Rick Massimo, wtop.com

BETHESDA, Md. – In a small room within the sprawling Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, veterans from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are immersed in what looks like a video game, complete with a hand-held controller and virtual- reality goggles.

It may look like the newest version of Call of Duty, but it’s the latest technology in the fight against post-traumatic stress disorder.

It’s called Virtual Iraq, and it puts patients back in the war zones they left behind, complete with the smells and vibrations of their experiences at war in the Middle East.

At the National Intrepid Center of Excellence, therapists use Virtual Iraq to help veterans acclimate to the stress their own memories can cause.

Dr. Michael Roy, of the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at the Uniformed Services University, runs the trials for the virtual-reality therapy. The program was developed in 2004, and Roy, a retired Army colonel, began using it with patients in 2007.

With the goggles on, the patient relives his or her experiences from wartime in real time. The wearer is placed in situations such as inside a Humvee, driving through mountains, walking through a town square and other backdrops — whatever matches the events that haunt the patient. They describe the setting and the happenings to the therapist, who adds and changes events such as “chopper flyover,” “IED” and more.

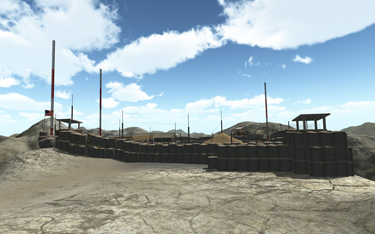

A look inside the world of Virtual Iraq:

The goal is to re-create the moments that led to the patient’s condition, and to duplicate the stress that the veteran felt during their combat experience.

Roy says there are two goals: to “habituate” the patient to the stress, so that common events don’t trigger bad memories; and to open the gateway to conversation.

One of the key symptoms of PTSD, Roy says, is “a desire to avoid any reminders of the trauma.”

“People with PTSD, they don’t let down — and they avoid,” he says.

When the memories are racing and the stress is elevated, that’s the time to talk about them, Roy says. But it’s hard to re-create that stress and that moment if the patient is avoiding it.

“We’re putting it in your face. You just want enough to get them reacting, get them talking, get them feeling,” Roy says.

Traditional therapy, called imaginal therapy, asks the patient to describe their traumatic experience in as much detail as possible, Roy explains. But that can be a problem.

“Somebody who wants to avoid thinking about anything associated with that experience, that’s really hard to do,” Roy says.

Virtual reality “kind of takes the weight off their shoulders, because it’s providing reminders,” Roy says.

He adds that the therapy is “appealing to [veterans], especially younger folks who are used to playing video games.”

␎

The Virtual Iraq program has a variety of background settings in order to duplicate a patient’s memories. (Photo courtesy USC-ICT)

Skip Rizzo, a clinical psychologist from the University of Southern California, developed Virtual Iraq with colleagues from the university’s Institute of Creative Technologies by adapting the video game Full Spectrum Warrior, which itself is an adaptation of a video training application from the Department of Defense.

Roy had been looking for a way to use virtual reality to treat PTSD since the 1990s. The technology at the time was too primitive, so he cobbled together a montage of combat scenes from Hollywood films such as “The Deer Hunter” and “Saving Private Ryan” to show patients while they were simultaneously running on treadmills and solving math problems.

“It actually worked pretty well” in raising patients’ stress levels, Roy says, but as the technology improved, so have the results.

Another researcher has found that the therapy worked well for people who didn’t take to imaginal therapy, but Roy says that even in that trial, more than half dropped out.

“I don’t think it’ll ever be for everybody,” Roy says, but “a niche or a subset” of patients will be helped by it.

So far, the results have been encouraging. Roy can point to brain scan results that show the therapy has helped to quiet the areas of the brain that activate in PTSD patients.

He has stories of individual success.

“We had one patient who was reluctant to use the subway, go to a restaurant or the movies,” Roy says. “Just a lot of avoidant behavior.”

After going through the therapy, Roy beams, “he actually went to the Army-Navy football game, with 60,000 people, cannons being fired and so forth.”

A nurse anesthetist who had been unable to work in the operating room since a mortar attack in Iraq “was able to return to her job.”

The therapists who work hands-on with the technology have similar stories.

Nurse Denece Clayborne sees patients from the beginning of the study to the end, and says “A lot of the service members have tried a lot of other therapies, and they end up trying this… They find it more useful.”

␎

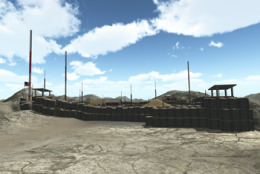

The point of Virtual Iraq is twofold: To acclimate patients to traumatic stress and to get them to open up. (Photo courtesy USC-ICT)

Research psychophysiologist Michelle Costanzo says that some patients were “like a different person” after the therapy. “They’re often a lot warmer, and they’re smiling.”

Therapy includes a couple of sessions of what Roy calls “setting the base” — learning veterans’ stories, teaching relaxation techniques and helping them recognize the problem. Then they enter Virtual Iraq.

The first thing you notice about the program is the graphics — they’re surprisingly low-tech. Clayborne agrees, but adds that “it’s enough to trigger certain memories.” What the program lacks in visual realism, she says, it makes up for in the other senses, particularly the sounds, vibrations and smells (which include cordite, body odor, burning trash and more).

“The therapist will guide them through reliving the event,” Costanzo says.

They’ve got a grim menu of choices in order to help tailor the patient’s virtual experience to match his or her memories – “IED,” “Flip Humvee” and “Burning Trash” are among the options.

Through the re-creation of a traumatic event, such as an injury or the death of a buddy, patients can experience not only “habituation” but what Costanzo calls “processing.” For example, a patient may anguish over having turned a vehicle to the left when he should have turned right, but with a detailed account of the event, a therapist can ask, “Did you have that option?”

She says patients can learn that “there’s only so much control we have.”

Virtual Iraq is available in many V.A. facilities; the Air Force has it in all its treatment facilities. But not everyone uses it.

“We’re making inroads,” says Roy, who add that there’s still a resistance among some doctors that Roy calls generational.

“Doctors tend to use the same medicines as they used in medical school; it’s hard to get them to change. We have to educate them when they’re in medical school and residency training.”

Roy’s group is also trying to generate more awareness of the therapy in the patient population, so they can see that it’s an option. They use Twitter and Facebook to attract veterans to their website, and go to veterans’ gatherings such as Yellow Ribbon and Wounded Warrior meetings for returning veterans.

The hope is that, while it may seem counterintuitive to return in one’s mind to a scene of crippling horror, veterans will learn that that’s the best way to move on.

“Reliving that,” Clayborne says, “will enable them to get past it.”

MC2 Brittney Cannady tries out Virtual Iraq:

Follow @WTOP on Twitter.