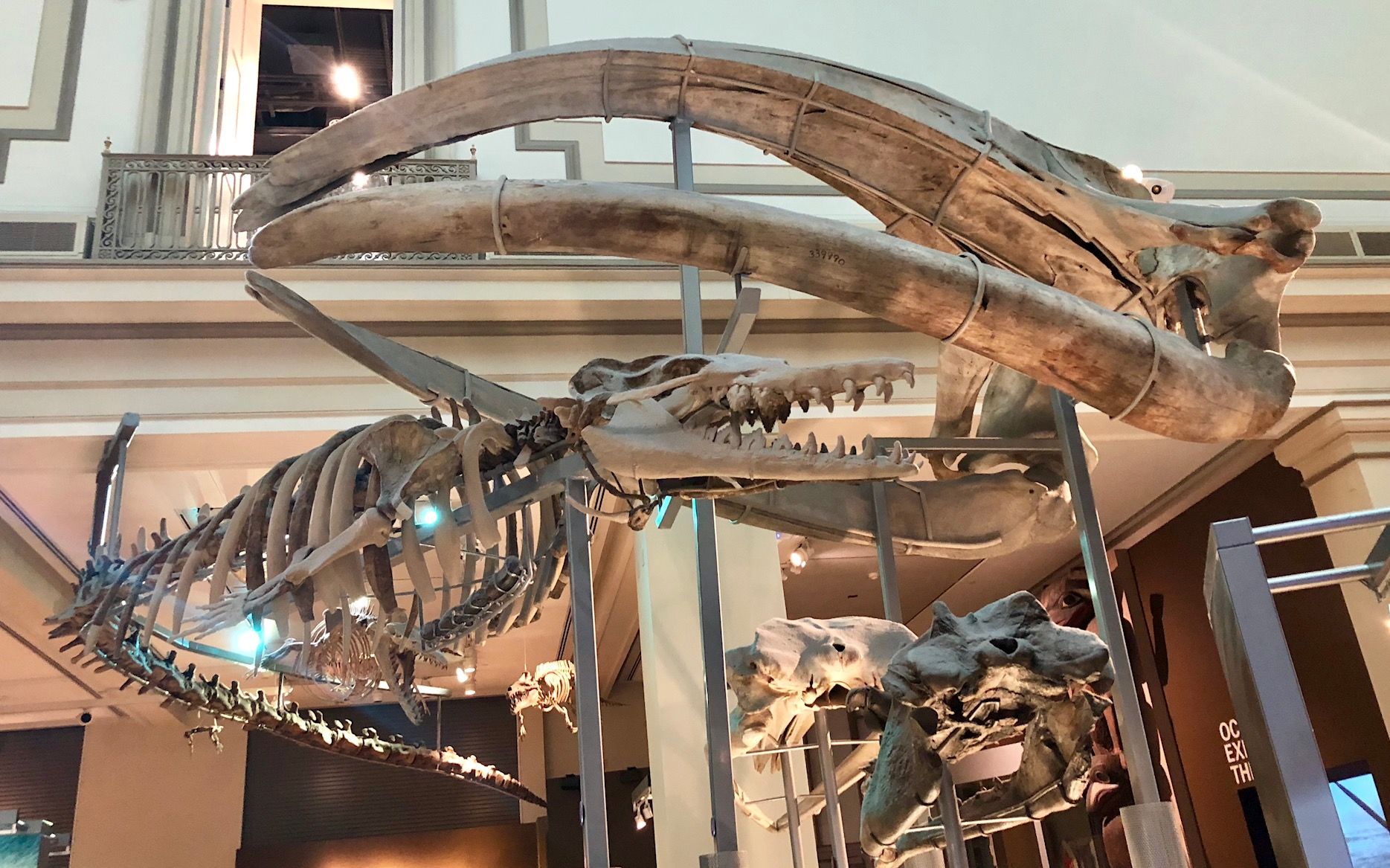

WASHINGTON — In less than a year, the Smithsonian unveils its much-anticipated fossil hall, featuring the return of the Tyrannosaurus rex. Debuting alongside the daunting dinosaur are the fossils of prehistoric whales, whose descendants grew to be the largest animal the planet has ever known.

Curators are in full preparation mode for the opening of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History David H. Koch Hall of Fossils in June 2019.

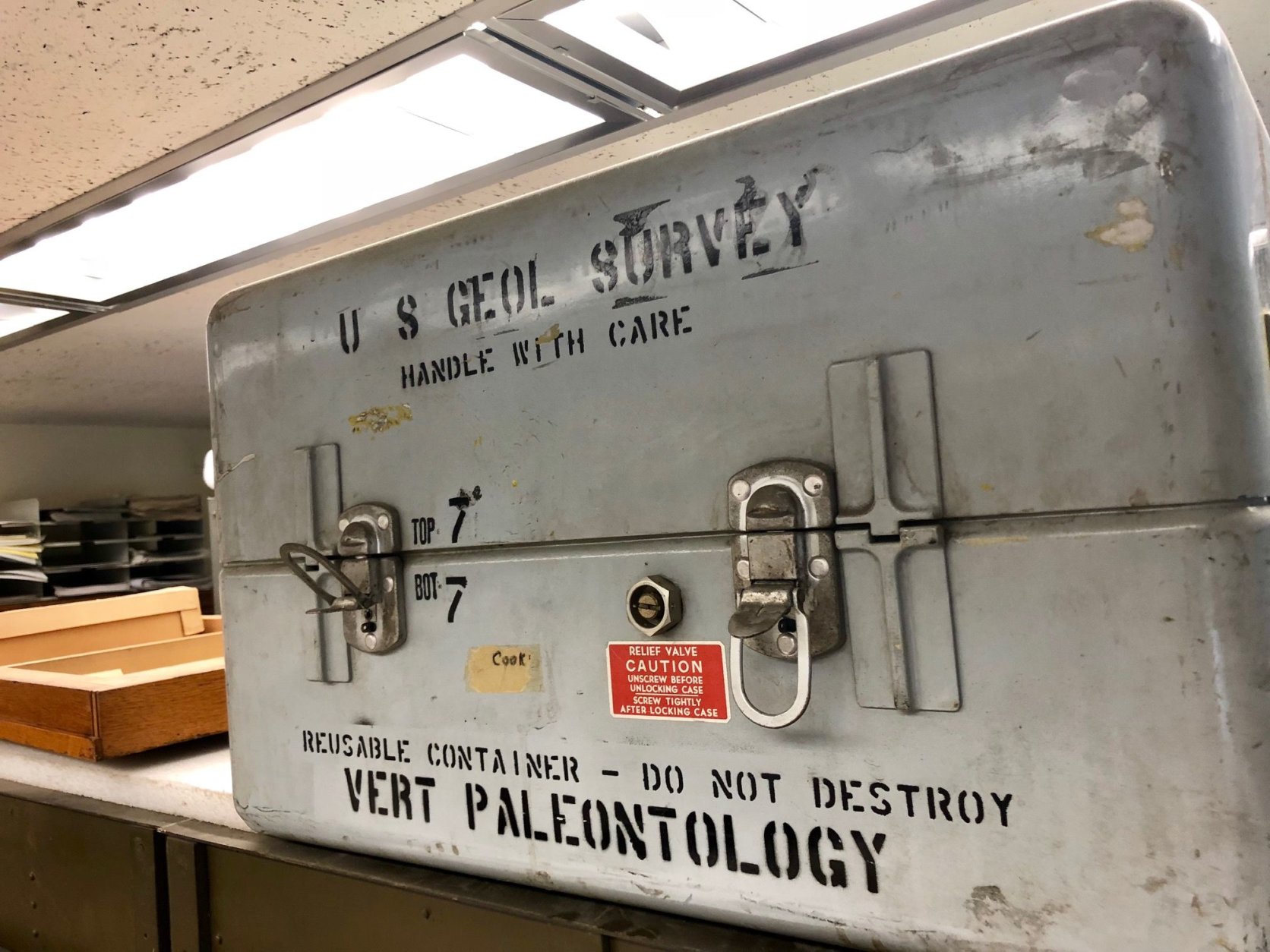

In a massive storage room inside the museum, partially constructed fossils, rare crystals and rows upon rows of large crates wait to make their way into what will be a 31,000-square-foot space.

