WASHINGTON — Each month the Bureau of Labor Statistics releases a detailed report on inflation, compiling price information for thousands of goods and services with a goal of measuring the change in the cost of living for an average person.

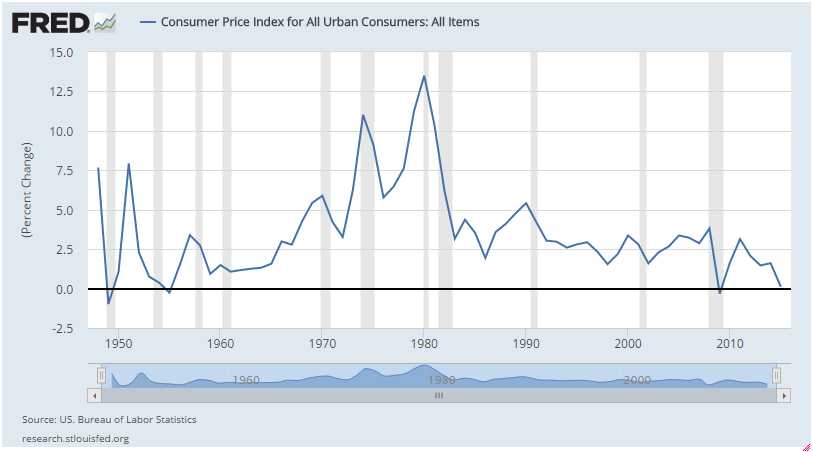

If these prices are going up, we have inflation. If they’re going down, we have deflation. People inside and outside the financial industry have been predicting higher inflation for years, yet inflation has remained low.

Here’s the chart of inflation through the past few decades. Higher inflation predictions have certainly not come to fruition:

A monetary phenomenon

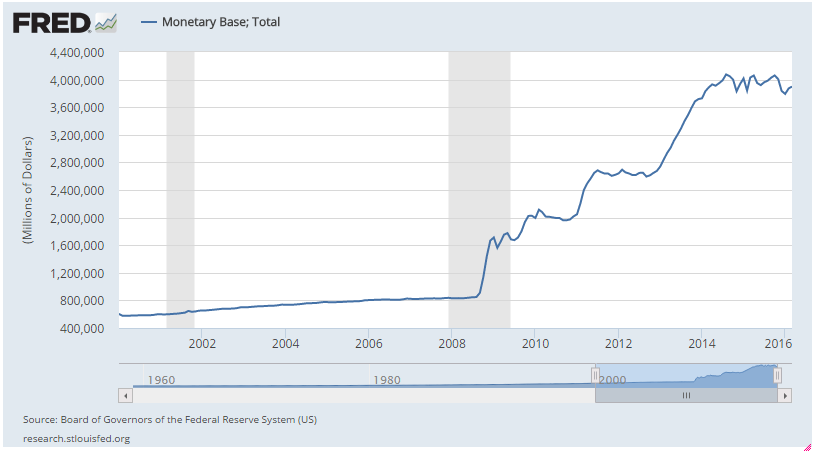

It’s old news that the Federal Reserve has put a ton of money into the financial system during and since the financial crisis.

Just to see how much extra money the Fed has pumped into the system, below is a graph of the total US monetary base:

Why should this cause inflation? As a simple example, imagine you’re playing Monopoly — the classic board game in which every player is given $1,500 and can buy and sell pieces of “property” with the goal of becoming the richest player in the game. When properties are auctioned, their prices depend on how much each player is willing to spend.

Now imagine each player is given $15,000 instead of $1,500 at the beginning of the game. Each player is operating on a significantly higher budget and will likely spend more on each property. This is a bit of monetary policy in action: The higher the money supply (the amount of money in the game), the higher the prices, as more money “chases” the same number of goods.

Given the massive amount of stimulus undertaken by central bankers, why haven’t we seen excessive amounts of inflation?

Velocity

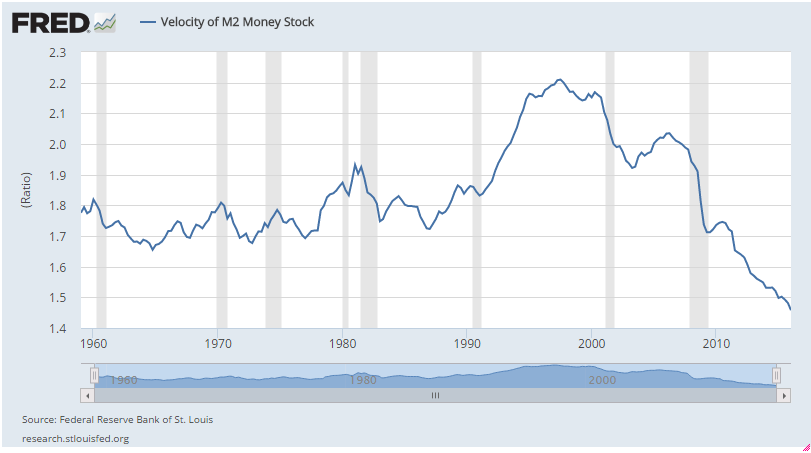

Central bankers cannot control spending, lending or the flow of dollars through the economy. There can be plenty of money out there (in consumers’ hands or in bank reserves), but if money isn’t changing hands, there won’t be inflation.

Back to our board game analogy: Even if there is more money in the Monopoly game, the prices of each property won’t rise unless people collect money from the bank, bid up property prices and spend it.

The graph above shows the “velocity” of money, or how frequently money changes hands. This has been in a steady decline in recent years and seems to be the main reason inflation isn’t picking up. In fact, it’s hit a 50-plus year low. I see two principal reasons for this:

- Increased savings: Even as disposable income has risen since the recession, consumer debt has gone down. Rather than spending that disposable income, consumers are saving their money. Lower interest rates have also allowed people to refinance their mortgages and pay down debt.

- Low borrowing: The stimulus undertaken by the Federal Reserve has created a lot of excess reserves within the banking system. However, much of that money isn’t making its way into the real economy because consumers are not borrowing to the same degree that money is created. Despite the fact that interest rates are low, people are understandably wary of excessive credit after the collapse of the housing bubble.

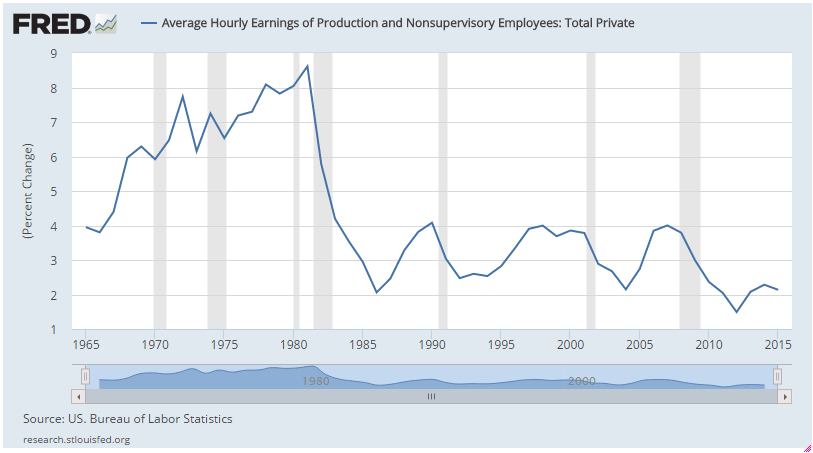

Wages keep up?

People will not (or cannot) pay higher prices if they can’t afford them. Although wages have risen over this time period, there really hasn’t been much wage growth after adjusting for price inflation, especially for the middle class. Without wage growth, people can’t spend more without borrowing.

The Fed is hoping that inflation ticks up to around 2 percent, not because a rise in prices is inherently good, but because it could be a symptom of a stronger underlying economy. When that uptick occurs will almost certainly be dependent on two things — the velocity of money and wage growth.