In 2016, Arena Stage presented Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play “Disgraced,” which to my eyes remains one of the most powerfully relevant productions that Arena has ever staged.

This week is your last chance to see his latest work, “Junk,” a 2018 Tony nominee for Best Play.

“Come for the witty repartee, stay for the $1,000 suits,” lead actor Thomas Keegan told WTOP.

Set in the cut-throat financial world of junk bonds in the mid-1980s, the story follows financier Robert Merkin, who plans a hostile takeover of a family-owned manufacturing company.

“My character is based on a real-life man named Michael Milken,” Keegan said. “Essentially their strategy was to raise hundreds of millions of dollars by selling sub-prime stocks, known as junk bonds, and using that money as leverage to take out a loan against a company in order to take it over, known as a ‘hostile takeover.’

“The play sorts through this in real-time. You get the financial side, some politics, family drama, definitely human stakes at play.”

That human drama includes Merkin’s own marriage and the family business in his crosshairs.

“In the play, my wife (Shanara Gabrielle) plays a very important role,” Keegan said. “She has an M.B.A. herself and has had a career on Wall Street, we have a newborn son, and the company I’m trying to take over is run by a man who’s running his father’s company, whose grandfather started the company. It’s this idea of legacy, succession and what we pass on for posterity.”

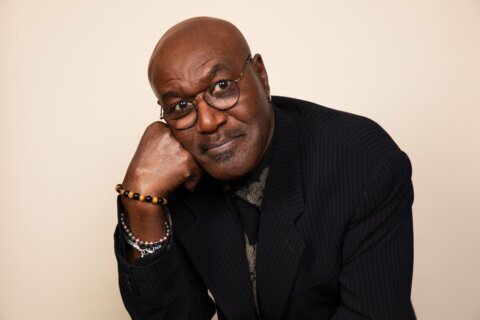

Along the way, Merkin bonds with colleagues, particularly legal aide Raúl Rivera (Perry Young).

“There is this idea of ‘us versus them,’ them being the old guard and the new guard being this young, upstart group of people trying to break into this world that was not available to them,” Young said.

“Even though there’s no blood relation, our characters are basically brothers. We are ride or die, I have his back, he has my back the entire way. … You bring other people that have been ostracized and shut out from this world together and create this brotherhood.”

Together, they spit rapid-fire dialogue like David Mamet’s “Glengarry Glen Ross” (1992).

“[Akhtar] referred to it as a Mametian Shakespeare play, meaning of the world of David Mamet and William Shakespeare,” Keegan said.

“We have a lot of fast-paced, quick, brilliant people who think as they speak, so it’s very exciting to watch them work through problems. Then you have other big, broad ideas like Shakespeare that have to get projected out because they’re rhetorical and the heart of the play, so you get these two forces working in concert.”

Much of this quick-witted attitude comes from Akhtar’s own real-life personality.

“If you ever hear him talk he’s one of the most erudite, eloquent people you’ll ever hear speak, like he sat down and wrote what he’s saying off the cuff,” Keegan said, to which Young added, “It puts a lot of pressure on us as performers. When you’re walking in being the smartest person in the room, you have to act like it. You have to look like it. You have to speak like it. You have to be on your A-game at all points. There’s no rest within this show, it is a tornado.”

The layout of the theater also lends urgency to the two-hour sprint (with no intermission).

“We’re performing in the round, so we’re surrounded on all sides,” Keegan said. “We have four entrances and exits, and the set is very minimal, so the storytelling really relies on us. There’s a Sorkin-esque quality to it, we want to keep it moving, we want it to feel like a walk-and-talk.

“These scenes begin in flagrante, we’re in the middle of the scene when we start and there’s a sense that something just happened and that something will happen after. … Suddenly over on the other side of the stage are two new people in the middle of another conversation.”

Orchestrating it all is director Jackie Maxwell, who helmed Keegan in “Watch on the Rhine.”

“Many local actors say she’s on our Mount Rushmore of directors,” Keegan said. “She runs a meritocracy; it doesn’t feel like a dictatorship. She has the final say, but I always feel like my voice is heard. She has a way of speaking to each actor as an individual. … Anytime we talked about the play, we talked about the character that she and I were building together. … When she was critical, she was benevolently critical. There is a way to give criticism that keeps people’s feelings in mind. … I hope it never comes to it because I would follow her into hell.”

Maxwell casts D.C. vets like Ed Gero and Jonathan David Martin across newcomers like Young.

“She embraces the idea of a community show,” Young said. “She has so much to offer right when we walk in the door. She’s willing to hear your ideas and she wants the best production, whether it’s her idea, your idea or somebody else’s idea. She has given us a freedom that is pretty rare in the theater to bring our own ideas to the stage and watch them sink or swim.”

Some D.C. audiences may see themselves in the characters.

“There’s a lot of people who come up to us and say, ‘I was working these deals in the ’80s and early ’90s,’ so to give them a refresher of their life is wild,” Young said.

“It’s cyclical. … There’s bailouts and people are just getting slaps on the wrist — if that. Just fines, no jail time hardly. This story is the origin story of that and how these big banks were doing dirt behind the scenes. … There’s moments where you think, ‘Oh, he’s going to come down hard,’ and you don’t ever really get that. It’s the same way today when you see reports of that happening.”

Recent headlines include Netflix buying $2 billion in junk bonds to fund their next seven years of projects. Even if you don’t work in this sector, you were touched by the 2008 housing crisis.

“Tens of thousands of people took their lives because they lost their homes in 2008 because bankers broke the law — and those bankers haven’t gone to prison,” Keegan said.

“This is an American story about greed and excess and danger. … We just had a former Fed chair say that ‘capitalism is more important than democracy’ with a straight face. … The biggest problem our country is grappling with today is the economic disparity between the top and the bottom.”

Indeed, the idea of “too big to fail” is present throughout the play.

“Mike Milken did go to prison for two years and when he came out he had $2.1 million — you decide if that’s justice,” Keegan said. “It certain isn’t to the factory workers who lost their jobs in middle America because their companies were cut apart. … Wealth gives you the ability to buy yourself out of the responsibilities of citizenship but maintain all of the rights.”

Such questions of fairness are bound to captivate and challenge audiences.

“From the moment that you walk in that door, sit down and the play starts, it grabs you and does not release you for two hours,” Young said. “It’s this incredible whirlwind in a fast-paced world for a part of our culture that maybe only the top 1 percent really knows about. … You’ll come out smarter, savvier and with questions about where your own moral compass lies.”

Where better to do that than at the Arena?

“Arena is the center for American storytelling in Washington D.C. and I dare say the country,” Keegan said with local pride. “I think it’s the preeminent regional theater in the country.”

Find more details on the Arena Stage website. Hear our full chat with Keegan and Perry below: