BALTIMORE, Md. — The events following the arrest and death of Freddie Gray put the spotlight on strained relationships between the City of Baltimore and some of its residents.

One year later, the Baltimore Police Department has made changes to how it operates and has taken steps to better connect with the people it serves.

“When the nation will one day look back at 2015, that will be the year that policing in America changed,” said Baltimore Police Commissioner Kevin Davis.

Davis took control of the police department last year, after Commissioner Anthony Batts was let go by Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake.

Davis said incidents involving police in Baltimore, Ferguson and New York City showed that zero-tolerance policing, which became popular as a tactic in the war on drugs in the 1990s, no longer works.

“A lot of those zero-tolerance policing strategies really created a gap between police officers and the community,” Davis said.

The commissioner said police officers will always be responsible for going after people who commit crimes, but over the last year there have been fewer discretionary arrests in the city for offenses such as loitering, trespassing and disorderly conduct — the sort of encounters with residents that Davis believes have left a bad taste in people’s mouths.

Davis wants to see his officers build relationships within the communities they are sworn to protect. To encourage a closer bond between officers and residents, Davis is requiring officers to attend interpersonal communication training courses. Also, all new recruits to the force will be placed on foot patrols for their first 90 days, so they can interact with residents in non-crisis situations.

The department is also getting officers more involved with community outreach programs such as Outward Bound, which gives kids in the city a chance to spend a day with a police officer. Davis said the department is also doing more to recognize officers who go above and beyond the call of duty to help people in the community.

In May, the police department will receive the first batch of 500 body cameras, to be worn by patrol officers.

“The community loves them; the cops love them. It adds to the civility that is so very necessary in our interactions with one another,” Davis said.

The spinal injury that took Gray’s life happened in the back of a police transport van. Davis said inspections have been put in place to make sure officers are following proper protocol. The department is getting new vans equipped with video cameras that will film all prisoner transports.

“The vast, vast majority of police officers come to work every day and consistently do the right thing,” Davis said.

As he looks forward, the police commissioner doesn’t believe there will be another night of unrest like the one seen last year.

“There is a collective resolve from everyone in Baltimore that I’ve interacted with to ensure that what happened last April and May doesn’t happen again,” Davis said.

Connecting with kids

The streets of West Baltimore remain dangerous, and for many of the children who live there, witnessing violent crimes, and coping with the aftermath, is a part of everyday life.

“It’s a community that’s numb to death, homicide and violence,” said Erica Alston, with the Penn North Foundation.

After the unrest, Alston wanted to help the community recover by creating a safe place for the neighborhood’s children to gather.

“There were kids playing in the middle of the street in between those teddy bear shrines and yellow crime tape,” Alston said.