“The scale of what we are setting out to do is easy to communicate but much different when you see it in person. It’s nearly a quarter of the first floor of the museum,” said Nick Pyenson, as his keycard zips back on its line and the door to the fossil room unlocks.

Pyenson is the Smithsonian’s curator of fossil marine mammals and part of the team that reimagined its fossil hall, which has been closed since 2014.

Set aside the fact that Pyenson studies, collects, compares and constructs marine fossils for a living. Just the fact his badge allows him access to the temperature-controlled fossil room at the nation’s Natural History Museum would make any nerd’s jaw drop. It did mine.

I catch a glimpse of a 7-foot tall dinosaur fossil silhouette. I feel like this is when Willy Wonka opens the door to the chocolate factory.

“It’s even better,” he replied.

More than dinosaurs

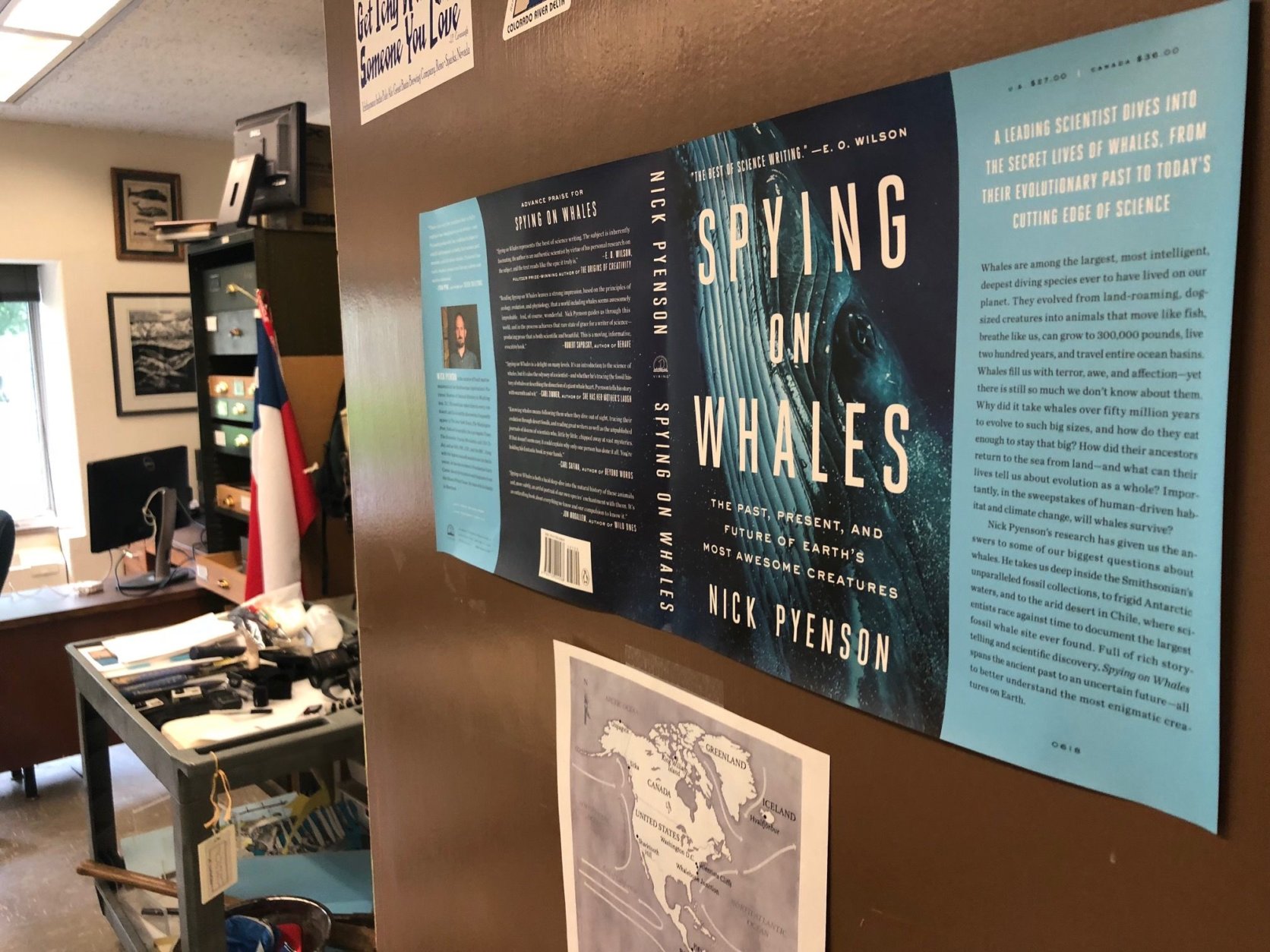

While there has been much ado about the unveiling of the T. rex, Pyenson’s passion lies with a 50-million-year-old mammal; cetaceans. He just authored a book, “Spying on Whales: The Past, Present, and Future of the Earth’s Most Awesome Creatures.” It tells the scientific story behind their evolution, their extreme biology and their complicated relationships with humans.

“We live in a time of giants. Never before in Earth’s history have we had whales this large, and actually mammals this large. These are the largest vertebrates of all time,” he said.

