WASHINGTON — Fire and ambulance response times have improved in D.C., and officials detailed plans Wednesday to advance emergency medical service as well.

Since 2015, officials said, the city has bought or refurbished dozens of ambulances, fire engines and ladder trucks, hired more than a hundred firefighter medics and boosted training schedules.

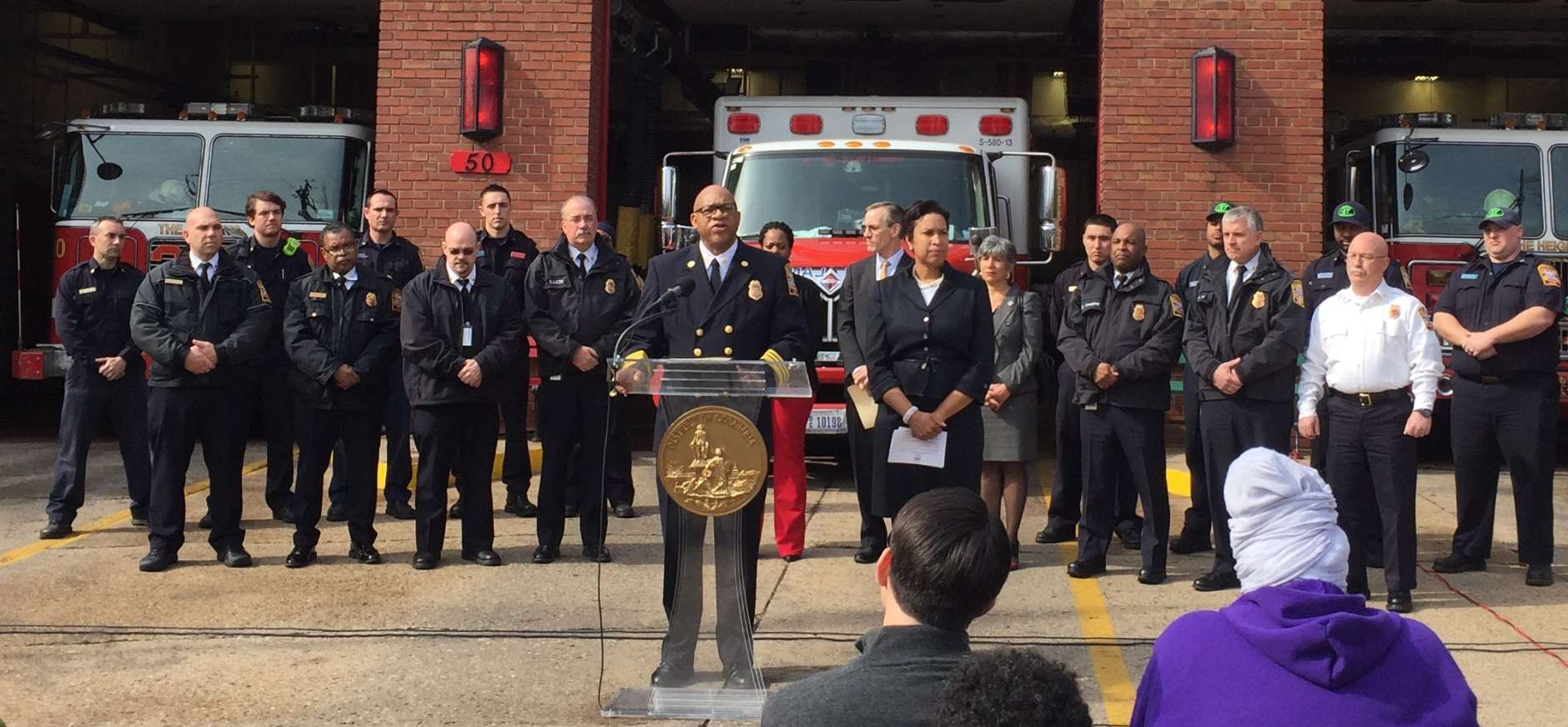

“We’ve seen an improvement of 41 seconds in our first unit on scene,” said Chief Gregory Dean of the D.C. Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department, in regards to fire engine and ladder truck responses.

“Our average ambulance response time has also improved, from 8 minutes and 7 seconds to 6 minutes and 30 seconds,” Dean said.

Calling the advances “incredible progress,” Mayor Muriel Bowser said that more than 500 city residents call 911 for help every day.

And some residents are helping, she said. Bowser credits free city CPR classes with a 20 percent increase in cases in which bystanders help someone in medical distress before professionals arrive.

In the coming weeks, Bowser will introduce legislation to the D.C. Council that would require insurance companies to cover ambulance expenses instead of passing any on to customers.

“We’re a city where we have almost 100 percent insurance coverage,” Bowser said, “so there’s really no reason why a D.C. resident should be getting a bill for an ambulance ride.”

Longer-term plans for improvement

D.C. may become the first jurisdiction in the region, and one of just a few nationwide, to create a “nurse triage” line that’s incorporated into the 911 system.

As part of the concept, 911 operators transfer calls of a less-serious nature to someone who evaluates the caller’s needs, then makes same-day appointments and arranges transportation to medical care.

