D.C. should establish a commission for a one-year study on the many possible effects on the city of on-demand, ride-hailing services, such as Uber and Lyft, Georgetown University researchers warn.

“This study offers more questions than answers,” said Katie Wells, a postdoctoral fellow with Georgetown’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor.

“What are the effects of the ride-hailing industry on the city’s workforce, on transportation equity, on the disability rights community, on pollution, on the environment? There’s a host of questions we don’t have answered,” Wells said.

D.C.’s government has to take steps, Wells said, much like New York City did, to evaluate those issues before “we hand over the keys to the city to (these) private companies.”

One issue of particular concern identified in the study is how the workforce that provides the service is being affected.

“Our study suggests that there are good reasons to be concerned about this workplace,” Wells said. “If there’s someone you care about, please help them find a different job.”

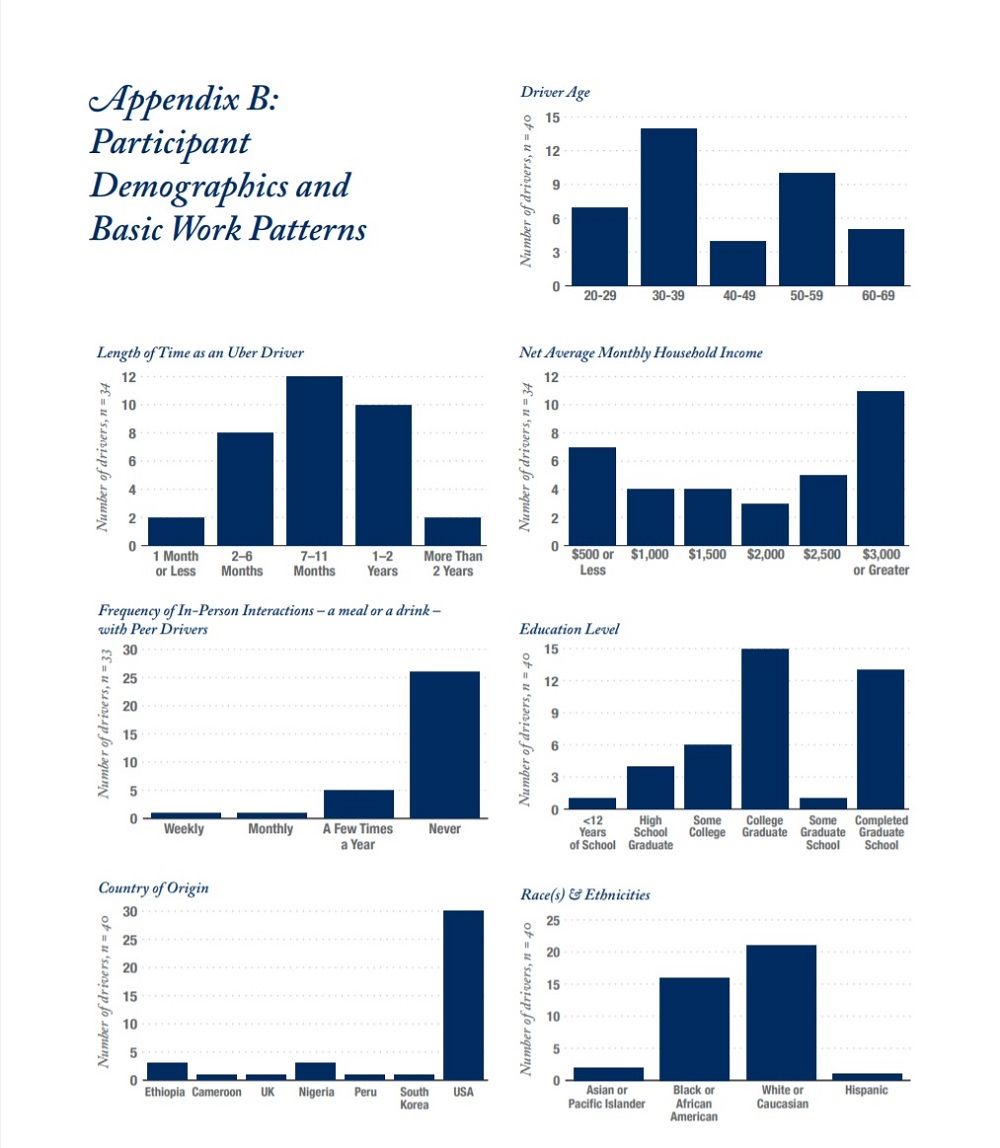

Study authors want to know whether, or to what degree, the ride-hailing industry conforms to contemporary labor standards. Wells said that the 40 drivers in the study might not necessarily reflect what’s happening throughout the industry.

“It may be that these are good jobs, We just don’t have the data to suggest it. And no policy makers can figure it out either. And that’s a problem,” she said.

The ongoing study will follow 40 drivers for five years. Researchers compiling findings from the study’s first two years were surprised, Wells said, that every driver faced barriers when trying to figure out how much money they were making.

“The best estimate that we have come across is that drivers need 20 different individual pieces of information to calculate their wage,” Wells said.

As independent contractors, the drivers have to figure out how much they’ll pay in income taxes at the end of the year. Then, there’s gas, vehicle maintenance, car payments, vehicle depreciation, tolls and unpaid time spent and distance traveled to get to or from riders who are provided service, or drivers waiting around for calls for service.

A spokesperson from Uber said that the company has made changes that benefit their drivers that are not yet reflected in the data.

“Uber has changed a lot since this research was started,” the spokesperson said. “Driver-partners are the heart of our service — and Uber would not be what it is today without them. Building on what we’ve already introduced, like in-app tipping, a redesigned driver app, Instant Pay, and new rewards programs like Uber Pro, we’ll continue to improve the experience for and with drivers, every day.”

Other study findings:

-

- 30% of Uber drivers reported safety concerns or physical assaults.

- 33% of drivers took on debt for their work with the Uber platform.

- 50% of Uber drivers would recommend the job to a friend.

- 45% of drivers planned to keep working the job for at least six more months.

The study finds that drivers for ride-sharing services might be at risk of being exploited.

“This emerging set of research suggests that digitally mediated labor platforms, the most visible of which is Uber, are part of a long-term erosion of worker rights and an ongoing shift of risk from employers to low-wage workers,” the study said.

This article has been updated to include Uber’s response to the initial findings of the study.