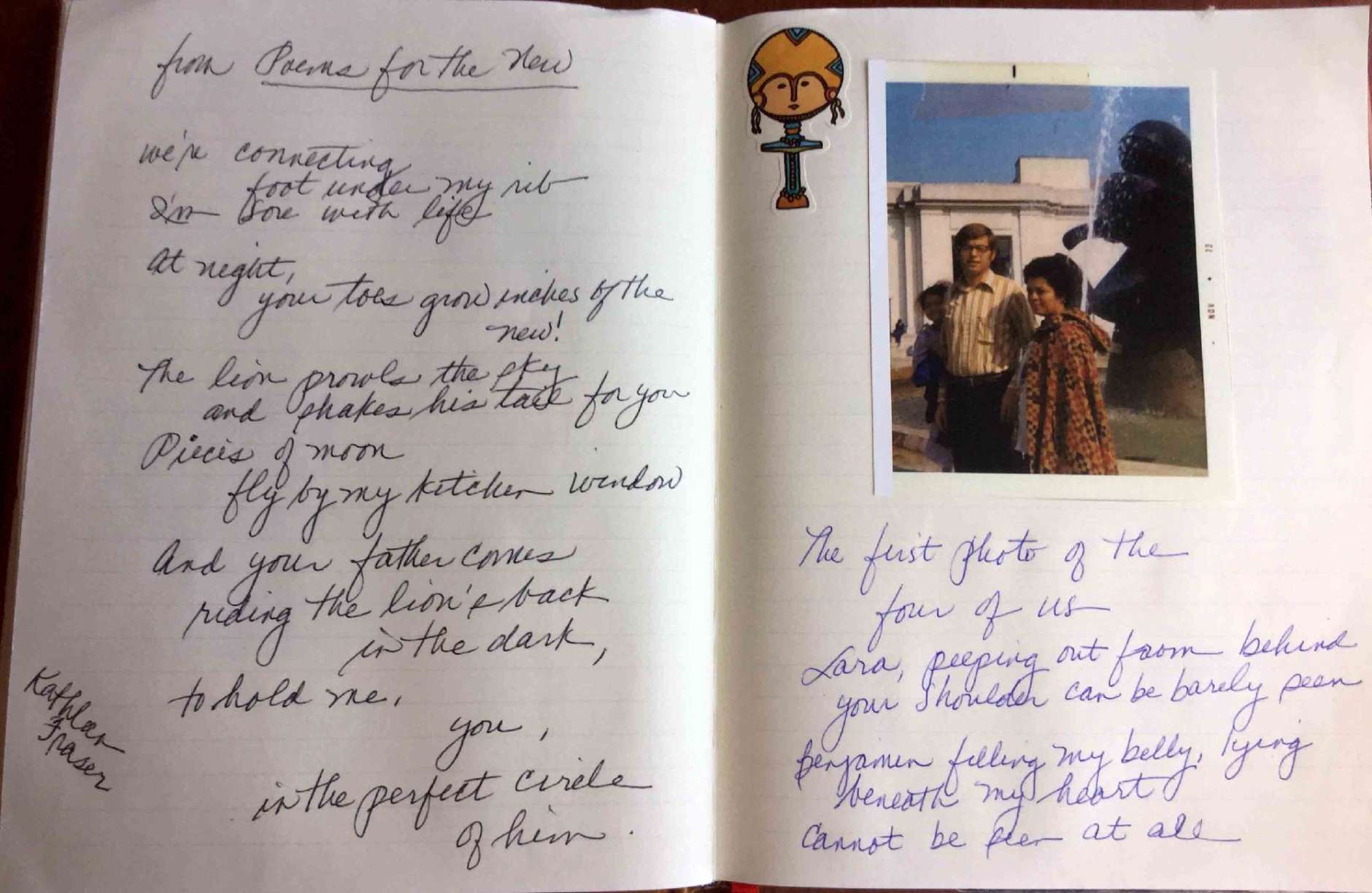

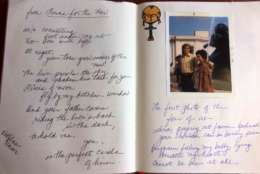

WASHINGTON — When you’re in love, you find ways to overcome obstacles. And when one of you is white and the other is black, and it’s Baltimore in the mid-60s, you get creative.

“We would identify two empty seats,” said Ann Todd Jealous about movie theater dates with her future husband Fred.

“He would walk down one aisle, I would walk down the other, and we’d meet together. But we would not look like we were sitting together.”

