This is the fourth in the five-part WTOP special report Life on the Farm, an inside look at the not-so-glamorous world of Minor League Baseball. A new story will be published every Friday in July.

ERIE, Pa. — “Whoops.”

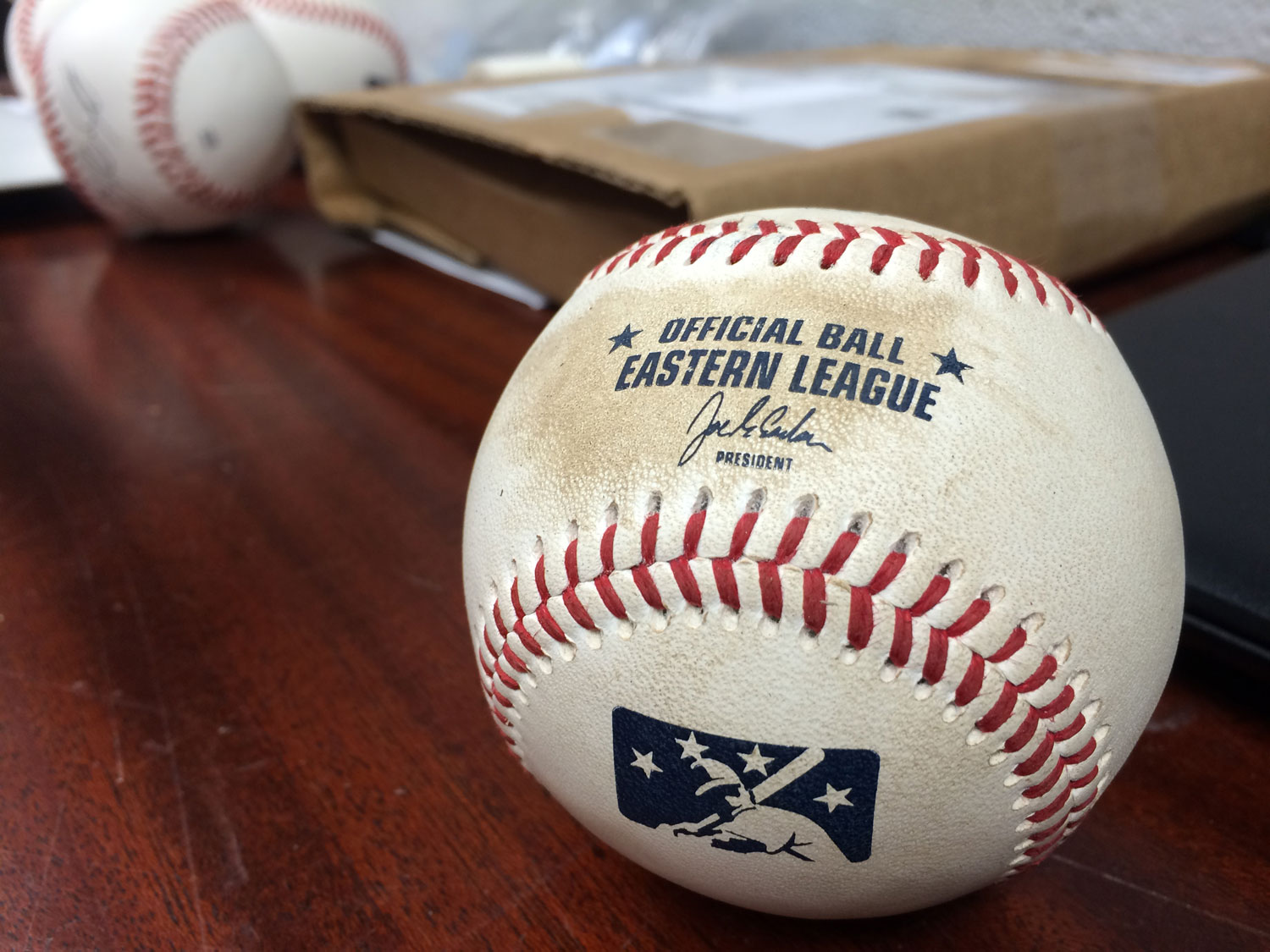

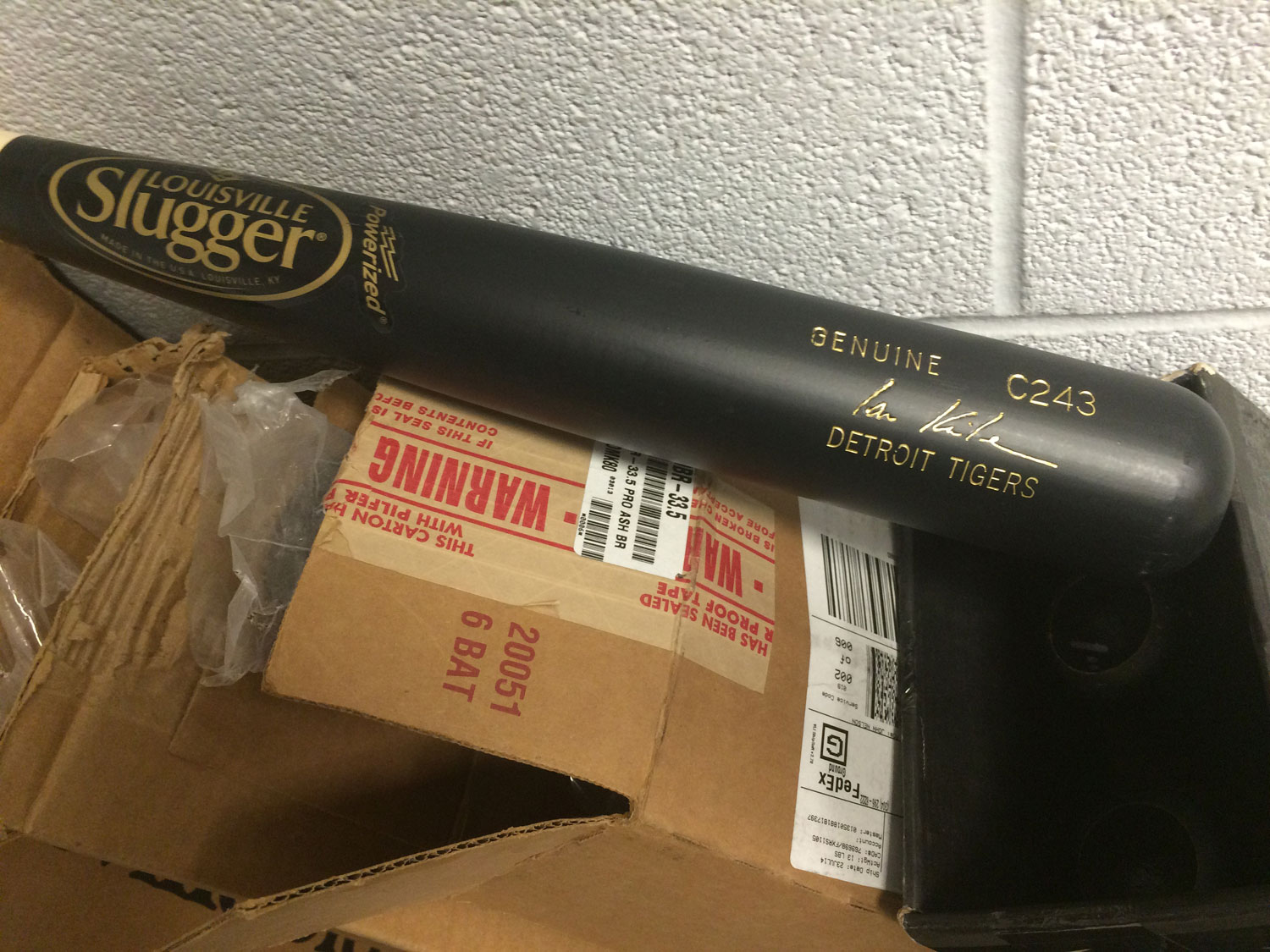

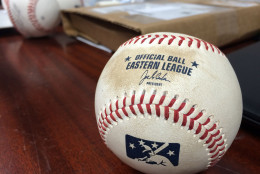

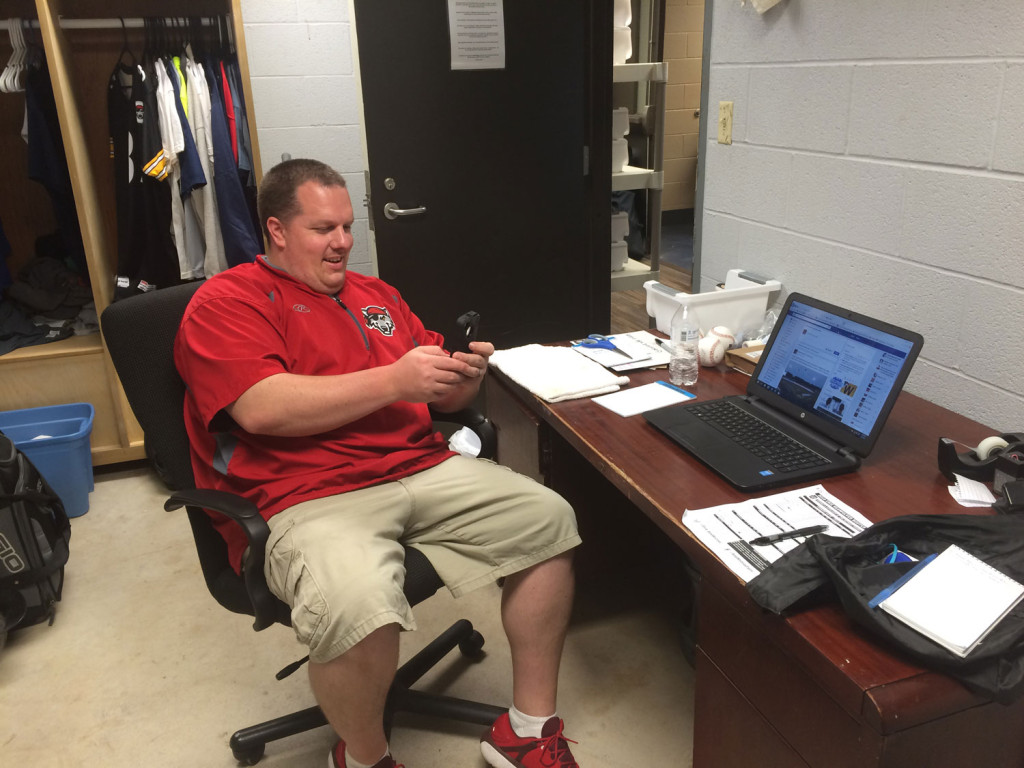

It’s 3:24 p.m. before a 7:05 p.m. scheduled first pitch and Daniel Rose is rubbing baseballs down. It’s a job he’s added to his list of tasks as the home clubhouse manager for the Erie SeaWolves, Double-A affiliate of the Detroit Tigers. As he sits in his windowless, concrete office tucked into the back corner of the home clubhouse at Jerry Uht Park, eight blocks inland off the Presque Isle Bay inlet of Lake Erie, one of the balls has picked up a stain from the mud, right across the label.

It’s the same mud — Lena Blackburn Rubbing Mud — that every major and minor league team uses, the one that gives a game-used ball that grainy feel, as opposed to the slick, polished ones out of the box.

“It’s a manufacturer defect in the material,” Rose says of the stain, explaining that it affects maybe one out of 1,000 baseballs. “You could use it in a game. I won’t.”

He won’t because the splotch could possibly be picked up by the hitter as he sees the rotation of the baseball. That could compromise the integrity of the game. And it would reflect poorly on this part of the job which, like every part of the job, Rose takes seriously.

“My OCD has OCD,” he says.

Rose has been doing this whole clubhouse manager thing for a while. Since his initial stint in Winston-Salem, North Carolina in 2004, he’s spent three seasons in Trenton, New Jersey, three in Fresno, California, a year in Charlotte, and two in Pensacola, Florida. It’s a life nearly as transient and unpredictable as that of the players themselves. And yet, the players rely on the clubbies for many of their basic needs.

The most basic are food and clothing. Rose does all the cooking and laundry for the club, making sure the players are ready to go to work every day. He gets help here and there from the bat boys, but he is basically a staff of one, managing the basic needs of 20 some-odd 20-somethings, probably a handful of future major leaguers among them.

The SeaWolves are Tigers players underneath, literally. The gothic Detroit “D” adorns warmup shirts and shorts, all navy, matching the SeaWolves’ color scheme. All that batting practice gear will head into the industrial washing machine about 10 minutes before the game, as the last players filter out to the field.

Thus begins the cycle of laundry. When the game is over, Rose will do the pants first, so that he can rewash them with the other items to get the dirt and grass stains out. The laundry cycle is a never-ending stream of jerseys, pants and warmups, always needing to be prepared again for the next game in the 142-game season.

“I can do everything in three loads,” Rose says. “You’re fitting 30 pairs of pants and 30 tops in one washer.”

But he doesn’t stitch ripped pants. That duty is contracted out to seamstress in town, who works out of her house, repairing the sliding holes in knees and butts of pants, and usually turns around any fixes in 24 hours. But before you get the idea in your head of some nice, little old grandmother doing all the team’s stitching, Rose is quick to dispel it.

“She’s a profane little old lady,” he laughs. “She would make a sailor blush.”

Rose has learned a lot since that first year in Winston-Salem, where he was the visiting clubhouse manager.

“I was terrible. Horrible. I had no clue what I was doing,” he said. “Talk about throwing somebody to the wolves. Dear God…”

The first team to come in was Myrtle Beach, then an Atlanta Braves affiliate, which included future big leaguers Jeff Francoeur and Brian McCann, who each had two seasons in the minors under their belts already. Rose said they showed him what needed to be done and helped him understand what the job was.

Now, he’s become something of a mentor, not just for the first-year visiting clubhouse manager in Erie — who was supposed to be a ticket intern until unforeseen circumstances thrust him into the role — but to the clubhouse manager community at large.

Rose runs a Facebook page for minor league clubbies. A group without a union, he is something of an unofficial representative, trying to match the best workers with the best positions. When the Erie job came open this year, there was a fair amount of negative chatter around the position, one which had been filled by six different people over the past decade. One reason, as Rose learned, was the basic equipment available.

Some major league stars have opulent incentives in their contracts; a suite in every road city, a personal masseuse, a 900-mile, round-trip limo service for family members. The clubhouse manager’s demands are a little more practical, like the ones Rose detailed to Erie’s management last offseason.

“If you want to get a good clubbie in here, you’re going to have to add another washer and dryer,” he told them.

They did, and suddenly the job became more attractive. Attractive enough to draw Rose himself to it, despite living with his wife and kids in a small Amish village near Fort Wayne, Indiana, 300 miles away.

So what can you expect to make for the pleasure of feeding and laundering a baseball team for the season? Rose said his base pay was $1,500 a month in Fresno, but that many positions are much lower paid, or even without a base salary. Clubbies rely on tips for a good portion of their wages, but it’s important to remember just how little most minor league players make. Base pay for stateside affiliates starts in the $1,100 a month range at the low levels, topping out at $2,800 a month in Triple-A. Players are only paid for the months they are in-season, and their $25 per diem is only paid on the road.

Those kind of numbers mean that Rose renting an apartment is simply unfeasible because of the costs. For the duration of the homestand, he’ll sleep on his manager’s couch, the clubhouse being his actual home.

A few organizations, including the Giants, Yankees and Diamondbacks, employ the clubhouse managers they assign to every level. This allows them better control over standards and practices at all levels of the organization. Most, like the Tigers, have some sort of hybrid system where they employ those at the major league level and at the team’s spring training complex in either Florida or Arizona, out of which a couple of low level minor league teams run. But hiring for the affiliates in the middle, like the Eries of the minor league world, are left to those teams.

Aside from the fact that the Giants kicked in a $1,000 a month housing stipend for Rose when he was in Fresno, he appreciates the idea of a streamlined system run by the big league club to help engender a sense of pride and responsibility in the clubhouse managers across the system. The Yankees even bring all their clubbies in for spring training in Florida.

“You get better retention, better quality of service,” said Rose, who is the Seawolves’ seventh different home clubhouse manager in the past 10 seasons. “You represent something bigger.”

In an age of endless hunts for the next advantage on and off the field, might there be an edge in a streamlined clubhouse environment?

