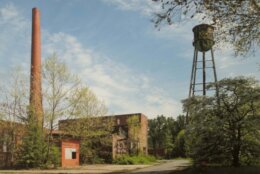

WASHINGTON — Ivy, graffiti and rot adorn the abandoned walls of Glenn Dale Hospital and Sanatorium. The 200 acres of land 15 miles outside D.C. have inspired countless ghost stories and conspiracy theories.

Locals know all about “The Goatman” who roams the woods of Prince George’s County, or the escaped inmates that haunt the halls of Glenn Dale.

Unfortunately for thrill-seekers, none of these rumors are true.

Glenn Dale opened in 1934, during the height of a tuberculosis epidemic that hit the capital region especially hard. Hospitals within the District were overwhelmed, so patients were shuttled to the outskirts of the city to rest and, eventually, die.

At the time, hysteria and fear dominated the country’s response to the so- called “white plague.” Sunshine and vitamin D were some of the best defenses against TB, so Glenn Dale was designed with the outdoors in mind.

The 23-building campus is situated among the rolling hills and grassy meadows of what used to be rural Maryland. There were separate buildings for children and adults, as well as for nurses and doctors. There was a solarium, laundry room, morgue, drawing rooms, outdoor gardens and indoor hothouses to grow vegetables.

Many of the buildings were designed by Nathan C. Wyeth, the same architect responsible for the Key Bridge, the original Oval Office and a number of other municipal and federal buildings in the area.

At its height, Glenn Dale housed about 600 patients and 500 doctors and staff members.

“In those days, people were afraid of tuberculosis because they didn’t know much about it,” says Kira Calm Lewis, a spokeswoman for the Prince George’s County Department of Parks and Recreation.

“Patients diagnosed with TB were cast off from society. Their families wouldn’t tell people where their relatives vanished to.”

In 2006, a Washington Post reporter shared her mother’s story about life within Glenn Dale. The young mother was 27 at the time and nine months pregnant with the author, Leah Latimer, when she experienced shortness of breath while walking up the stairs.

Despite not showing any signs of TB — fever, night sweats or coughing up blood — the doctor sentenced Etta Frances Young to treatment at the sanatorium.

“Mama sobbed in her hands and wailed about her three little girls. Just the letters ‘TB’ stunned her. Not long before, an uncle with TB had been sent to a sanatorium. Two childhood classmates, brothers, got sick with TB after they moved to the city, and died at Glenn Dale,” Latimer wrote.

Because tuberculosis was seen as a death sentence, it bore a heavy stigma. Families shunned relatives with the disease, and treatment eluded the medical community for generations. At best, TB patients were sent somewhere comfortable to die. At worst, they were experimented on and treated with ethically questionable methods such as collapsing the infected lung.

This stigma has likely contributed to the urban legends surrounding Glenn Dale, Lewis says.

“There was a such a lack of information at the time,” she says.

Tuberculosis, or consumption as it was known, is a respiratory disease that can be highly contagious, especially among people living in close quarters. Untreated, the infection can cause bloody coughing, painful breathing and severe fever and fatigue. It is caused by bacteria lodged in the major organs, but typically affects the lungs. It can now be treated with harsh antibiotics that must be taken for up to nine months.

“There was a huge stigma surrounding TB, so they kind of isolated the patients,” Lewis says. “No one spoke about having tuberculosis.”

By the 1950s, the number of TB cases declined, and Glenn Dale slowly started to empty. In the 1960s, the campus opened up to include indigent patients. It remained a nursing home until the campus closed because of asbestos in 1982.

“Glenn Dale was never a home for the insane. It was never a prison. It was always a hospital,” Lewis says.

But it has nevertheless become a playground for teens, ghost hunters and other urban adventurers. Lewis says trespassers are frequently escorted off the grounds, especially during Halloween season.

“Teenagers dare each other to see who can get on the property,” she says.

Officials have been approached by film crews and researchers eager to hints of creepy, spooky or unearthly beings lurking inside the halls of Glenn Dale. Despite the intense supernatural interest, Prince George’s County is focusing on finding a buyer for the abandoned campus.

Glenn Dale now belongs to the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, which purchased the hospital from the District of Columbia for $4 million in 1994. In 2011, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Lewis says finding the right buyer has been painstakingly slow. The county issued a request for proposals, but no developers were able to meet the criteria set aside in 1995, which requires that a majority of the property be set aside for continuing care or to serve as a retirement home.

“It’s a prime location,” Lewis says. “We want to find a developer that will make good use of this land.”

But first, the rubble must be cleared, buildings need to be stabilized and asbestos has to be removed. In 2015, the land was cleared of some trees and debris, and grass was cut back. Lewis says security cameras are also being installed on the property.

The project is so immense that Prince George’s County is still pricing the partial restoration of Glenn Dale.

Until then, the former hospital remains a ghost-hunting destination:

Follow @WTOP and WTOP Entertainment on Twitter and WTOP on Facebook.

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on Oct. 8, 2014. It has been updated to reflect the current status of the property.