I know several people who have had mild cases of COVID-19. When I tested positive for the coronavirus, that’s the kind of case I wanted. I didn’t get it.

It’s easy to think “It can’t possibly be me who will get this horrible version of COVID-19,” but I got it. I went on to make the kind of mistakes you read about, the ones that make you shake your head. Two months later, I’m still not back to 100%, but I’m back and happy about it.

If you get anything out of my story, I hope it’s to take any sign of COVID-19 — or any health problem — seriously, and get checked out.

‘Could this be a mistake?’

On New Year’s Day, I came down with some kind of virus — low-grade fever, aches, the works. Of course, I got tested for COVID-19 the next day, and it came back negative. I couldn’t work, of course, but I told News Director Darci Marchese that I felt OK and would surely beat whatever it was pretty quickly.

But I continued to feel worse.

On Jan. 9, I went to an urgent care center for another test. The rapid test was negative, but Monday, Jan. 11, the more-reliable PCR test came back positive. To this day, I have no idea how or where I got the virus. When the phone call came to say I had tested positive, my first response was “No. Could this be a mistake?” The answer, of course, was “No.”

When I called my doctor that day to tell him the news, he put me on the list for a monoclonal antibodies infusion, a treatment that’s used in the early stages of the disease. They called me on Wednesday to tell me that a spot had opened up for me. It was already too late.

To the hospital

They say COVID-19 causes “brain fog.” I don’t know whether that’s what I had, but during the two days I was home after my positive test — Jan. 11 and 12 — I ignored some pretty obvious warning signs that I was really sick.

I couldn’t carry a light blanket from my bed into the living room. I slept for 11 hours two nights in a row. I could barely breathe when I was lying down. My daughter had to pick up a prescription for me, because I couldn’t go more than a couple of steps from my apartment. None of this registered. I live alone, so no one was seeing this up close — and, of course, given the nature of the disease, no one was visiting for very long.

And I’m not the type to avoid medical care. You have to convince some people to go to a doctor, but that’s not me. I go to my regular checkups; I go to my ophthalmologist, my dentist, and I get medical attention if I need it. So, looking back, it was kind of odd that I was so resistant to getting care when I actually needed it more than ever.

On Tuesday, Jan. 12, I had perked myself up long enough for a quick teleconference with my doctor that day, but later that evening, I couldn’t hide it any longer. My daughter, who is a nurse, and my girlfriend were telling me to call 911; they were also talking to each other, and were headed over to convince me to make the call, until I told them both I was doing it. One of the doctors at the hospital told me I might not have made it through the night if I hadn’t.

Your blood oxygen level is supposed to be 94 or above. Anything below 90 and you’re in trouble. They put me on oxygen in the ambulance, and when I got to the emergency room, my level was still only in the 70s.

After an X-ray and a CT scan of my chest, they admitted me for treatment of COVID pneumonia and hypoxia (a lack of oxygen to the vital organs).

12 days

The stereotype about being in the hospital is that they never leave you alone: They wake you up every two hours to take your vitals or take your blood. But with COVID-19, it’s different. I wasn’t in the ICU or on a ventilator, but I was in isolation — isolation from other patients and from the staff. I was in great hands, but the staff came in only when necessary and did as much as possible in each visit. That loneliness is something to deal with.

I was in the hospital for 12 days, and when you can’t even walk in the hallway, it’s even more boring than the usual stay: From the bed to the chair, pacing the floor, and that’s about it. I watched a lot of news on the TV — there was plenty of news going on at the time — and without a radio audience to speak to, I gave a lot of commentary to no one.

I actually wondered at one point, a few days in: Are they paying enough attention to me? Later on, I found out what it’s like when they pay attention to you, and I didn’t complain about isolation anymore.

On the fourth day, I felt like I wasn’t sick at all. They took me off the oxygen and checked my blood oxygen level. It was fine. I got cocky; I thought I had beaten it in four days.

Nope. On Day 5, I developed atrial fibrillation — an intermittent, really rapid heartbeat. They told me that’s not unusual, that sometimes it’s just from the shock of your body dealing with the virus, and it could go away and never come back again. And gratefully, that’s exactly what happened. But I found out what it’s like to be the one they pay attention to, and I was fine with being left alone after that.

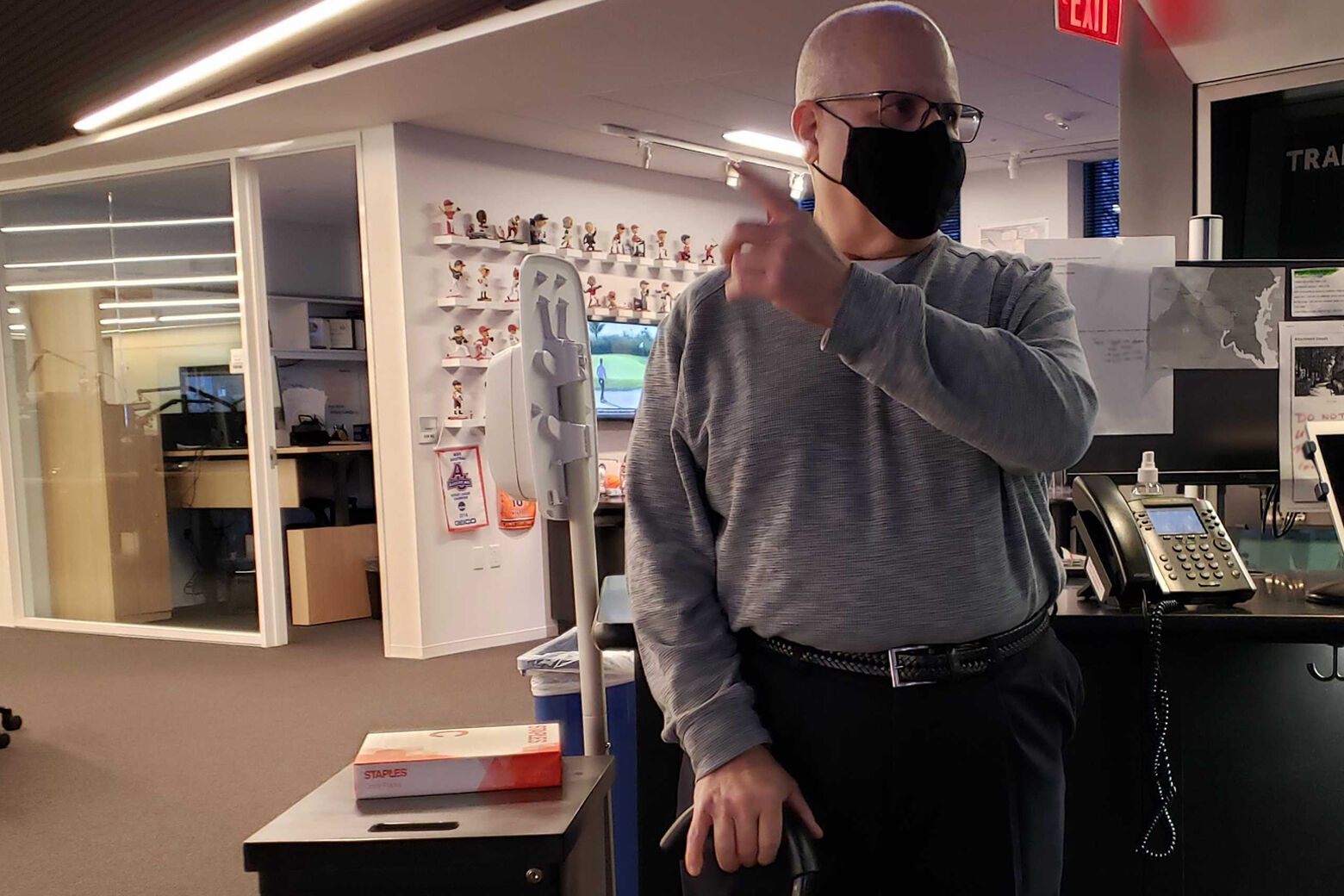

Back to work

As much as I feel like I have been through hell, a lot of people were much worse off than me with this thing, so I have perspective on where I fell on the scale.

People say COVID-19 made some of their preexisting conditions worse. For me, the hip I had surgery on three years ago seems to have been targeted as a weak spot; there isn’t any new damage, but somehow it feels like I’m recovering all over again.

I’m off oxygen; I can take deep breaths, and I can talk for a fair amount of time. But I still cough sometimes, and I have no stamina. I started working half-days last week; when I went home the first day, I slept in the chair for two hours.

My first two days back, I recorded stories for the air, but since my voice starts to sound tired pretty quickly, I had to rerecord them the next morning. Nobody asked me to, but when I listened back, the sound of my voice bothered me.

Still, I am so happy to be back. And I can’t wait till I have my stamina again, and I’m back on the air weekday mornings.

I want to thank everyone in and out of the hospital who looked out for me and took care of me. And I can’t emphasize enough: Take everything seriously. If you have any concerns, get tested and find out. If you even think you need medical care, go seek it out. The worst that can happen is they’ll tell you, “you’re OK.”

I gave COVID-19 too much of a head start, and I almost paid for it with my life.