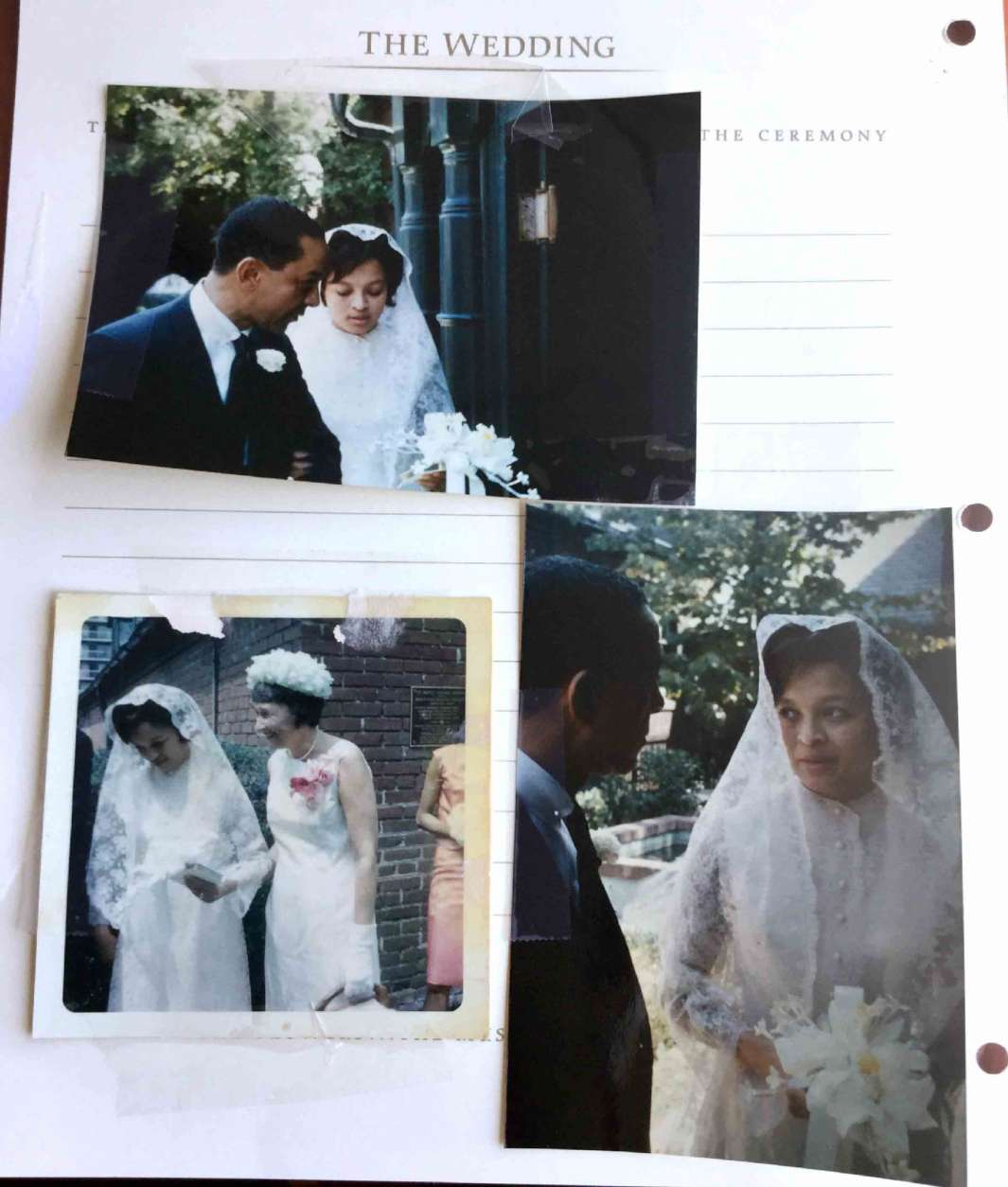

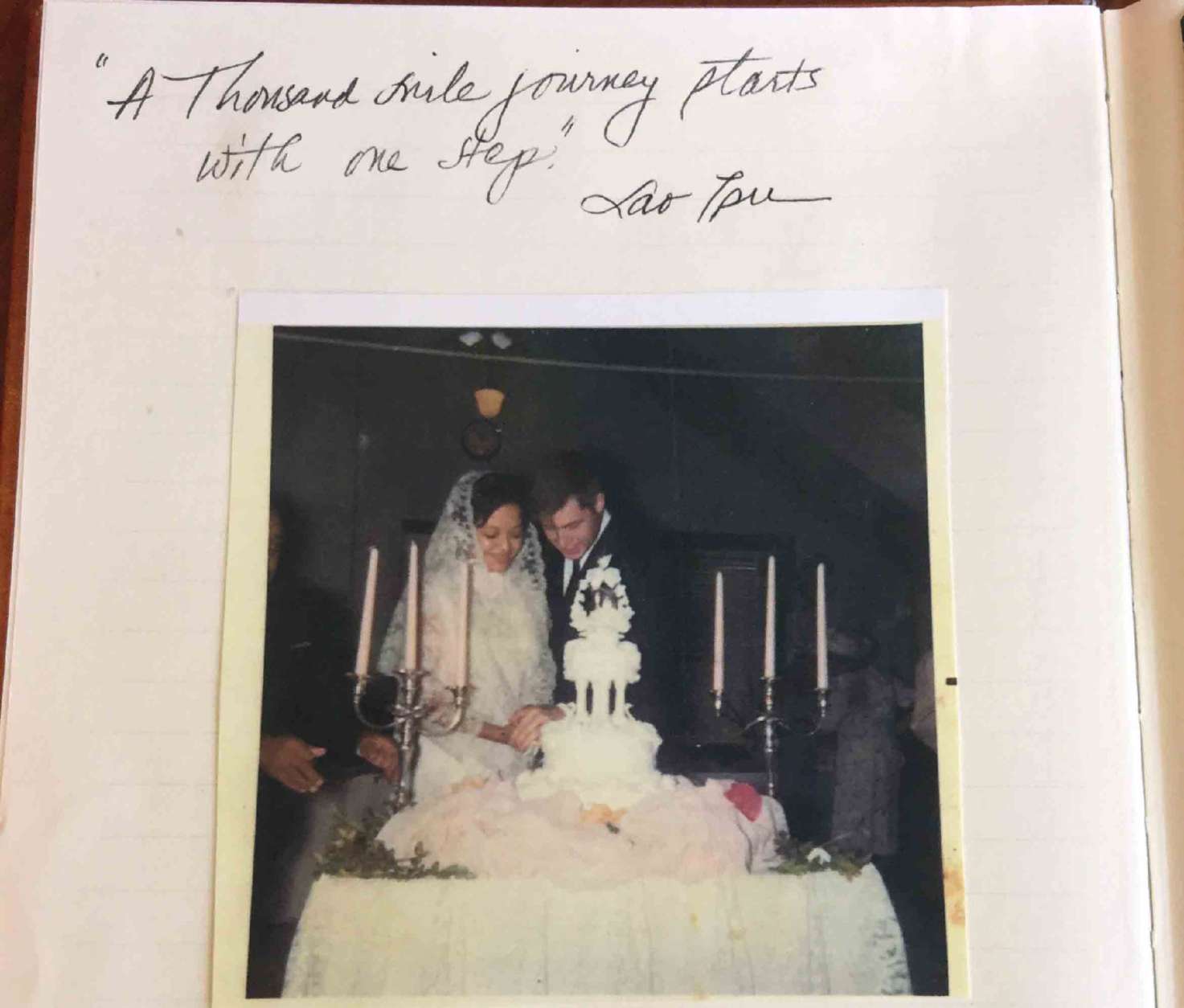

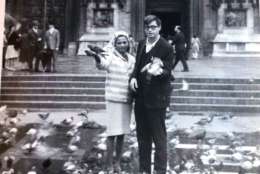

But that was an easier fix than what was to come, when Fred asked Ann to marry him. In 1966 it was illegal in Maryland for them to marry.

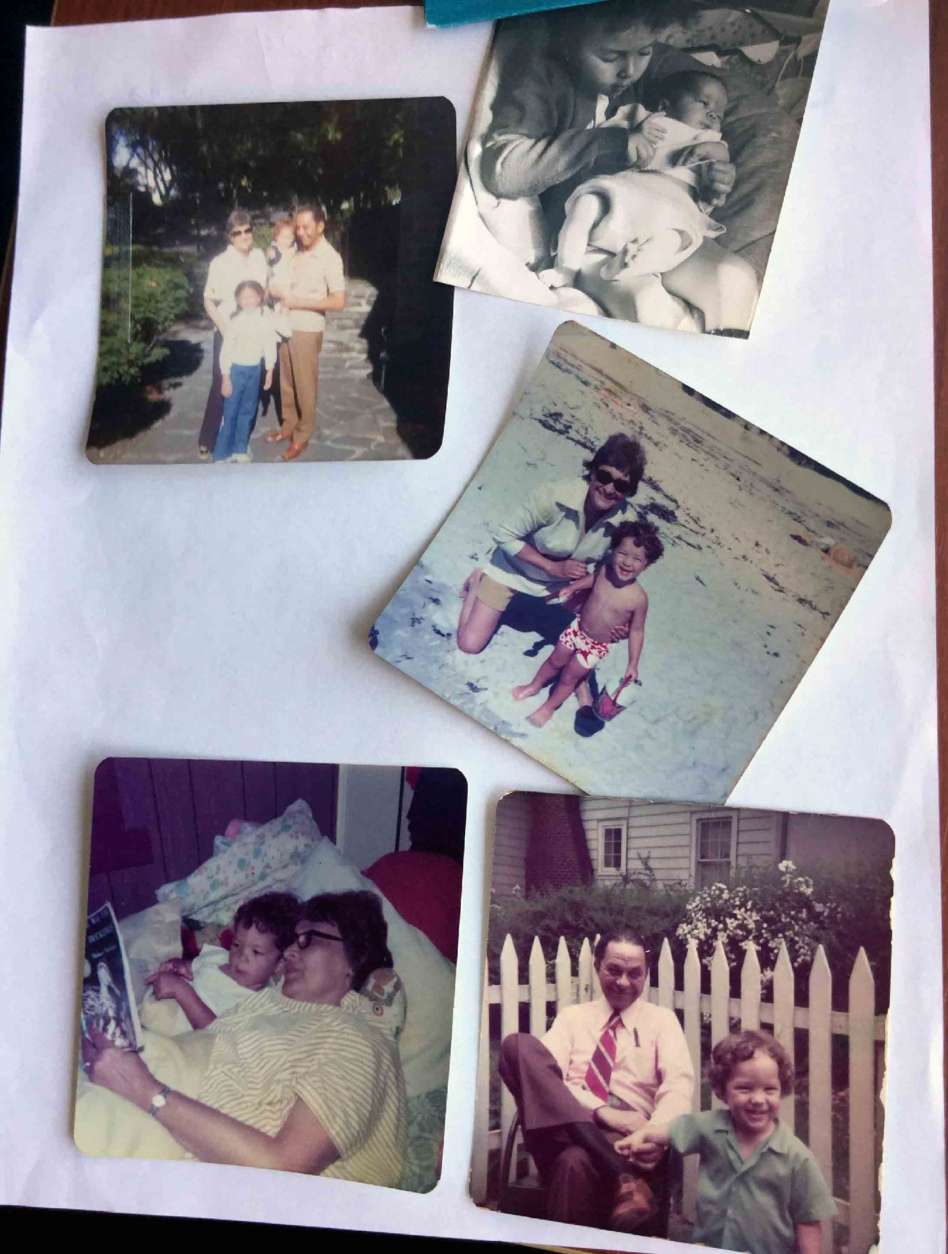

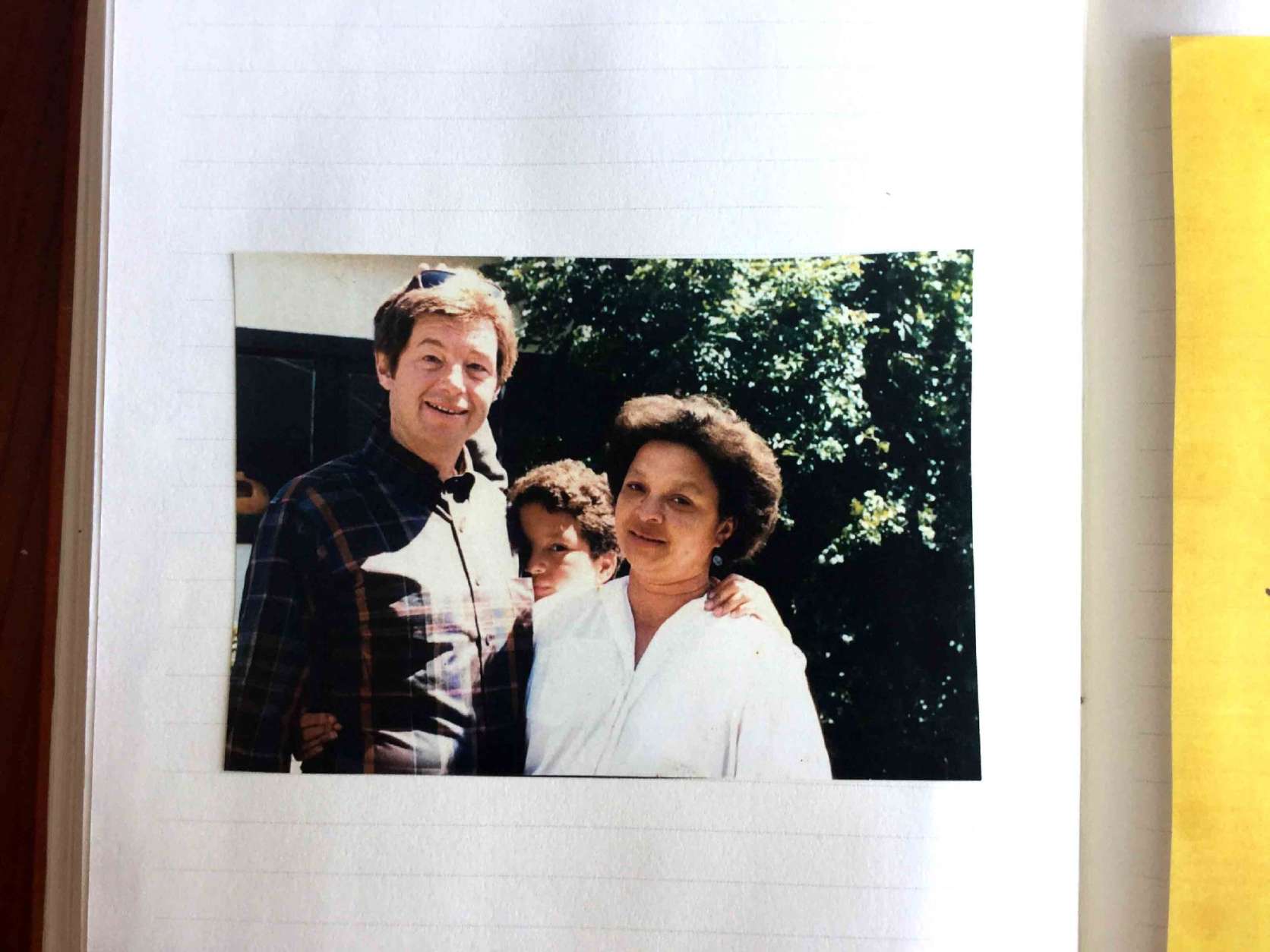

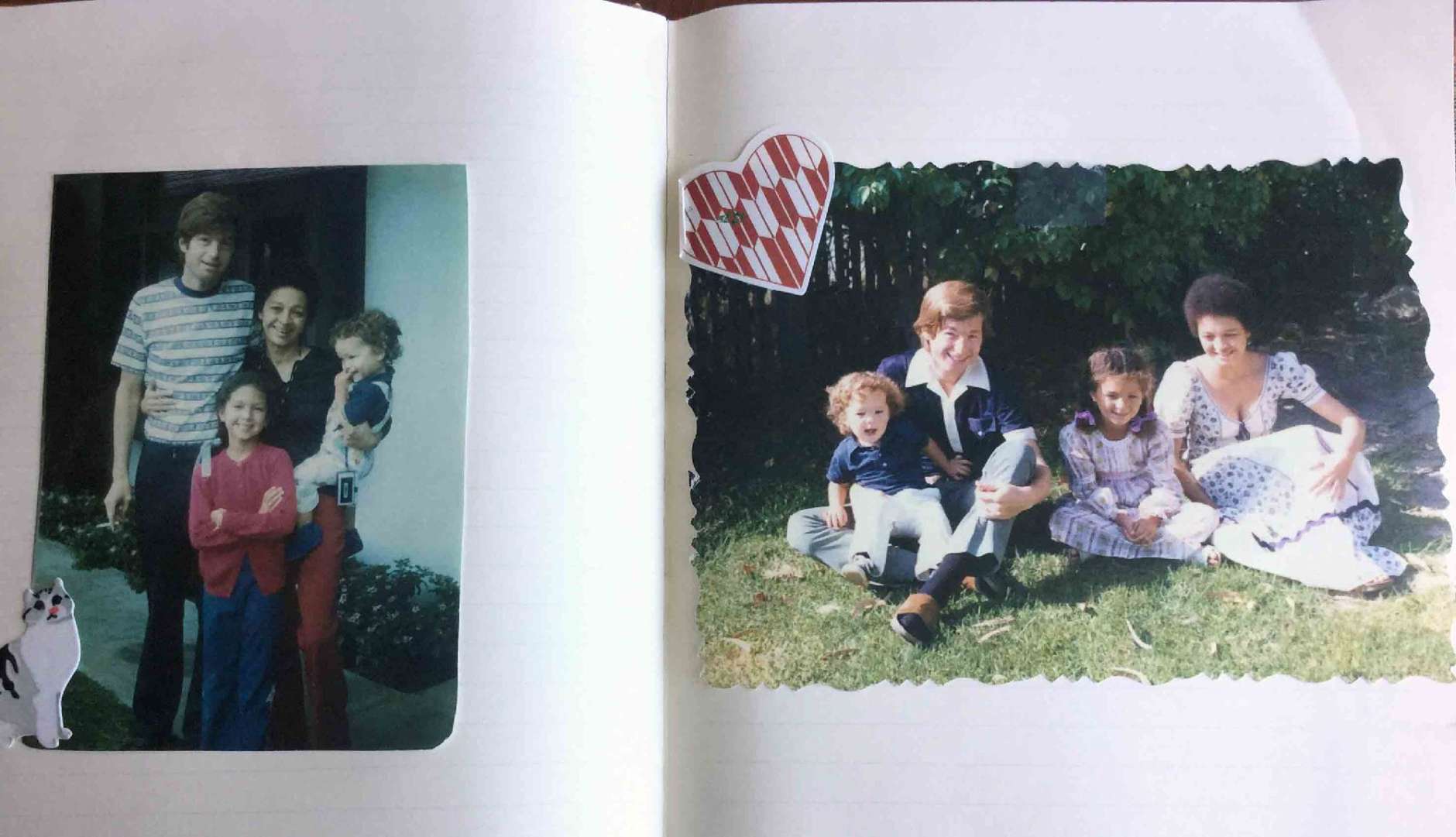

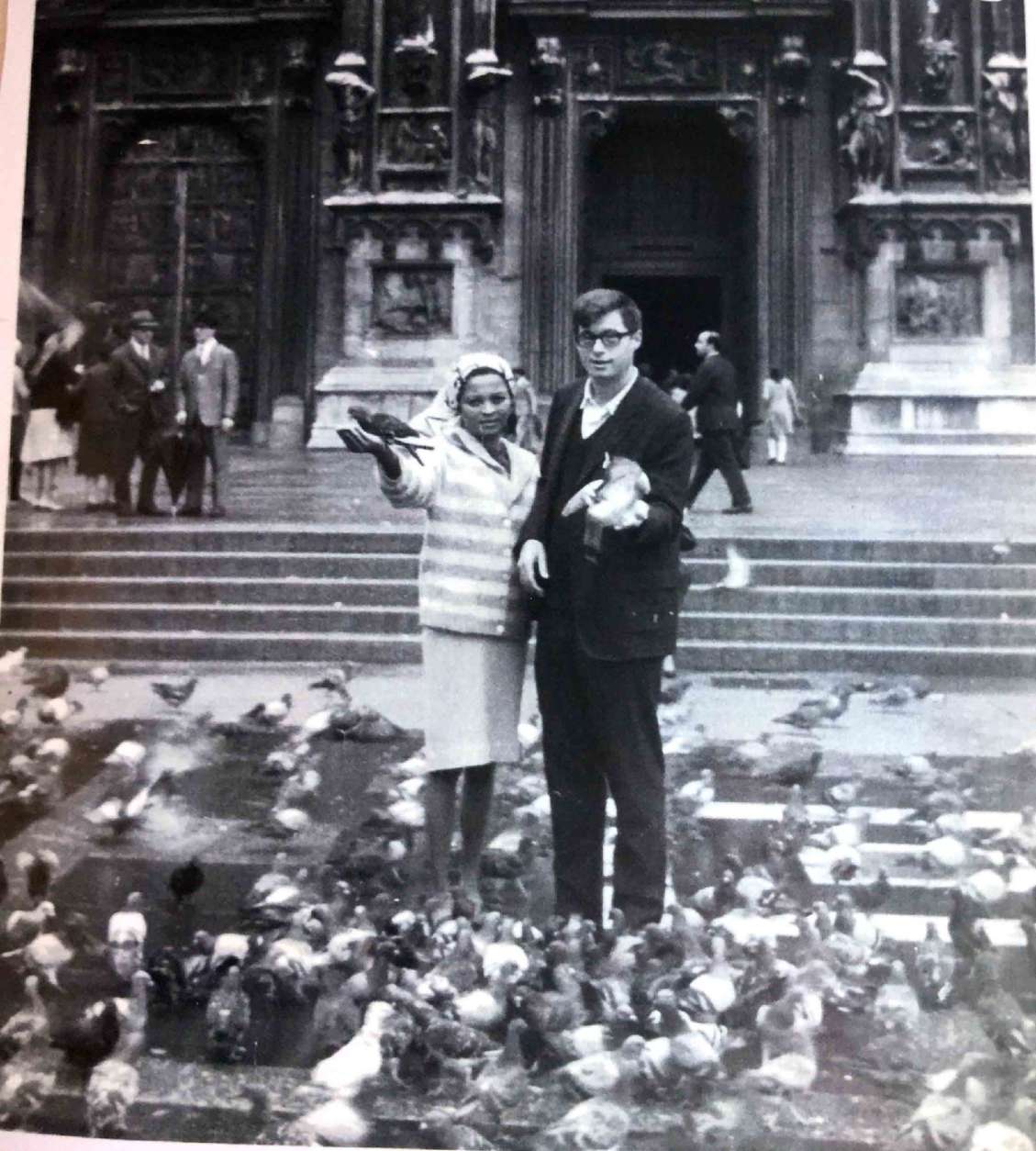

Fred, a white man from Portland, Maine, and Ann, an African-American Baltimore native, met during inner-city teaching assignments while in graduate school. By then, both were veteran human rights activists — she in the Peace Corps, he teaching in Turkey.

“We went out together a week in June,” said Fred. “And that was it,” added Ann. “He then he proposed — three times.”

