Anne Arundel County police made an announcement Wednesday morning that provided them with a lead after 34 years, and a sense of relief to a family after nearly 60.

A body found on April 23, 1985, was that of Roger Hearne Kelso, a young man who was born in 1943, lived on Whip Lane in Glen Burnie, Maryland, and had last been heard from in 1962, police announced at a news conference.

“I’m going to be leaving for a while,” police spokeswoman Jacklyn Davis characterized Kelso’s last remarks to his family. “Everything’s good.”

His body was found in a trash can that was dug up 23 years later on the construction site of what is now the Marley Station Mall, on Ritchie Highway, Smith said. He had seven coins in his pockets; the latest was dated 1963. But police couldn’t identify him with the tools they had at the time.

His body was taken to the medical examiner, who said he died of upper-body trauma, Smith said, adding that police couldn’t release any other details yet.

Police used all the tools at their disposal — dental records, sketches and more — with no luck. Last year, Detective Regina Collier contacted Parabon NanoLabs, a company that does various types of genetic testing and had previously generated a picture of what the victim probably looked like, which didn’t develop any leads.

Collier asked them whether they could perform what’s called “genetic genealogy” on the remains. They did. They confirmed on April 4 that the body was that of Kelso. At that point, authorities fanned out across the country, contacting Kelso’s relatives in Arizona, Washington state, Oregon, West Virginia and Maryland, leading up to Wednesday’s announcement.

“This new technology has allowed us to give us our victim a name after almost six decades,” Davis said. “It also let the family know where he was and what happened to him. And we’re also going to be able to return him to his family so they can give him the proper burial he has deserved for six decades.”

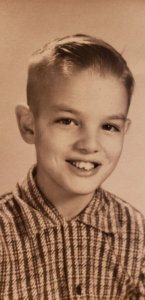

She said they’re releasing photos and information about Kelso, and asked anyone who knew him to come forward.

He graduated from Glen Burnie High School in 1961, and was president of the art club at some point. “Go back to your yearbooks; start wracking your memory,” Davis added. “Any information you can give us on Roger is going to help us.”

Anyone with any more information can call the police’s Cold Case Unit at (410) 222-4731, or the tip line at (410) 222-4700.

‘We fight for you’

Anne Arundel County Executive Steuart Pittman asked for a moment of silence in honor of Kelso, and then called the county police “the best police department in the country.”

Three of Kelso’s sisters were there, along with their children and grandchildren.

“I can’t imagine what it’s like to lose somebody and not know what happened,” Pittman said. “I hope we can take this to the next level and find the perpetrator as well.”

Police Chief Timothy Altomare said the case was an example of the department’s resolve — and of the helpfulness of new technology.

He pointed out that John Jaschik, the first detective to take the lead when the body was discovered in 1985, had been retired for more than 20 years, but came to the announcement. “He’s here today because he still cares,” Altomare said.

“I’m happy we could bring some answers” to the family, the chief said, adding, “We’ve got a lot of folks we still have to bring justice to in this county. … There are some folks here who are young enough, I guess, that they don’t remember this, but your suffering matters to us.”

Altomare said, “If you’re a member of the human race, we care about you. We fight for you. And the detectives of this department will never stop working to bring answers and justice to the families of the victims of violence.”

Referring to the new technology, he added, “Sometimes, we’ve got to take a breath and regroup, and do things a different way.”

He said police were offering a $10,000 reward for information that leads to an arrest on any open homicide, including this one: “Human beings matter, and we’re going to put our money where our mouth is.”

Altomare also stumped for the use of the technology, which has been criticized over privacy concerns, especially after it was used to catch a suspect in the Golden State killer case last year in part by matching the killer’s DNA with that of relatives who had submitted samples to a genealogy database. Reading a letter from a relative of Kelso’s, Altomare described the technology as “extremely important to policing.”

In a statement released by police, Parabon said they only use publicly available genetic genealogy databases, and that they “believe that participants are now aware that these databases could be used for law enforcement purposes.”

‘You wish you could have done more’

Wednesday’s announcement was a satisfying one to Jaschik, the former lead detective, and Mary Ellen Huffman, one of Kelso’s nine brothers and sisters.

Jaschik remembered getting the call to go to the construction site in 1985: “We had no idea what we would be up against.”

The nature of a construction site meant that everything had been away and there were no witnesses, which made it virtually impossible to identify the decades-old remains.

“It was the worst crime scene I’ve seen, as far as evidence goes,” Jaschik said. “Because there was none. There was just dirt and brick, and you couldn’t tell one thing from another. … There was just nothing there. It had all been destroyed by the bulldozers.”

The area was Jaschik’s old patrol area when he was a uniformed officer, he remembered, “But I never came across [Kelso’s] name. … It’s just one of those things you wish you could have done more.”

Jaschik came from Delaware for the announcement, and said it was satisfying to know that an identification had been made.

“I’m glad that they got this done. Because this was a pretty horrific case.”

‘He was peaceful’

Huffman drove two and a half hours from the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia for the announcement. She remembered seeing her brother leave the house in 1962.

“He had books under his arm, and he was hopeful; he was peaceful,” she said after the announcement. “And out of respect for him, I didn’t ask him details. He could have offered details, but he didn’t.”

The next year, a child was born in the large family, she recalled. “Roger would’ve been back for that.” And he never contacted the family. “He was very close to mother, and he would have told her ‘OK, I’m here and I’m OK.’”

But he hadn’t committed a crime, so he wasn’t actively being sought by the police. “What could we do? We waited year after year.”

During the announcement, Huffman called her brother, “Just a wonderful person, a gentle, gentle person. Very trusting, obviously too trusting.”

Afterward, she said, “He loved children; he loved animals. He was a gentle person.” And she added, “I just can’t thank the police enough. … We didn’t know any of this was going on.”

“There was an initial grief” when she heard the body had been identified, especially when they found out it was a homicide. But having his remains makes a difference.

“It’s a big family, and it’ll be a lovely memorial,” she said.

Their mother died five years ago, Huffman said, but she maintained, “She knows the answers. She’s been with him.”

WTOP’s John Domen contributed to this report.