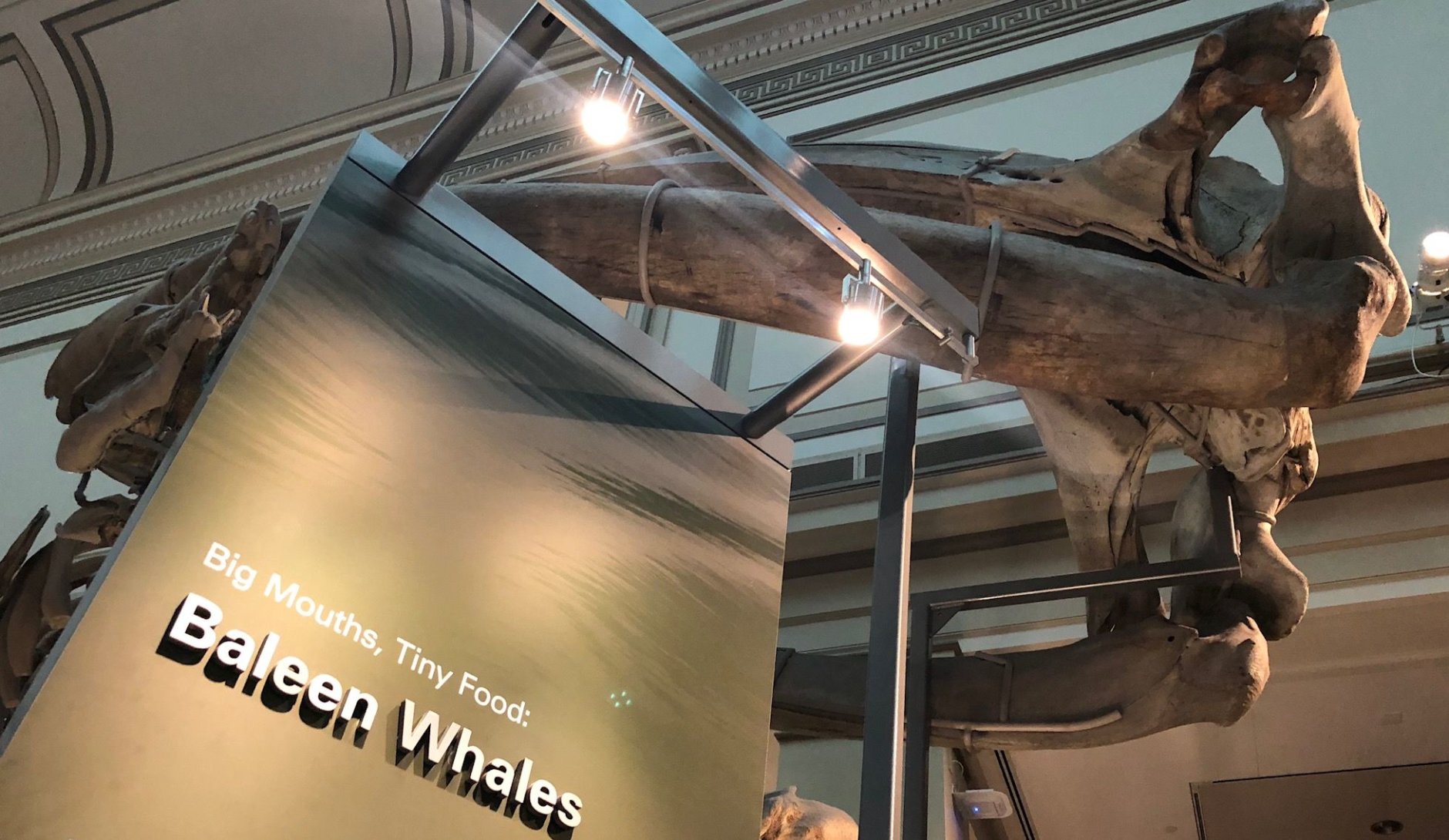

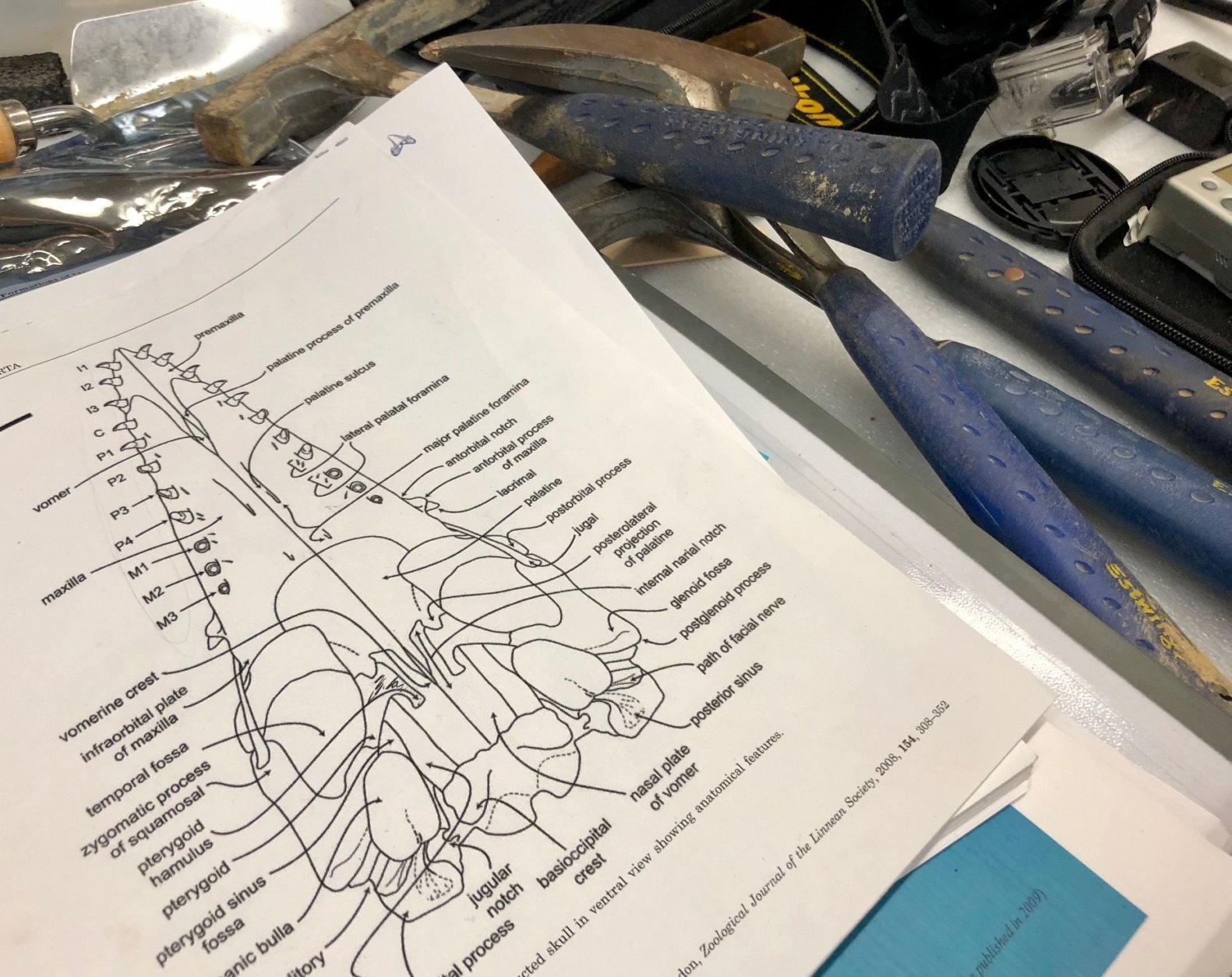

Next summer, visitors to the museum’s new hall will also see the skull of Odobenocetops, a walrus-like whale with one elongated tusk. It is roughly 52 million years old and from South America. Also on display will be a fossil baleen whale called Diorocetus; a distant relative of humpbacks, unearthed locally.

“They are fossil whales from Calvert County (Maryland) — actually from Calvert Cliffs — that have been collected some 60 to 80 years ago. … One of the key things about them, they look not too dissimilar from living whales. They are only about 14 million years old,” Pyenson said.

The incorporation of the whale collection into fossil hall has a lot to do with visitors’ seemingly insatiable interest in the mysterious mammal. Like humans, Pyenson explains, whales are either right- or left-handed. Not all whales use echolocation to find prey, and they turn off half of their brains when they