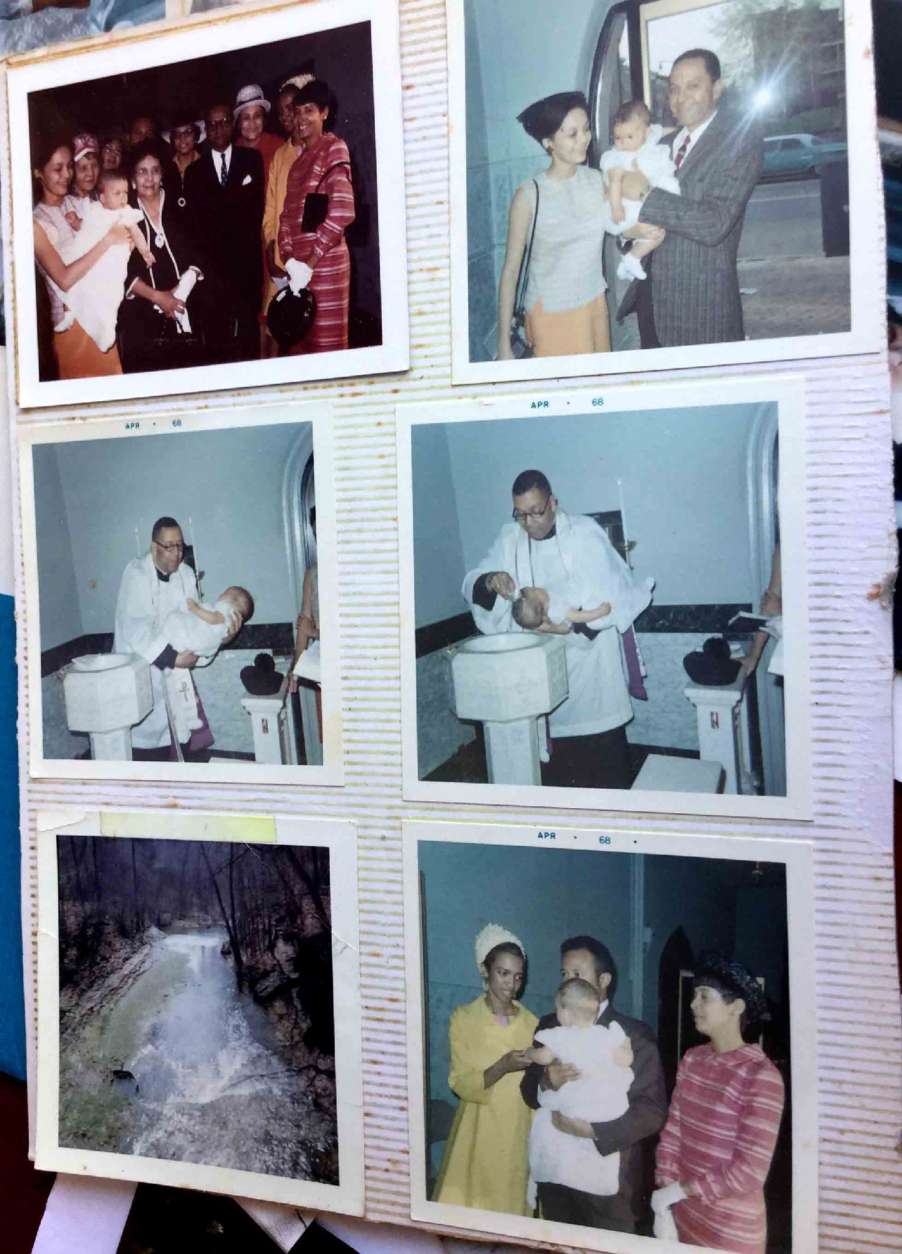

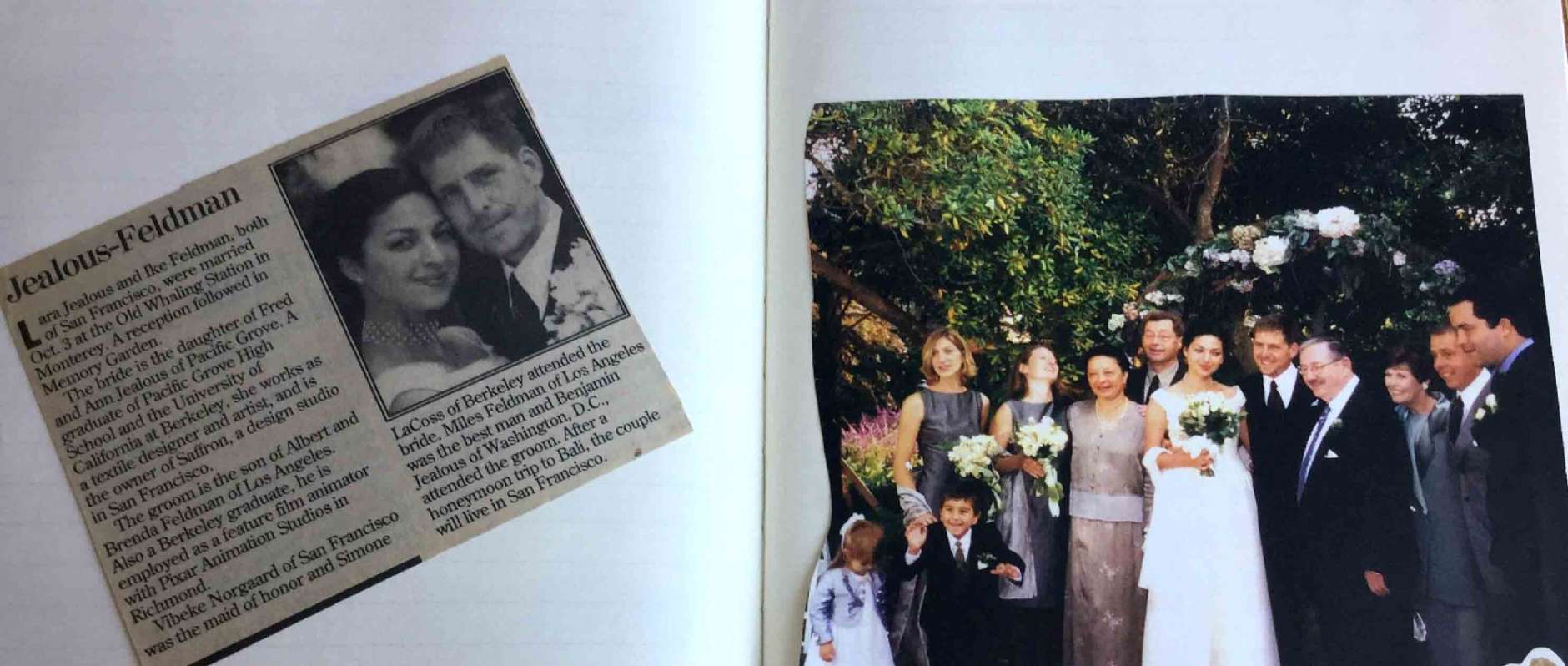

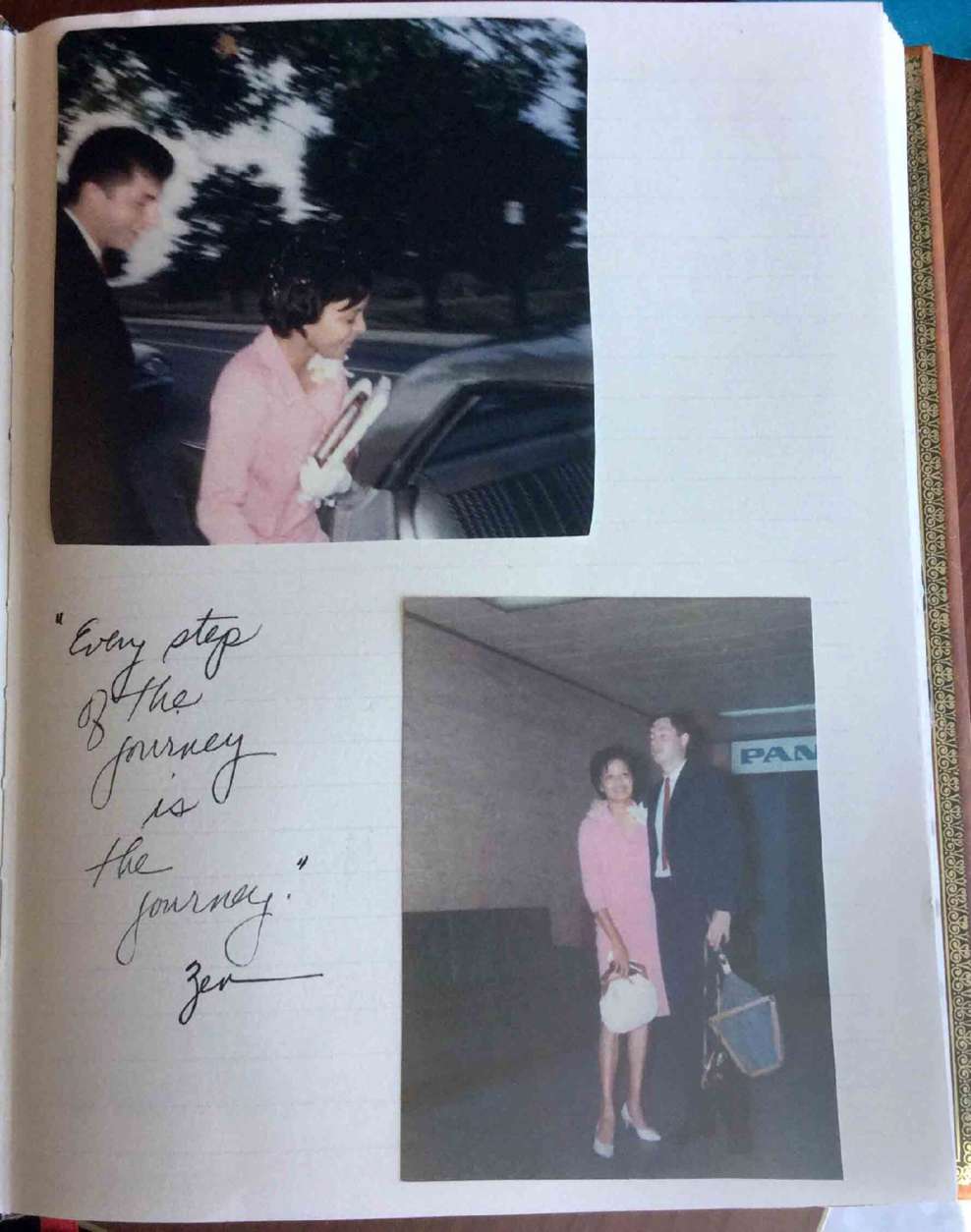

The Jealous’ whirlwind romance began when they met in January 1966. It led to their marriage in August of that year and continues today, nearly 51 years later.

“It didn’t occur to him that (there would be) any difficulty,” said Ann. “But it occurred to me. I grew up in total segregation. So it didn’t even occur to me to think of him as a potential mate.”

That first proposal came with a swift response, said Ann.

“I thought, ‘My God, this is crazy. This is against the law’.”

