the DNA that actually code for the differences between people who have blue eyes versus green versus hazel versus brown.” Then they can build “a predictive model,” working in the other direction and using the DNA information to figure out what characteristics the person has.

“We say we need one nanogram of DNA,” Greytak said. That’s about one one-billionth of a penny, and it can come from blood, sweat, saliva, other bodily fluids or skin.

“When you have an unknown DNA sample at a crime scene where the detective has no description of that person, there’s no witness,” Greytak said, ” … we come along and analyze that DNA and say, ‘Oh, that pattern; we’ve seen that before, but we’ve only seen it in blue-eyed people.’ That’s oversimplified, but that’s the idea and then we can tell the investigator, ‘You’re most likely looking for a blue-eyed person; they might have green eyes but they almost certainly don’t have brown eyes.’”

That’s called phenotyping, and it’s how Parabon began working with the military and later with the police.

Parabon started working with the Department of Defense in support of missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, using phenotyping to help identify those responsible for leaving roadside bombs. The end result would at least give the military an idea of what their suspect might look like, based on how the DNA taken compared to other traits found in people.

Parabon also helped the military identify the remains of those lost in past wars — typically, soldiers killed many decades ago who didn’t have a known next of kin.

The predictive models were useful for the military, but even more intriguing to police departments. Parabon could come up with composite pictures of what suspects looked like — and unidentified crime victims too.

She added, “Then you add in hair color and ancestry and face shape, and you get to a smaller and smaller group of people you want to start investigating.”

Cracking a code

The arrest of a serial killer last year changed everything for Parabon.

Police in California announced the arrest of a retired police officer named Joseph DeAngelo, who was known as the Golden State Killer. The case was cracked by the latest advance in DNA evidence, called genetic genealogy.

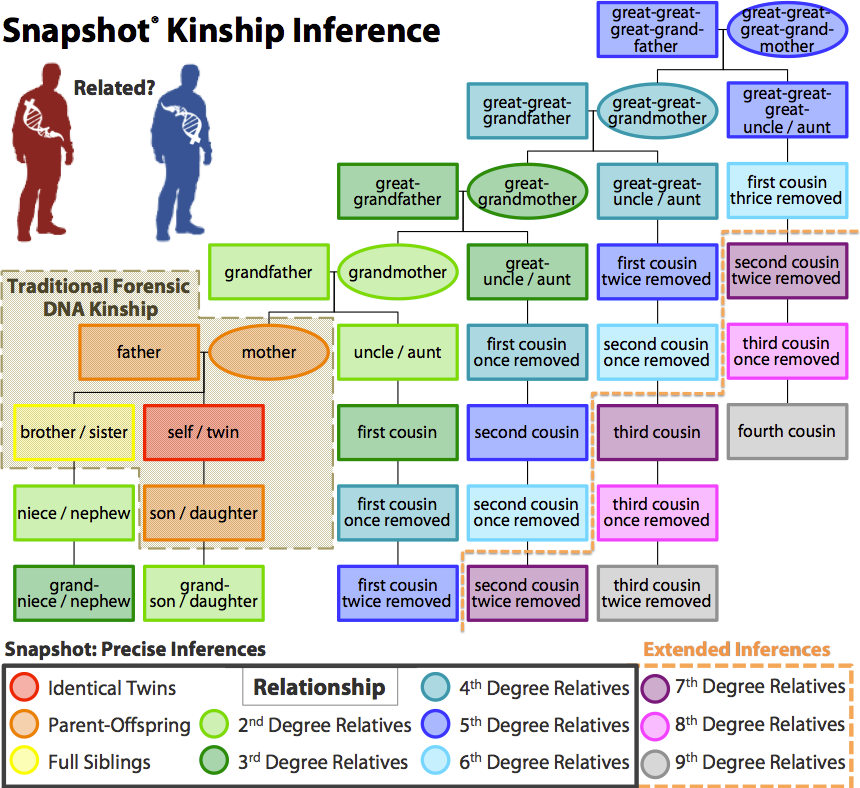

While Parabon didn’t work on that case, its method is similar: its researchers come up with a report that shows how closely the DNA obtained by police is matched with the names of people whose DNA profiles are already in public databases — typically, they’re people tracing their lineage.

Included in the report are names of relatives, sometimes distant relatives, of the suspect police have become stumped trying to find, and roughly how distantly related that person may be.

By that time, Parabon was already working with a renowned genetic genealogist named CeCe Moore. “Within two weeks’ time we had revamped the business model here, hired CeCe, and began using genetic genealogy as really our primary first offering,” Armentrout said.

Greytak said the level of specifics Parabon can determine now can truly help in a case.

“I joked, ‘Do you really care if he has blue eyes if we can tell you his name and address?’,” Dr. Greytak said.

“This is the up-and-coming thing in cold case investigations,” said Sgt. Christopher Homrock, who leads the Montgomery County Police Department’s cold case unit. And he should know: In recent years, his department and others in Maryland have used the technology to identify suspects and victims in cases going back decades.

Listen to John Domen’s series

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

READ PART 2: How police use DNA evidence to work backward, then forward

Coming Friday in Part 3: Is genetic genealogy constitutional? Is it legal in Maryland and D.C.?