Imagine being the greatest musician alive, until a prodigy steals your thunder.

That’s the theme of Peter Shaffer’s “Amadeus,” which won the Tony for Best Play in 1981, and the Oscar for Best Picture in 1985 for Milos Forman’s adaptation.

Now, it’s Folger Theatre’s turn to stage “Amadeus,” from Nov. 5 through Dec. 22.

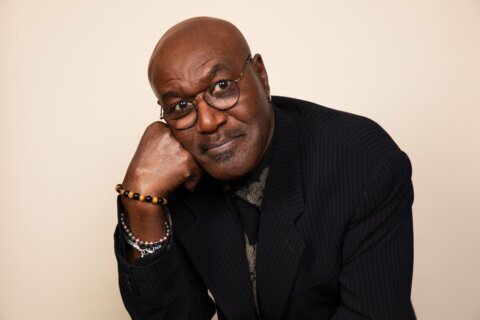

The play opens in Vienna, Austria during 1823, with rumors swirling that aging Italian composer Antonio Salieri (Ian Merrill Peakes) murdered Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Samuel Adams) three decades prior.

Salieri directly turns to the audience and confesses, flashing back to 1781 when young Salieri first encounters Mozart and becomes jealous of his God-given musical genius.

“We must say that this is completely fictionalized by Peter Shaffer,” Peakes told WTOP. “Historically, we know they knew each other and were friendly. There’s no evidence of this play being true, except that they were both composers at the same time and Mozart did die young.”

“There were little weird rumors that circulated in a town like Vienna, which was super gossipy and prone to scandals and conspiracy theories,” Adams said.

Whether or not Mozart was actually poisoned is irrelevant to the story, which explores a symbolic poisoning occurring between the two rivals.

“He does, but it’s emotional,” Peakes said. “Mentally he poisons him. He sort of gaslights him throughout, saying he’s going to do things that he doesn’t, and saying he’s not going to do things that he does. His point is much bigger; it’s about artistic genius and jealousy and how we deal with these things. He just uses these two as a vehicle for that story, which is pretty damn clever.”

Also driving Salieri is his devout faith, blaming God for his inferiority.

“If you have infinite belief in a higher power, then that higher power starts f-ing with you, you’re going to start doing some strange things,” Peakes said. “He was aware of the actual genius of Mozart and that he would never be as good as him, so that destroyed his life and made him a dark soul. … You think of him as a bit of a villain, but I’m more interested in playing him as not a villain [with] legitimacy to his actions. Now, he goes farther than you or I would, but his soul is crushed.”

Ironically, Mozart became much more acclaimed after his death.

“Mozart was very popular throughout his lifetime but wasn’t nearly as popular as he probably should have been,” Adams said. “Dying at 35, [just think of] the amount of material we might have had after that period. He wrote over 600 works by the time that he died. To imagine what kind of compositions he would have had when he was an old man would have been amazing.”

“To go back and listen to his stuff, you go, ‘That was ahead of his time,'” Peakes said. “It makes me think of James Dean and what his body of work might have turned into. You see what he was doing in ‘Giant’ you and think, ‘This is going to be one of the greatest actors of all time.’ People didn’t know what to do with James Dean because he jumped up two generations of acting style. Mozart was the same thing. People knew this was a star … touring Europe with his dad and doing tricks with his piano, but it’s hard to take a child prodigy seriously.”

Today, audiences will recognize the compositions as classical masterpieces.

“The director, Richard Clifford, describes the music as an additional character,” Adams said. “It’s such a huge presence in the play and in the story. Obviously, when you’re dealing with Mozart, music is going to be a pretty important factor, so we’ve been folding the music in. It’s written out in the play what music is included and where it goes, but the more we’re in the space with sound and tech, we find that having that music lifts everything up and brings it to a new level.”

“You forget how many really good songs Mozart wrote,” Peakes said. “You’re like, ‘Oh, that’s him, too!’ There’s also monologues inside the music. Normally, I hate background music because it’s telling the audience what to feel, but in this, it’s so helpful because it helps me to feel what Salieri might have understood, which was his demise. He was looking at his own death.”

It’s all brought to life visually on stage by scenic designer Tony Cisek.

“The set has one big shape to it,” Adams said. “Shooting out of the center of the stage are these big things that represent the inside of pianos, these big, long piano strings stretching across the stage. It gives you a sense that you have this golden musical iconic look, but it’s also like prison bars, so it’s kind of confining.”

“They also look like God rays from the sun, while being trapped behind bars, because it all takes place in Salieri’s mind,” Peakes said. “Every single audience member is going to have a different response. That’s what’s so great about the set is you create these images but everybody sees something different, but I think they all work. You’re gonna see bars, musical notes, God rays, whatever, but to just know that’s behind me and it’s my mind, it’s very, very helpful.”

The actors also relish the period costumes and wigs by Mariah Anzaldo Hale.

“Mariah Hale is the greatest,” Peakes said. “She’s really, really good and she’s collaborative. I wish all costume designers were just like that. … She hasn’t done this period before and you would never know it because she’s knocking it out of the park. Everybody looks fantastic. Literally in rehearsal people will walk on stage and there are audible gasps.”

Piercing through the costumes and music is Mozart’s signature laugh.

“You really need to come hear his laugh,” Peakes said. “It haunts my dreams.”

He is, of course, referring to Tom Hulce’s wild laugh that caused F. Murray Abraham to cringe in the film. But the cast isn’t merely doing impressions.

“I haven’t gone back to watch the film,” Peakes said. “I tend to not go back and look at something so it doesn’t feed me. I’m horrible at impersonations so there’s no point. I will watch it afterwards, but F. Murray Abraham and I are very different actors. We actually did a reading together once. … I don’t want anyone else tainting what I’m going to do or throwing ideas in that aren’t mine.”

“The way we’ve been going with it is to just do what is authentically our version,” Adams said. “Whether or not that’s similar or different from the film, I’m personally not trying to think too much like that. … The way that this play is written, it doesn’t have a whole lot of room for interpretation. … This play wants to be done exactly like this play wants to be done.”

Find more details on the theater website. Hear our full conversation below: