ARLINGTON, Va. — “Life is short, but it’s very wide.”

That’s a statement with layers coming from one of the tallest and most slender men many of us will ever lay eyes upon. But it’s a sentiment that perfectly embodies the life of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, whose influence in modern American culture is as broad as his 7-foot-2 frame is high.

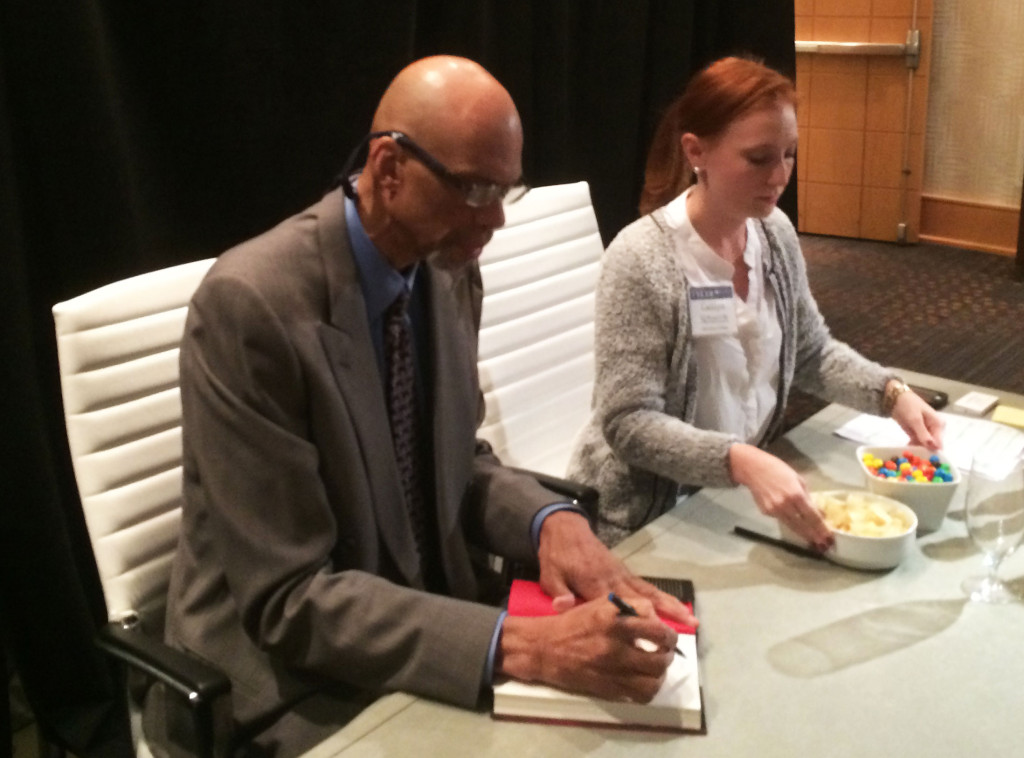

Abdul-Jabbar was interviewed last week by the Director of the Mercatus Center at George Mason, Tyler Cowen, a professor of economics who conducts one-on-one interviews such as these as part of a series of talks. For those who only know Abdul-Jabbar as a basketball player, this may seem a surprise setting. But at this point in the 68-year-old’s life, Abdul-Jabbar, who was labeled as an “NBA All-Star, author, activist” on the program, might well identify with those characterizations in reverse order.

The talk was wide-ranging, bouncing from social issues, to Abdul-Jabbar’s writing, to basketball and his love of jazz. After all, not many people can say they led the league in scoring, had their writing featured in Time Magazine, appeared in a major motion picture and was a regular at Thelonious Monk shows at the Village Vanguard in Greenwich Village.

Someone who, when asked about his heroes, lists Jackie Robinson, Joe Louis and Wild Bill Hickok as the first three out of his mouth.

Someone who, when describing the wide variance in famous jazz musician Sun Ra’s various live performances as “the difference between cubism and Renoir.”

So what can we learn now from such a worldly citizen, a UCLA graduate who spends his time writing books about Sherlock Holmes’ older brother, Mycroft?

Born Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor, Jr., Abdul-Jabbar changed his name upon converting to Islam, which puts him at a particularly interesting intersection of the issues facing America today. As a self-made black American Muslim in the wake of recent racial clashes and the divisive bluster of certain presidential candidates, he’s had plenty to say.

Any Washingtonian who didn’t already know about Abdul-Jabbar’s second professional life as a writer and activist needed only pick up The Washington Post Monday, in which the Hall of Famer called upon Republican primary voters supporting Donald Trump to examine their reasons for voting for him.

But he is also still, at heart, a basketball player.

Kareem doesn’t like the three-pointer. He believes it to be the reason nobody uses the skyhook anymore, the shot he forged a Hall of Fame career from.

“So the kids, they don’t want two points,” he says. “They don’t want to work with their back to the basket. That’s not cool. They want to go out there in the stratosphere.”

He doesn’t see it as a progression of the game — though he admits to Stephen Curry’s brilliance, citing the specific example of him hitting 77 consecutive threes in practice one day — but rather as a shortcut from the process, from the time required to learn low-post footwork, and one that overlooks what he sees as an obvious truth.

“They don’t get to realize that if you get close to the basket, a lot more of your shots will go in.”

Abdul-Jabbar revealed that he had worked with both Joakim Noah on his defense and tried to teach him the skyhook (“he wasn’t interested”), and that he worked for a while with Andrew Bynum up until he landed his $58 million contract from the Lakers.

“At that point, Andrew thought that I didn’t know anything anymore and that he didn’t have to listen to me.”

After being selected with the 10th overall pick in the 2005 NBA Draft at age 18, Bynum was highly regarded, but never developed into the superstar many thought he would be. He eventually left L.A., landing in Cleveland in 2013, then for two games in Indiana, the last time he wore an NBA uniform coming the day after Christmas that year.

Abdul-Jabbar spoke with disappointment and regret about Bynum, but with more impassioned fire about how to address the larger issue of student-athletes and the NCAA. The first question he fielded from the crowd on hand was about whether or not student-athletes should be paid, and he was unequivocal in not simply his personal beliefs, but the direction he believes we are headed.

“I definitely think NCAA athletes should be paid (and) I think it will happen,” Abdul-Jabbar said, recalling how not only was he not compensated during his time in college, but not even allowed to work, as a scholarship student or band member would be.

“There’s a way that they can be equitable about paying the athletes. Taking what they take by providing a platform, but I think the athletes should be paid … I think they should think about a way to not exploit the athletes and give them the opportunity to be comfortable while they go to college.”

Pushed further about the specifics of the one-and-done rule, the NBA’s current system that prevents high school graduates from being drafted into the NBA until they reach 19 years of age, Abdul-Jabbar was clear that he disliked it, but for interesting reasons.

“The one‑and‑done rule stinks,” he said. “It’s bad for the game of basketball in college, because all the talent doesn’t stay there. It’s bad for the pro game, because the guys coming out of college that have done one‑and‑done are arrogant and think that they are prima donnas.”

Instead of doing away with the rule, though, Abdul-Jabbar is in favor of raising the age further, to 21, which would potentially make the system closer to Major League Baseball’s. Obviously when dovetailed with a plan to pay college student-athletes a stipend, the intent would be to encourage them to actually get an education, rather than simply count the days to a potential seven- or eight-figure paycheck.

And when one understands Abdul-Jabbar, his history and his motivations, that desire to see young men, especially of color, get an education makes a world of sense. His head coach at UCLA, the legendary John Wooden, graduated 95 percent of his players, well above the general student population. Abdul-Jabbar believes, first and foremost, that educational opportunities will lead to economic and social equality for future generations, and believes in putting in the hard work — whether on footwork in the paint or by reading in the library — to get there.

“I don’t think the soft expectations have benefited minority communities very well,” Abdul-Jabbar says. “I think we still suffer from that. A lot of people seen to be able to accept it and understand it because they know how terrible our public school systems are and how they have failed, in many cases, to educate the students in their districts.”

So he encourages others do to what he has done with his life, to not merely settle for being what people expect of him, but to strive to absorb as much knowledge as they can.

“I just try to tell people that knowledge is power. You’ve got to accumulate as much power as you can. That requires that you go to the library and that you read and experience life in ways that enable you to use that power.”