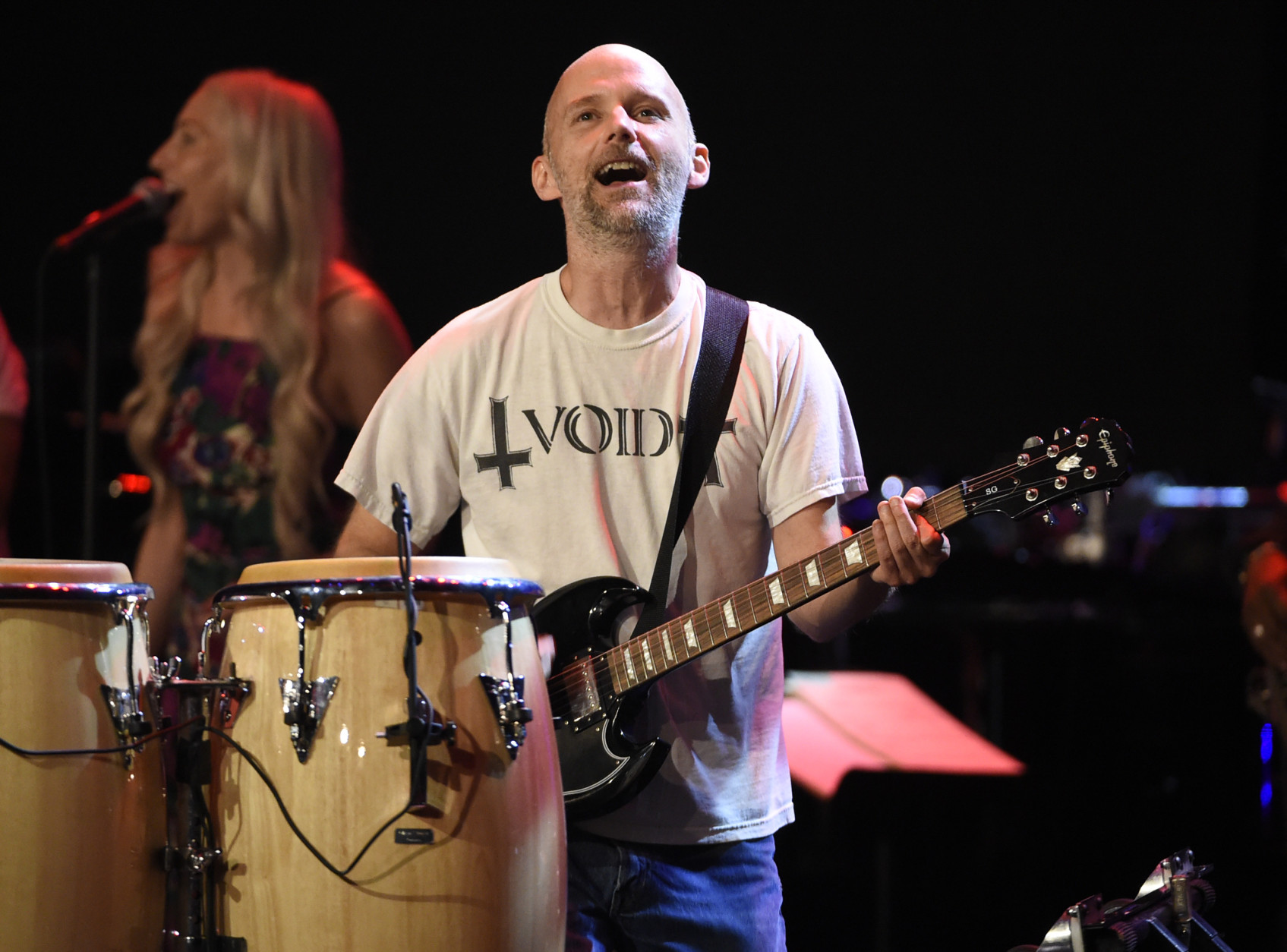

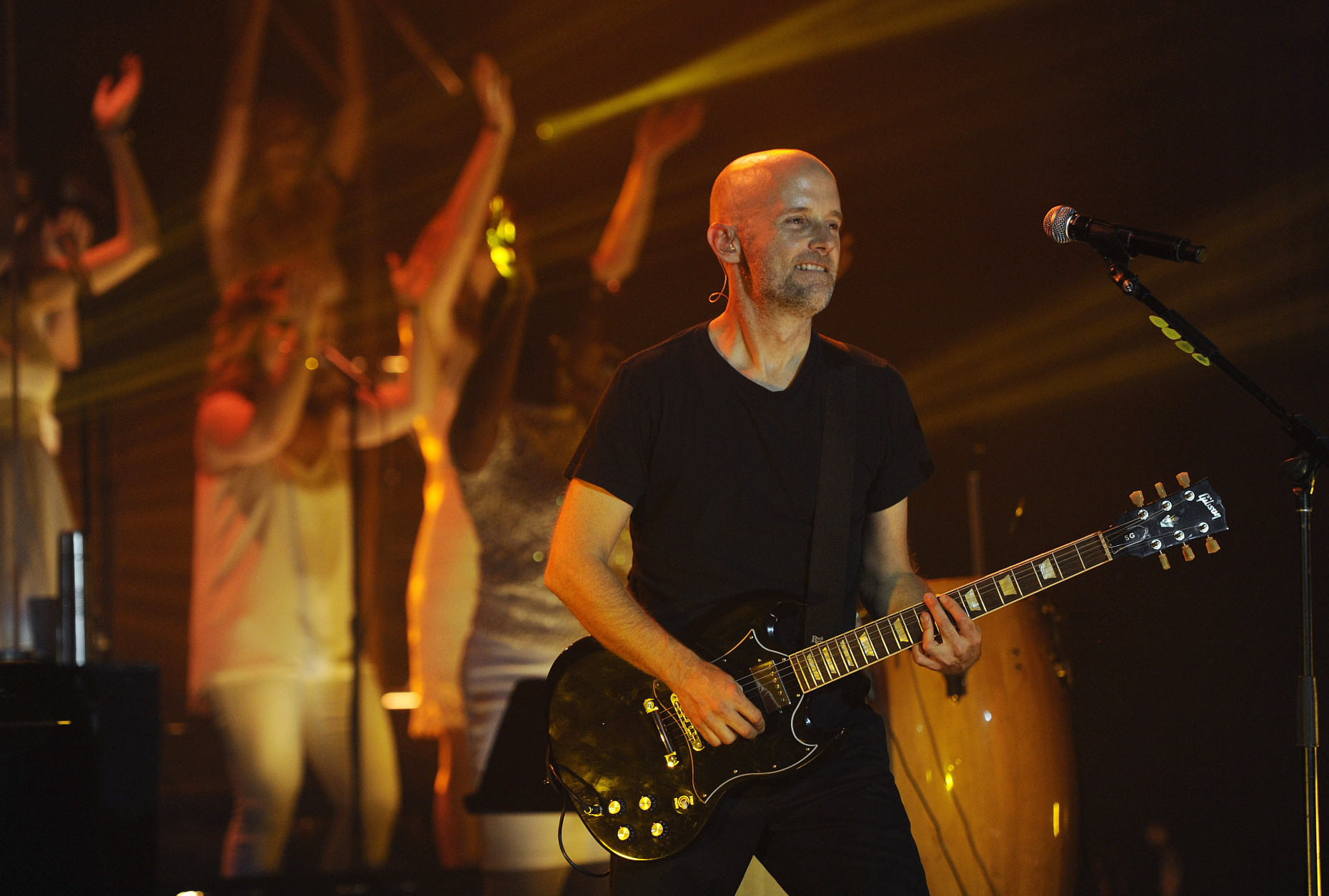

WASHINGTON — One of the most influential figures in the brief history of techno music is offering a rare glimpse into what makes him tick.

The ever-versatile Moby chronicles his unique life and career in the new memoir “Porcelain.”