“More information’s out there, seemingly the interest is growing, and everybody’s trying to be exhaustive looking at all angles,” said Dave Littlefield, Tigers vice president of player development, up from Pittsburgh to watch the game.

In a sense, anything and anyone that affects a player and his development — including Rose — is Littlefield’s business, even if he doesn’t technically report to the major league club.

“I think everybody’s looking at the basic business model and realizing that these assets, we want to do whatever we can to help them along the way,” he said. “I think that falls under that category.”

As to whether that means the Tigers and others will follow the Giants and Yankees model is yet to be determined.

“It’ll be interesting to see if that’s the model we all start to move toward or if maybe it’s just a couple of outliers,” he said.

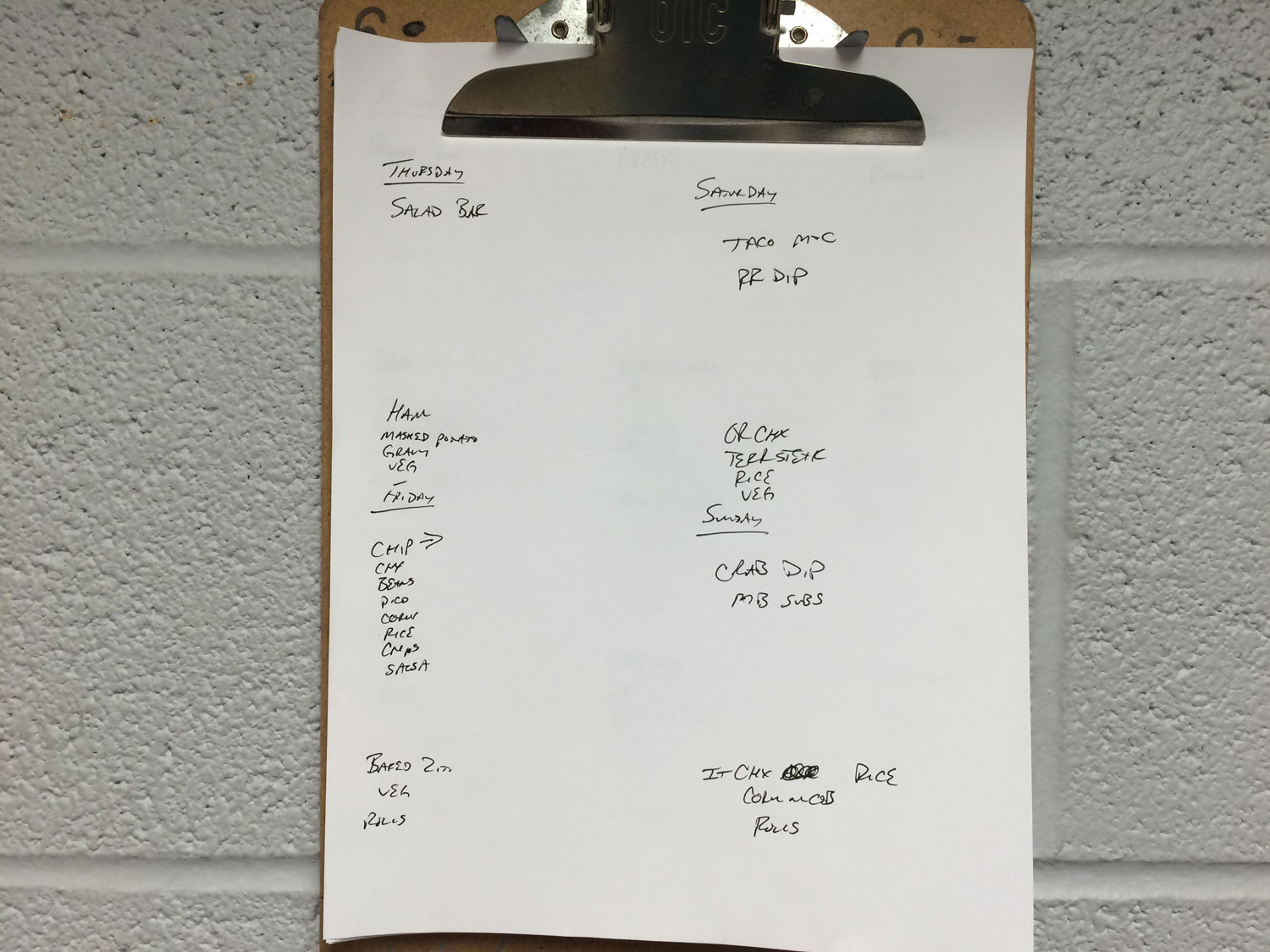

Rose is used to hunting for deals like a coupon clipper. He lives for discoveries like Rhodes Rolls (72 for $4), the kinds of things most of us would never think about.

In Pensacola, on the last day of every homestand, Rose would buy 60 pounds of steamed crawfish, available for just $3 a pound. He would lay out a parfait bar, offering him a chance to unload the rest of the fruit that had been bought before it went bad in the stretch while the team was on the road.

That’s what happens when you’re tasked with feeding an army of growing young men on a budget of $12 per person, per day in clubhouse dues. The Tigers, for their part, toss in an extra $100 a day to keep their players well-fed.

Meals are prepared for 40 people, accounting for the field and training staff, along with the umpires. The team covers laundry costs, and in the case of the Tigers (though not every organization), the gum and sunflower seeds ubiquitous in baseball dugouts at every level.

It’s 4:34 p.m. and Rose is compiling one of the clubhouse’s favorite concoctions, a mix of salsa, cream cheese, green chiles, milk and imitation crab meat. Dips are an easy snack to make for the group, and are something of a specialty for Rose, who has a whole repertoire of about eight different types, one of which he makes each day. Another favorite on the other end of the spectrum is his rocky road dip, with peanut butter, chocolate chips and cream cheese.

Such dishes didn’t fly when he was a part of the Giants organization, though, which instituted strict nutritional guidelines a few years back.

“It was basically, ‘nothing white,’” explains Rose.

No white sauces, such as alfredo. No pasta unless it was whole grain. No white rice. No ranch dressing.

That may sound extreme, but when you win three titles in five years, people are bound to start taking a closer look at your methods.

Littlefield says the Tigers have already invested in a number of off-the-field programs, including sleep and psychological profile studies.

“Clubhouse people put in a lot of work, they’re involved in part of the nutrition offerings,” Littlefield said. “It’s certainly something everybody looks at. And there’s a cost-benefit to all of it.”

Major League clubhouses are full of stories of absurd requests, like the future Hall of Famer who forgot his anniversary and sent the clubbie with $15,000 in cash to Tiffany’s to buy something and get it back to the park in time for that night’s game.

The minors have requests too, but they are usually fairly routine. While Rose and I chat, players drop in and out of his office. One needs three signed baseballs. Another drops off a piece of outgoing mail.

“These guys are really low maintenance,” he said. “They don’t ask for hardly anything.”

That’s not the case with every team he’s worked for. This is, after all, a group of young adults learning how to be grownups while traveling the country in a pack, playing baseball. Sometimes, the learning curve is a little slower.

“One thing I tell the guys at the beginning of the season — any request, as long as they’re legal,” said Rose. “And the reason I have to say that is because I’ve had illegal requests in the past.”

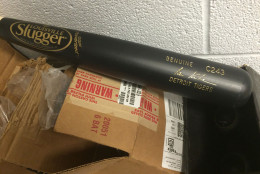

There are other duties. Two SeaWolves suffered nasty facial injuries in a three-game span earlier this year, one after breaking his nose bunting a ball into the plate and back into his face, the other who couldn’t react in time to avoid a fastball. Each needed a helmet with an added protective flap, a feature that doesn’t come standard issue.

“We had to get special helmets made for them and get them quick,” Rose said.

That meant working in conjunction with Detroit and Rawlings, then expediting shipping,

But the most common request is just shipping, even mailing letters.

“There’s no way for them to get to a post office, mainly because only about half of them have vehicles here.”

Perhaps Rose’s most unique request came from 2014 World Series MVP Madison Bumgarner, back when he was in Triple-A. Like Rose, Bumgarner is a North Carolina native and loves Sun Drop, a regional soft drink comparable to Mountain Dew not sold on the West Coast. Bumgarner knew Rose was flying home one week while the team was hitting the road, so he gave him $100 cash with a simple order.

