WASHINGTON — He was just inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Now, hip-hop icon Tupac Shakur gets his long overdue biopic in the new movie “All Eyez on Me,” charting his meteoric rise and fall from street poet to rap martyr after his murder at the age of 25.

It’s been a rough ride out of the gate, as the studio opted not to hold advanced press screenings out of fear of negative reviews. This became a self-fulfilling prophecy to the tune of 22 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, but I’m here to tell eager viewers to “Keep Ya Head Up.” The film may feel superficial for outsiders — mostly older, whiter, non-fans of his music — but it’s just satisfying enough for 2Pac fans.

The movie opens with Tupac (Demetrius Shipp Jr.) growing up in 1970s East Harlem as the son of an activist mother Afeni (Danai Gurira) and stepfather Mutulu Shakur (Jamie Hector), both members of the Black Panthers. They move from New York to Maryland, where he attends the Baltimore School of the Arts alongside classmate Jada Pinkett Smith. But just as he’s landed the lead role in the school production of “Hamlet,” he’s uprooted again to Los Angeles, where he witnesses a murder on Day 1.

Like a “rose through the concrete,” Tupac rises from a background dancer for Digital Underground to a film actor in “Juice” (1992) to a record deal with Interscope. As we chart his smash success selling over 75 million records, we also see the dangers that thwart his potential, from his sexual assault conviction (he maintained his innocence), to the shooting that sparked East Coast vs. West Coast (he believed Biggie & Puffy set him up), to his drive-by murder on that fateful night in Las Vegas in 1996.

The film works to the extent that it does thanks to a sympathetic performance by Demetrius Shipp Jr., who not only looks the part but whose father co-wrote Pac’s “Toss It Up” for “The Don Killuminati: The 7-Day Theory.” The posthumous album fueled Elvis-style conspiracies that 2Pac was still alive somewhere cranking out albums, and just to look at Shipp Jr., you’d swear he’d come back on screen.

Thankfully for viewers, Shipp Jr. leaves the singing portions to 2Pac himself, mouthing the lyrics as the soundtrack plays the original tunes. Time and again, 2Pac’s own words detail his character arc, from the son of a drug addict (“Even as a crack fiend, mama, you always was a black queen, mama”) to his post-jail explosion of pent-up creativity (“Out on bail, fresh out of jail, California dreaming!”).

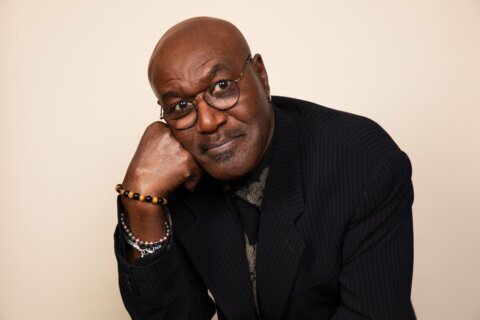

Co-written by screenwriting duo Jeremy Haft and Eddie Gonzalez (TV’s “Empire”) from an original draft by Steven Bagatourian (“American Gun”), the script relies heavily on its framing device of 2Pac granting an interview to a journalist (Hill Harper) while jailed at the Clinton Correctional Facility. Like Billy Crudup interviewing Natalie Portman in “Jackie” (2016), it proves a double-edged sword here.

On the one hand, it allows the journalist to address concerns by critics of gangster rap. “You’re trying to start a positive movement by using negative symbolism like ‘thug,'” the journalist says. Pac replies, “You’ve got to enter into somebody’s world in order to lead them out.” This is a clever bait-and-switch, allowing Pac to provide some context that “THUG LIFE” is actually a socially-conscience acronym: “The Hate U Give Little Infants F***s Everyone,” tying perfectly into his first hit “Brenda’s Got a Baby.”

On the other hand, the framing device of Pac behind bars keeps an unfortunate reminder of his 1994 sexual assault conviction hanging over the entire film. It’s not quite the same as watching Nate Parker in “The Birth of a Nation” (2016) or Casey Affleck in “Manchester By the Sea” (2016), but it has a similar effect. That is, unless you believe Tupac’s claim that he was sleeping in the other room when the accuser barged in claiming she was raped by his associates, only to pin it on him in a public trial.

It’s a case of “he said, she said,” as Tupac told Arsenio Hall that he was stunned that “a woman would accuse me of taking something from her.” Diehard fans were inclined to believe him considering that just a month before the charges, Tupac penned rap’s ultimate defense of women in “Keep Ya Head Up” with the lyrics: “Since we all came from a woman, got our name from a woman and our game from a woman; I wonder why we take from our women, why we rape our women, do we hate our women?”

Ironically, the women in his life provide the film’s moral conscience. First, it’s mother Afeni, whose political aptitude earns his respect. Later, it’s Pinkett Smith (Kat Graham), who urges him to aim higher than violent lyrics, despising his dis record “Hit ‘Em Up.” Finally, it’s Quincy Jones’ daughter Kidada (Annie Ilonzeh), his fiance left waiting at a Las Vegas hotel on the night of his drive-by death.

As Tupac and Kidada stand on opposite sides of a hotel door for a doomed “should I stay or should I go” dilemma, it’s an intimate moment that feels either forced or fabricated. The same goes for a balcony scene where Pac & Biggie look over the city and comment on the impact of their music. The dialogue is very on-the-nose compared to a similar scene between Avon & Stringer in “The Wire.”

Such moments may have been better captured by Antoine Fuqua (“Training Day”) or John Singleton (“Boyz N the Hood”), who both left the project over creative differences, leaving directing duties to Benny Boom (“S. W. A. T.: Firefight”). While his feature films aren’t exactly acclaimed, he’s directed a string of successful music videos: Nas’ “Made You Look,” 50 Cent’s “Just a Lil’ Bit,” P Diddy’s “I Need a Girl,” Akon’s “Smack That,” Nelly’s “Dilemma,” T-Pain’s “Buy U a Drank” and Ciara’s “Goodies.” That’s a nice track record for one medium, but it doesn’t always translate for two-plus hours of a feature film.

At times, “All Eyez on Me” plays like a TV movie, skipping across the surface from one event to the next, rather than digging deep. It pales in comparison to an Oscar contender like the N.W.A. biopic “Straight Outta Compton” (2015), instead feeling more like the Biggie biopic “Notorious” (2009), whose star Jamal Woolard returns here. While Corey Hawkins and Lakeith Stanfield were a better Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg in “Compton,” Dominic L. Santana is a scarier rendition of villain Suge Knight.

Knight is chilling as he gathers his employees around a table to set a violent example like Al Capone in “The Untouchables” (1987). As Tupac sells his soul to Knight’s Death Row Records in exchange for bail money, we understand our hero’s motives to pay off his legal debts. But as he gets in deeper and deeper, we realize that there’s no escape, a tragic fall to martyrdom marked with crucifix symbolism.

Thus, the film’s best moment is a subtle one, as Knight glances suspiciously to the left of the frame as he and 2Pac pull up to the fatal stoplight. This, combined with his exploitation of posthumous albums, fuels fodder for Makaveli conspiracies and documentaries. The best of these is Lauren Lazin’s Oscar-nominated “Tupac: Resurrection” (2003), a must-watch film where “Hail Mary” makes a much more haunting climax than Boom’s “So Many Tears,” all capped by a transcendent “Until the End of Time.”

If you haven’t seen “Tupac: Resurrection,” you’ll definitely want to check it out first (“run-quick-see!”). Then, after you’ve watched it, check out “All Eyez on Me” as a decent but flawed companion piece that at least brings to life what has previously only been archival footage. Which brings us back to the 22 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, suggesting a failing “F” grade when the Cinemascore audience poll is an “A-.” In truth, it’s somewhere in the middle, a solid “C” take on an “A+” career for rap’s best emcee.

So while fans will enjoy seeing the film check all the boxes, the superficial treatment won’t win any converts, which is a shame because everyone ought to explore this man’s tormented genius. As Tupac said, “I’m not saying I’m going to change the world, but I guarantee I’ll spark the brain that will change the world.” Likewise, this movie won’t change film history, but it could spark a brain to do it better.