“It’s a memoir, but it’s also very much about the sort of evolution of New York from 1989 and the world of dance music and the world of electronic music,” Moby told WTOP.

“This archetypal story of a young, naive kid moves to the big, dirty city and largely gets destroyed.”

This “young, naive kid” was born Richard Melville Hall, named in part after his distant relative Herman Melville, author of “Moby Dick.” Forget, “Call me Ishmael.” Call him Moby.

“When I was born my dad looked at me and thought that Richard Melville Hall was far too adult a name for a tiny baby, so as a joke, he started calling me Moby,” Moby said.

“Now, 50 years later, I’m still saddled with my infant joke nickname.”

Growing up in Harlem then Connecticut, Moby’s shifting environment helped inform his worldview.

“Socioeconomically, I had a very strange childhood,” he said. “I was the only child of a single parent. I was born in Harlem, then at some point in childhood, my mom moved us back to Darien, Connecticut … one of the most affluent places on the planet. … [We] were on food stamps and welfare, so it was really odd being dirt poor in what is arguably one of the wealthiest places in the world.”

After these formative years, we reach the time explored most heavily in the book, Moby’s young adulthood as he left his humble roots and dove headfirst into New York’s wild music scene.

“The book covers my life from 1989-1999. In 1989, I was living in an abandoned factory and I was making $3,000 a year. I didn’t have running water, I didn’t have a bathroom and all I wanted in life was to get a record deal and to be able to DJ in New York.”

When both of these goals came true, Moby had an eye-opening experience:

BOOK EXCERPT: “The record stores were owned by the people who made and played the records. The clothes were made by friends of the people making records. The drugs were sold by roommates of the people making clothes and records. Every night people were dying on the streets and New York City was literally setting itself on fire: landlords had learned that it was cheaper to burn down empty tenements than to pay taxes on them. And somehow the collective response of anyone in their twenties living south of Fourteenth Street was to ignore the despair and the fear and to go dancing until five a.m.”

The theme of the book plays upon a unique moral juxtaposition.

“I was part of the rave scene and club scene, but I was also a sober Christian,” Moby said. “For the first half of the book, I’m this sober Christian in degenerate, crack-addled, gang-violent New York. … At night I would be DJing at raves and sex clubs, but then during the day I’d be teaching Bible studies.”

Soon, his lifestyle shifted entirely in the bohemian, hedonistic direction.

“Halfway through the book, I go to the other extreme of being this crazy, dysfunctional drunk.”

That’s precisely where he came up with “Porcelain” — a book title with multiple meanings.

“The book is called ‘Porcelain’ for three reasons,” Moby said. “One, it’s the name of one of my better-known songs. Two, porcelain is white and fragile, and in the book, I’m white and fragile. And [three], as I mention halfway through the book, I relapse and start drinking again. To be honest with you and a little graphic, I do a lot of throwing up by the porcelain toilet, so as a title, it just sort of makes sense.”

Might we suggest a fourth layer of meaning: that of a porcelain religious madonna, the type that Paul Newman sang so hauntingly about in “Cool Hand Luke” (1967). Moby has a similar journey as the titular Luke, a rebellious nature and a crisis of faith before reaching an ultimate clarity by the end.

Where does Moby stand today spiritually?

“We live in a universe that seems to be 15 billion years old, so as much as I love the teachings of Christ in the New Testament, I also love Taoism and Sufism and Quantum Mechanics,” Moby said.

Regardless of your religious perspective, Moby’s journey makes for a fascinating character arc, fledgling through four under-the-radar albums — “Moby” (1992), “Ambient” (1993), “Everything Is Wrong” (1995) and “Animal Rights” (1996) — before reaching his so-called Dark Night of the Soul.

“I made a record no one liked and lost my record deal. My mom got very sick and died. So by the end of the book, my life has basically fallen apart, and the book ends the day before I released the album ‘Play.’ So I thought my career was over … but it turns out things worked out interestingly after.”