And that was more than just theory to Ann, who was among the first black students to attend Western High School in Baltimore when she was 14.

“People picketing to get me out, and people inside wanting me not to be there,” she said.

She coped by emotionally detaching herself from the moment. And she says that same detachment cropped up when she realized that she and Fred couldn’t get married in Maryland.

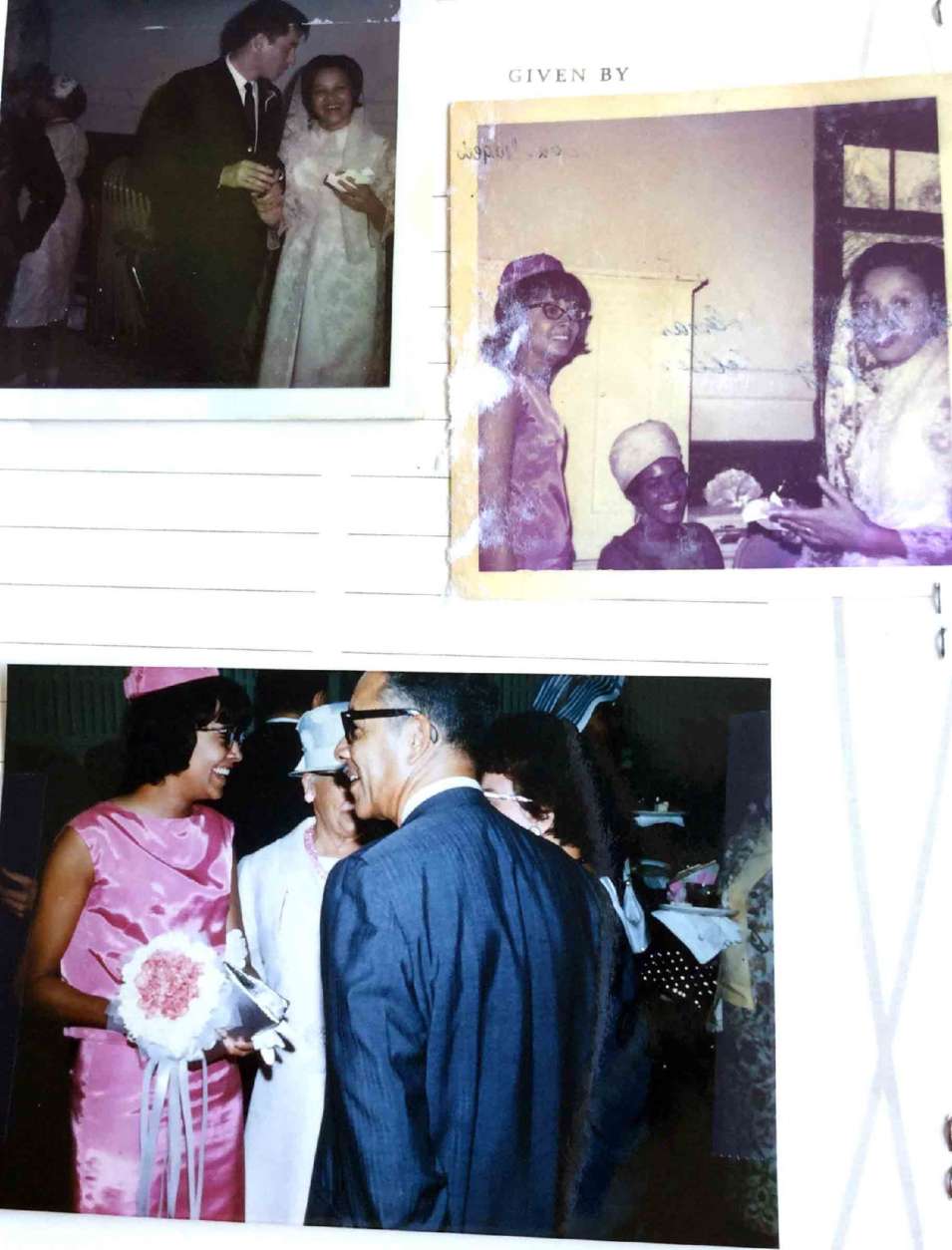

“Where can we get married? We can get married in Washington, D.C. OK. You go do that. And you ask the 100 guests who are coming to the wedding to drive all the way to Washington, and then to drive back to Maryland to have a reception at your mother’s home.”

“I could not let myself feel the feelings about it, or I would have been paralyzed,” she said.

A year later, the whole thing was made moot by the Supreme Court of the United States ruling in Loving vs. Virginia. The court struck down the anti-miscegenation laws in effect in Virginia, Maryland and 14 other states.

“It was huge for me,” said Ann. “All of a sudden, we were human beings. We’re not a caste.”

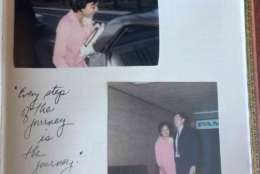

Since then, Ann and Fred Jealous have been at the tip of the spear in the battle for human rights from their home in Monterey County, California.

“I saw the dark, ugly, violent underpinning of white supremacy,” said Fred. In 1987 he founded Breakthrough, which calls itself “a community of men dedicated to making real change in the quality of men’s lives.”

Ann is a psychotherapist who’s used her experience in a biracial marriage to help others. She is the co-author of “Combined Destinies: Whites Sharing Grief about Racism.”

Their son is Ben Jealous, former President and CEO of the NAACP. He recently announced his intent to run for governor of Maryland.

While the Jealous family’s legacy is long and solid, Ann Jealous said it all goes back to Loving vs. Virginia.

“If that law had not been changed, we would not be anywhere near where we are now.”