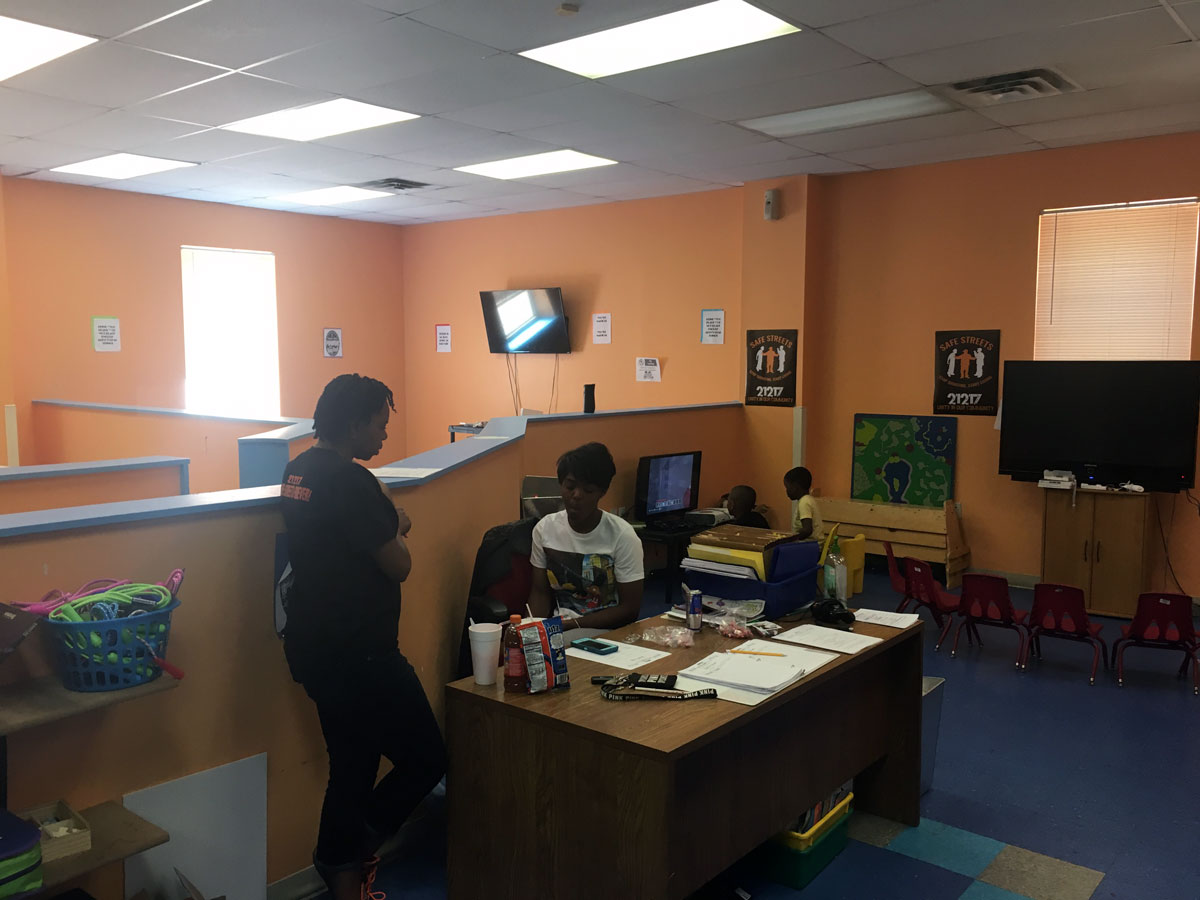

With the help of news media and social media, she was able to raise $80,000 in donations to open the Kids Safe Zone a month after the riots. Children ages 5 to 17 come to the Kids Safe Zone to get help with homework, use computers, play games and socialize.

“While other people were planning and yelling through bullhorns on what they thought the community needed, we did it,” Alston said.

The Kids Safe Zone started in a vacant laundromat, but now sits in an 8,000-square-foot facility not far from what was considered the epicenter for the unrest last year — West North and Pennsylvania avenues.

It isn’t out of the ordinary to see police officers in the facility playing with the kids.

Major Sheree Briscoe, commander of the western district of the Baltimore Police Department, said positive interactions between the kids and officers are important.

“My officers leave [Kids Safe Zone] feeling excited, getting reinvigorated about the task at hand and, more importantly, reinvigorated about community outreach,” Briscoe said.

Melanie Hall’s 6-year-old son enjoys coming to the center. She said she hopes having a positive place for him to spend time will keep him away from violence and drugs as he gets older.

Parents are also reaping the benefits of the Kids Safe Zone. It offers services to help them avoid eviction, keep the power on in their homes and even find work.

Alston tells every child who comes through the doors that they will graduate high school and that she plans to see them at their college graduations.

More than a year ago, Alston said, she would never have imagined that she would be working with a hundred school children each day. Now, she says, this center and the children are the things that wake her up in the morning.

“They’re in here because they need to be in here, and if we weren’t [here] they would be outside on the street and the streets here are not a good place,” Alston said.

You can donate to the Kids Safe Zone by visiting their website.