WASHINGTON — It’s no secret the D.C. area is home to some pretty terrible traffic. But now, there’s evidence that a long, complicated commute could be holding you back from a new job.

A new first-of-its-kind study out of Notre Dame University found some D.C. employers discriminate against applicants with long commutes — and that the effects are significant.

Researchers, led by Notre Dame economics professor David Phillips, sent out hundreds of fictional resumes — with real addresses from across D.C. — to apply for primarily low-wage positions in the center of the city. All else being equal, hiring managers were 14 percent less likely to call back applicants living further away from the job than those with nearby addresses, according to the study, which is set to be published in the Journal of Human Resources.

For every mile away from the job an applicant’s address was, the percentage of callbacks from interested employers fell by more than 1 percentage point, according to the study.

Previous studies have found employers can be influenced by the address on jobseekers’ resumes. But Phillips said his study is the first to pinpoint that hiring managers may be more influenced by sheer distance from the job as opposed to simply discriminating against applicants from poorer neighborhoods.

“I think this is the first one to say, ‘Hey, if employers are responding to addresses … here’s an explanation for why it could be about commute distance as opposed to necessarily about the affluence of the neighborhood,'” he said.

How the study worked

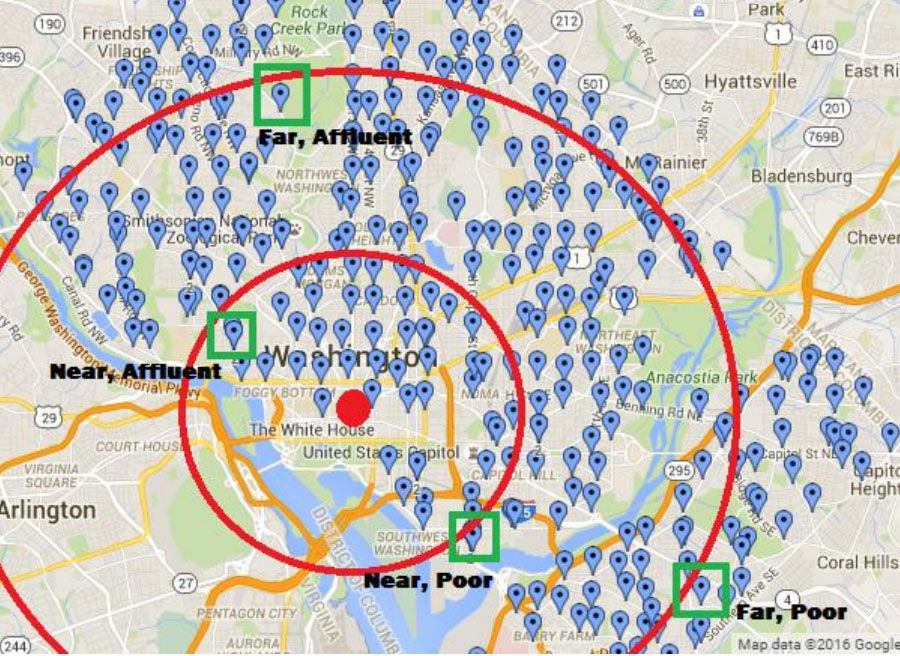

Here’s how the study worked: The research team sent out more than 2,200 fictional resumes to mostly low-wage job openings in D.C., such as administrative assistant, cook, retail sales clerks, restaurant server and valet driver. The resumes were nearly identical in terms of education levels and past work histories, but contained different addresses.

For each job opening, the team picked addresses in neighborhoods that were similar in terms of education, income and racial composition but that would have different commute lengths to the job.

The goal was to make an apples-to-apples comparison.

Rather than comparing an address from the Northeast neighborhood of Deanwood with the tonier Dupont Circle in Northwest, the study compared Deanwood with Trinidad, which is similar socioeconomically but closer to downtown jobs.

“And so that’s how we tried to pick apart: Is this about commuting distance, per se, or is it about the affluence of the neighborhood? It looks like what employers were really responding to was distance, even if you keep the affluence of the neighborhood similar,” he said.

But, why are employers discriminating against potential employees with long commutes? Previous studies have found that employers are concerned that long commutes hurt workers’ productivity, and there is actually some evidence to back that up. One previous study found that reducing average commute times cuts back on employee absence rates.

In addition, many low-wage workers in D.C. commute to work via bus, which can often be more unpredictable and less reliable than driving or taking Metro — something D.C. employers may be aware of.

Whatever the cause, hiring managers’ bias against potential workers with long commutes has broad social implications, Phillips said, helping deepen patterns of residential segregation and “perpetuating poverty in particular places,” he said.

“So the employer starts with that: I’m going to hire people that live close” to jobs, Phillips said. “And then, the thing that feeds into that is that different groups of people are more likely to live close to jobs.”

In D.C., for example, the average black person lives about a mile farther away from the type of low-wage jobs included in the survey than the average white person does, he said.

While the study itself was confined to the borders of D.C., Phillips said the results likely resonate across the region.

“In the study, we’re looking at differences of a couple of miles, and those matter because people are taking public transit and it takes a while to go over that distance,” Phillips said. “But, if you start imagining somebody taking two, three buses to get out to their address in (Prince George’s) County, or they’re going across one or two state lines, you could imagine that this becomes even more of a thing.”

Phillips said his study doesn’t propose any solutions but that discussions about transportation and housing are natural starting points.

“If employers are concerned about employing somebody who lives farther away because they’re concerned that they can’t get to the job, then we want to start thinking about, ‘OK, how can we facilitate transportation for that person?'” Phillips said. “How could public transit be better?”