“Make two cases of Sun Drop your luggage on the plane back.”

Rose taped two 30-packs together, stuffed them in a suitcase and ponied up the $25 bag fee to bring the star prospect a taste of home.

At 5:02 p.m., relief pitcher Josh Turley pops his head into Rose’s office with a pressing request of his own.

“Do you have the key for the ping pong room?”

The game itself offers the most downtime of Rose’s day. He’s preparing the postgame spread, but he’s also got enough time to get caught up on other affairs, including using FaceTime with his wife and kids back in Indiana in the eighth inning to tell them goodnight.

Ideally, the bus leaves 45 minutes after the last pitch of the game. This is a tough turnaround for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the fact that “last pitch” is a moving target, one which changes every game and is never certain until after it happens.

This night, the target is even harder to pin down, because the clubbie’s worst nightmare has struck. The SeaWolves strand the potential winning run at second in the bottom of the ninth of a 2-2 game. We’re headed to extra innings.

The biggest concern isn’t how late the night will stretch, but how to keep the food ready and hot without either overcooking it or having it sit out and give the entire squad food poisoning.

In the top of the 10th, Akron DH Mike Papi drives an RBI triple off the center field wall. Rose pops out of his chair and starts putting plates together. By the time Ivan Castillo’s sacrifice fly plates Papi to put the RubberDucks up 4-2, he’s already made the umpires’ meals. As fans stream for the exits, Rose kicks his routine into full gear.