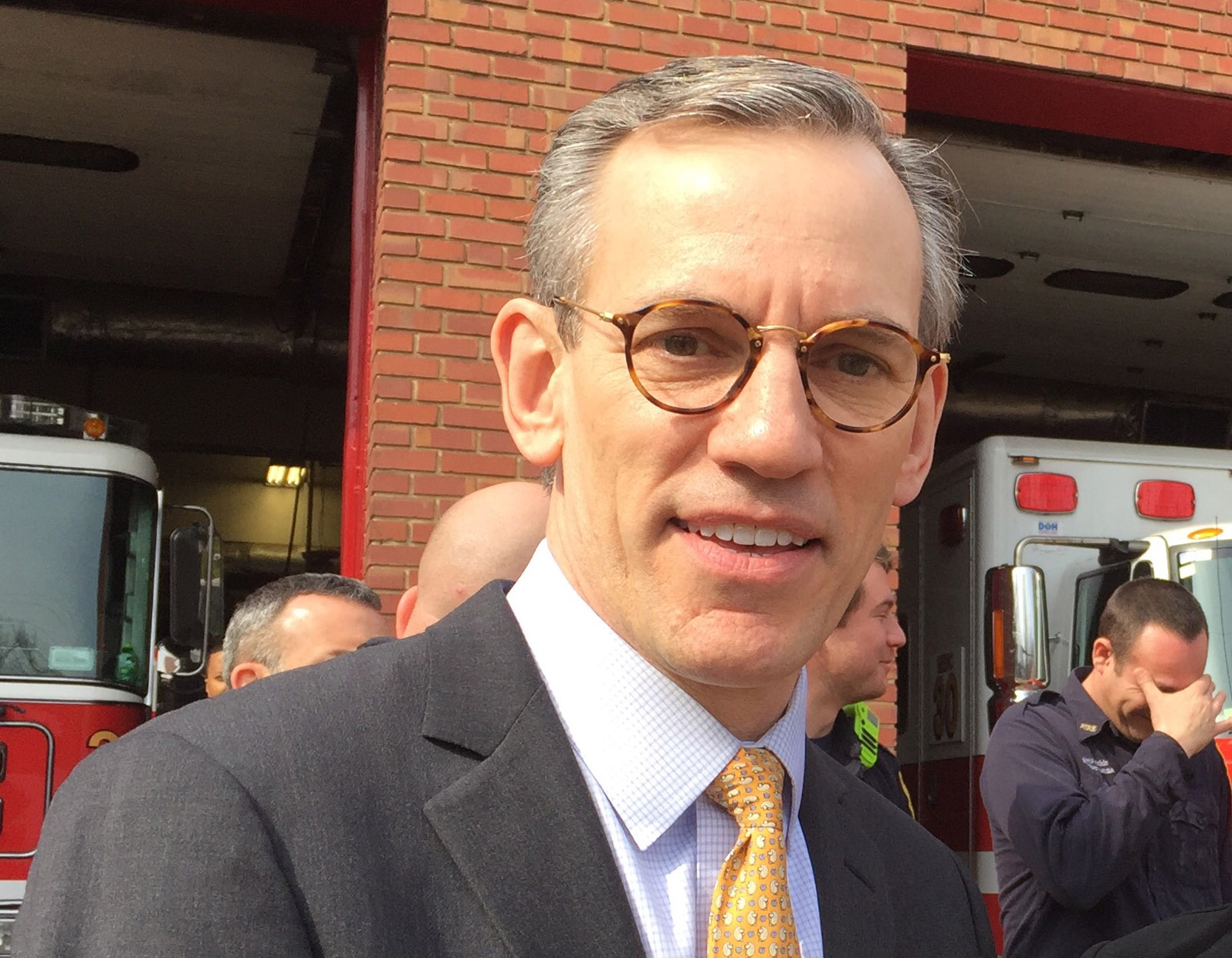

The nurse triage line concept was created in 2001 and is common in Europe, said Dr. Robert Holman, interim medical director for D.C. Fire and EMS. It currently is used in cities including Fort Worth, Texas, and Reno, Nevada.

“We’re groundbreaking,” Holman said. “It’s not that common.”

Nearly half the calls to 911 for help in D.C. in fiscal years 2015 and 2016 involved situations that were not considered an emergency or life-threatening.

“Rather than limb- or life-threatening medical illnesses, these are simple things like sore throats, toothaches, bladder infections and mosquito bites,” Holman said.

On Tuesday alone, for instance, D.C. Fire and EMS handled 519 calls, including 240 that were considered “critical.” Just under 200 (190) were classified as non-critical, the department said.

To examine that and related issues — and to make recommendations for improvement — Holman brought together community partners to create a group known as the Integrated Healthcare Collaborative last April. Establishing the triage nurse program was one of that group’s recommendations.

“We’re excited about this. We have a few hurdles, but we think we can launch this by the end of the calendar year,” Holman said.

Some of the hurdles include getting money allocated in the fiscal 2018 budget, finding a vendor to provide the service and ensuring that partner clinics have capacity for additional patients.