“Play” was certified platinum in more than 20 countries, became Britain’s top-selling indie album of 2000 and recently ranked No. 341 on Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, writing:

‘Play’ was the techno album that proved a Mac could have a soul. Moby took ancient blues and gospel voices and layered them with dance grooves, on songs such as ‘Porcelain’ and ‘Natural Blues.’ This was an album with a strange, haunting beauty — especially for advertisers, who mined Play for countless TV commercials.

The album also earned a pair of Grammy nominations for Best Alternative Performance (“Play”) and Best Rock Instrumental (“Bodyrock”), accolades that Moby admits he was shocked to receive.

“It was originally supposed to fail, but it just kept doing better and better and ended up selling over 10-million records,” Moby said. “I really thought I was gonna release ‘Play’ and no one was going to listen to it and I was gonna end up teaching community college in Connecticut and continuing to make music … so when it ended up being successful, it was very very baffling and surprising to me.”

The album’s biggest radio hit was hands down “South Side,” a duet with Gwen Stefani that reached No. 14 on the Billboard Hot 100 — a rare feat for a guy who often places on the U.S. Dance charts.

“‘South Side’ was such an odd hit single because it actually was a song written about a dystopian, post-apocalyptic future wherein life had ceased to have much meaning,” Moby said. “I thought it was very odd that it went on to become a Top 40 single because the subject matter really is not the sort of subject matter that tends to lend itself to Top 40 singles.”

To date, Moby has landed six Grammy nominations for his music, though many folks likely know his sound from the movies. His instantly recognizable jam “Extreme Ways” serves as the theme to the “Bourne” franchise starring Matt Damon. Just like John Barry and Monty Norman are tied with their signature “007” theme, Moby is forever tied with Jason Bourne for his badass “Bourne” theme.

The fifth installment, “Jason Bourne,” is set to hit movie theaters on July 29.

“I’ve seen a rough cut of it, and honestly, it’s really special,” Moby said. “Matt Damon is back involved, as is (director) Paul Greengrass, and it’s really exciting. I’ve done the closing credits for that as well.”

Film scoring has become a bit of a passion for Moby, who launched the website MobyGratis.com, which provides royalty-free music for independent and nonprofit filmmakers. The site features more than 150 tracks from Moby’s music catalog available to license for free via an online application.

“When I was in college, I was a philosophy major, but I had a lot of friends who were independent film students and they found it really difficult to license music for their movies,” Moby said. “So I started this website MobyGratis.com to just give free music to film students and independent filmmakers and documentary filmmakers just as a way to try to help them out with what is a really difficult process.”

From indie films to blockbuster movies, Moby does it all, dabbling in a range of musical genres.

“My background as a musician is very odd,” Moby said. “When I was very young, I played classical music. Then I played in punk rock bands and I was a hip-hop DJ for a while, so I love electronic music. But from my perspective, it’s one genre that I like to play around with, but one genre among many.”

Of course, he’s most often associated with the techno genre, which began a bit of a beef with the always controversial Eminem. The rap emcee infamously slammed Moby in his 2002 song “Without Me,” rapping: “Moby, you can get stomped by Obie … Let go, it’s over, nobody listens to techno!”

While Eminem has defied detractors’ criticisms to become one of the greatest social rappers of all time, it seems Moby has gotten the last laugh when it comes to the popularity of house music.

“It was funny for Eminem to say nobody listens to techno, and now you have events with 100,000 people in a sports stadium dancing to electronic music. Clearly, I guess people do listen to techno,” Moby said. “Eminem is a smart, very talented musician. I wish him well and hope he’s doing OK.”

That’s not a sidestep answer as much as it is a credit to Moby taking the high road. It’s the same sort of introspective tone revealed in the book, a self-deprecating reflection on his own personal demons.

“[After having success], I went down this other rabbit hole of constant touring, entitlement, narcissism and really unpleasant self-importance,” Moby said. “That just got worse and worse and worse until I finally had to stop drinking altogether in 2008. … Today I’m a middle-aged sober guy.”

Praise the Porcelain God.

Here’s more information on the “Porcelain” memoir. Listen to the full interview with Moby below: