WASHINGTON — As a safety oversight commission for Metro marches closer to reality, the D.C. Council has made changes to authorizing legislation to make it easier for the public to also keep an eye on the transit agency’s safety record.

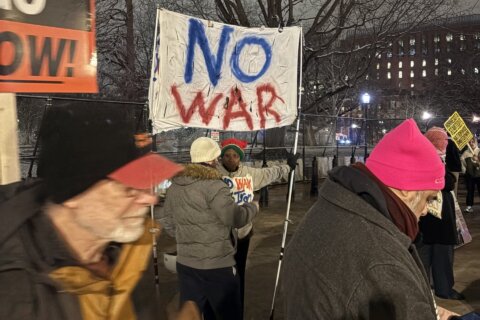

The D.C. Council held a public hearing on Tuesday about a bill that would establish the regional Metrorail Safety Commission, a federally-mandated agency that would be charged with inspecting and enforcing safety standards for Metro. Budget details and also possible commission appointments were also discussed.

The Council has revised the bill to increase transparency and provide public access to the commission’s work including access to meetings and the ability to request documents and records by requiring the commission to adhere to the federal public records law.

Originally, the draft legislation did not require the commission to be subject to state open records laws but would have allowed the commission to set its own policies using the federal law as a guide.

“You need the oversight commission to watch Metro and you need the public to be able to watch the oversight commission,” said Kevin Goldberg, president of the D.C. Open Government Coalition, who testified during the hearing. “I think there always needs to be somebody watching the watchman.”

Goldberg supports the changes, but suggested more revisions were needed to address the appeals process when requests for information would be denied.

Maryland, Virginia and D.C. must adopt identical legislation to create the commission.

The bill would empower the oversight commission to issue fines, direct Metro to prioritize spending on safety, restrict or suspend rail service to all or part of the system, direct Metro to suspend an employee if necessary, take legal action, and to compel Metro’s Office of the Inspector General to conduct audits.

A budget estimate

Leif Dormsjo, director of the District Department of Transportation, estimates the commission’s budget would be about $3 million to $6 million per year. The federal government would provide grant funding and D.C., Maryland and Virginia would contribute equally to cover the balance.

If D.C., Maryland and Virginia officials approve the commission, but later refuse to provide adequate funding, the commission would fail, he cautioned.

“Starving a safety oversight body of funding is normally not good politics,” Dormsjo said.

Tight timeline

The commission would replace the now-defunct Tri-State Oversight Committee, which had no enforcement power and was deemed ineffective following the deadly smoke incident at the L’Enfant Plaza station in January 2015. U.S. Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx gave the Federal Transit Administration direct oversight of Metro safety later that year.

Foxx has set a deadline of February 2017 for D.C., Maryland, and Virginia to form a safety watchdog agency with “teeth.” Officials rolled out the proposed framework for the new agency last spring.

The Council wants to approve the bill by the end of this year. But the February 2017 deadline might be very difficult for Virginia and Maryland to meet, because state lawmakers will only have a few weeks to push the legislation through their respective general assemblies.

“We need to make sure that the commission is adequately funded … so the budget cycles of all three jurisdictions need to take into account that this commission is going to have expenses and is going to need access to public funds,” said Dormsjo. “Hopefully the FTA will not withdraw their oversight role come February 2017 and leave the riders and agency in a lurch.”

He also said officials should begin looking for potential candidates to serve on the commission — a search that should be national in scope to find the most qualified experts.

“Oftentimes commissions of a regional nature like this focus on residency requirement or focus on membership or leadership within a particular organization. I think the focus here has been on the credentials of the people who would be serving,” Dormsjo said.

Each jurisdiction would appoint safety experts to the commission. But unlike the Metro board, the members cannot hold another public office to avoid a potential conflict of interest.

Dormsjo said the commission needs members with the unique experience managing transportation systems as large as Metro and who can handle money wisely.

“It’s probably the most fundamental thing that has gone wrong with WMATA over the last 10 years: Not understanding how to manage money to deliver safety enhancements. So having someone who understands the delivery of capital projects, whether we are talking about aviation or rail or transit, that type of background is completely relevant for what we are trying to accomplish here,” Dormsjo said.

D.C. Councilmember Jack Evans, who chairs the Metro board, was visibly frustrated with the lack of oversight at the public transit agency.

“Metro goes in to fix the system and make it safer and just doesn’t do it. Then they don’t want anybody to know they’re not doing it. Why don’t they just do it? It’s a rhetorical question. It just baffles me,” he said during the public hearing. “Is this where we are? Is this how ridiculous this whole thing has become? The answer is: It is.”

When Metro’s yearlong massive trackwork program ends next year, Evans said the safety improvements will be nowhere near complete.

“SafeTrack is an effort to fix the 15 worst parts of Metro. That doesn’t mean the rest of Metro is OK. It means the rest of Metro is still a wreck. When we finish the 15 parts, then the whole system will just be a wreck, not a total wreck. We have a lot of work to do on the entire system … I want to dispel the notion that us passing this legislation, that us finishing SafeTrack is going to be a fix for Metro,” Evans said.