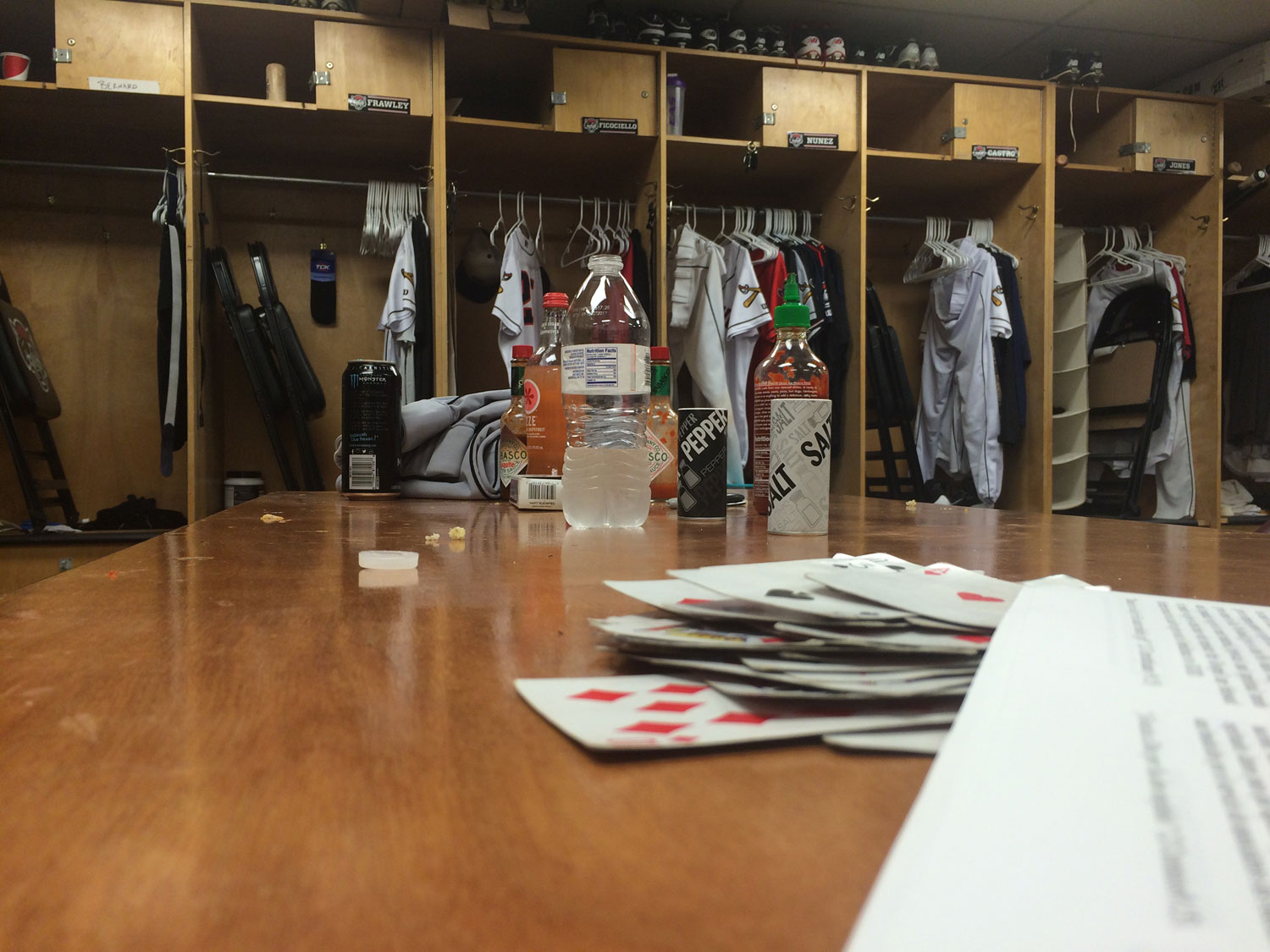

At 10:27 p.m., when the last out of the bottom of the 10th is made, the clock officially begins. The chicken is out of the oven and onto the white plastic tables running across the middle of the room before the relievers arrive from the bullpen and pop open the clubhouse door.

There’s an awkward quiet that punctuates every post-loss clubhouse. Some of it is genuine anger, some of it is performative; all of it is accentuated by the lack of music that accompanies victories. But there’s no time to sulk tonight. Players grab mitts, water bottles and personal effects from their lockers and start stuffing them in duffel bags for the bus. The only sounds are functional ones —creaks and shunts of cupboards opening and closing, clinks of belts unbuckling, the soft, swooping parachuting of clothes landing in their respective piles, ready for the next wash.

“It’s always easier after a win,” Rose whispers as he ducks back into the laundry room. “I hate the quiet.”

There’s no white board, as there often is in the big leagues, with a bus departure time. The players know the drill by Double-A. The earlier they get on the road, the earlier the six-hour countdown until they arrive at the hotel in Harrisburg — with real beds — begins.

Fireworks pop off outside. As is almost always the case, the show will go unseen by the players. The finale sounds like a firefight, rapid explosions in quick sequence. At 10:52, it’s over, and nobody seems to have noticed.

“Running total, right?” asks a player just out of view.

Rose tries to keep bookkeeping as simple as possible for his players, managing a season-long total of the dues they’ve paid. He might get anywhere from $1 to $20 in tips per homestand, per player, dependent on a lot of different factors. But making things easy at a time like this, when they are rushing to get to the bus, can’t hurt.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that Rose said his biggest tip came from longtime MLB player and current MLB Network analyst Mark DeRosa while he was on rehab assignment with the Giants. Just as players can look forward to a break from the standard clubhouse fare with a catered meal when a star player is on rehab, so can the clubbies, who get a night off cooking duty. But with Triple-A Toledo much closer to Detroit than Erie, this is not a rehab destination.

It’s 11:05 p.m. and Rose is running back and forth between his office and kitchen as a line builds to pay up on dues. Players snag granola bars, wash down a couple Advil with a swig from something from the non-soda machine just outside Rose’s office door before heading to the bus.

The door closes behind the last player at 11:19 p.m., but stragglers keep popping back in hurriedly over the next couple minutes to grab random items like a yogurt to go, or a pile of cards, quickly counted to ensure a full deck for the ride.

What looked like an evacuation 10 minutes earlier is eerily silent. Rose’s day has another couple hours of vacuuming and laundry, of taking the trash out. He’ll make the call whether to head home right away or crash on the skipper’s couch and make the drive in the morning once he’s done.

As he drives west along Interstate 90, along the south slope of Lake Erie, through Cleveland and northern Ohio, he’ll come to a split in the road in Toledo, home of the Tigers’ Triple-A affiliate. For now, he’ll turn left down Highway 24, and follow the road home. Someday, perhaps, he’ll turn right, up Highway 75, to Detroit.

Part I: The road well-traveled

Part III: Minor league Moneyball

Part V: The unwitting translator