sleep. Depending on the individual, scientists can tell how old whales are by their teeth, eyeball and sometimes the rings in ear wax — similar to reading tree rings.

“Whales had land ancestors, and they had toes that ended in hooves probably,” he says. “Over time, whales lost their hind limbs and lost the ability to use their limbs on land, and those limbs transformed into flippers.”

A ‘rodeo at sea’

In “Spying on Whales,” Pyenson writes about a scientists’ “rodeo at sea” and his success in tagging a humpback whale with a suction-cup sensor the size of an iPhone. It’s these type of advances in technology, he believes, that will answer some basic questions that lend intrigue to the underwater giants — such as how much they eat, how deep they dive and how they communicate.

Pyenson was on the team that discovered a graveyard of whale family groups stranded over millions of years in the same spot in the Atacama Desert of Chile. It was unearthed in 2011 as the Pan-American highway was being constructed. The find highlights the advantage of technology in paleontology in the field.

The scale of the discovery at the site dubbed Cerro Ballena was so large — and the timeline for analysis so small — that the Smithsonian’s 3-D scanning team traveled to the site to capture the fossils using digital imagery. (See the 3-D Cerro Ballena fossils here.) The technology was used on the nation’s T. rex, which will be on display in the fossil hall.

With the deadline of the fossil hall’s opening next June looming large, the crunch is on to tell the story of more than 700 rare specimens. However, there could be some late additions from Pyenson’s lab.

“We’re still discovering more fossil whales. There’s one. It’s actually right on the floor over there,” Pyenson says, pointing to the corner of his office.

“That’s a new species of fossil baleen whale. It’s 32 million years old. We have a name. I can’t tell you it right now because it’s in review,” he said.